Contemporary western Monster Studies posit that a protagonist with whom we identify will be the threatened center of the tale, while the monster will be the outside “other.” Theory tells us that such beings are hybrids. Like us, but not, in their fun house mirroring, we see our divided spiritual possibilities. Monsters are us writ large, replete with mythic perceptions and cultural projections.1

Some ideas of otherness apply to Southeast Asian figures. Some are born monsters (with physical differences: hermaphrodites, giants, albinos, etc.); some monsters are made (pontianak, women dead in childbirth); and still others self-generated (Rangda and Barong Ket,2 discussed here). However these last figures differ from western patterns. Due to Balinese correlation of microcosm (self) and macrocosm (cosmos), the “other/hybrid/monster” is never really “outsider” but integral to individual and cosmic wholeness.

The best known Balinese story, related to these figures and their masks, begins as a standard western tale, with heroic/human (Baradah) confronting a terrible sorceress (Calonarang), but soon both the hero and attacking Calonarang become “other.” Baradah becomes the protective lion body puppet (Barong Ket, also called Banaspati Raja, “Lord of the Forest”) and Calonarang the demonic widow-witch/goddess Rangda (literally, “widow”).3 The names connote the masks they transform into (which can be different characters in varied stories). Both are monster-like hybrids. The masks give divine power material form. Barong and Rangda exemplify the rwa bhineda (“two in opposition”), the yin-yang that grounds Balinese being in the world. Since intellectually the two principles are inseparable, they imply a Balinese understanding that the “other” is really part of the self. The destructive is inherent in being.

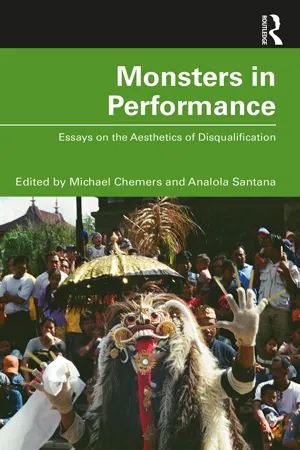

In normal western narratives, the negative monster (comparable to the tusked and fanged4 Rangda mask) will have victims – an expendable child or unwary bystander – but not defeat the protagonist of the story (here Mpu Baradah, who transforms into the Barong Ket). It is the human protagonist in a western narrative who stems the suffering. But, in Balinese performance, the protective Barong retires and instead the monstrous Rangda finalizes a ritual curing of the community. Her danger always returns, as she brings death and plague, but also life and blessings (see cover of book for image of Rangda).

Like all good monsters, Rangda looms large. She is a transformation of the human leyak (witch). Calonarang (calon means “candidate,” arang is “incense”) is, in the best known narrative, a widowed queen who transforms into the tusked mask of Rangda, infused with the power of Hindu Goddess Durga, co-creator of the world in Bali’s creation story, Purwaka Bhumi. Her consort-opponent is Siwa (India’s Shiva), identified with Barong Ket. The monsters are also gods.

Neither Rangda nor Barong fit patterns of the divine in a Semitic-Christian world. The West wants its god all-good and women do not qualify. What is more, antagonists like Satan and Eve are rebels who bring on suffering and instigate evil. In the Christian paradigm the divine is exonerated from anything negative, and demons and women deviate from divine plan.

Balinese Hinduism posits a different genesis – gods (dewa) and demons (buta kala) are subsumed in a divine unity in which positive and negative are not always separated. Evil as well as good comes from the fact of material creation, which includes sickness and destruction. Humans are a part of ongoing cycles of generation and degeneration in a world where destruction can be impersonal – a sensible cosmology in island Southeast Asia where extreme vulcanism, earthquakes, typhoons, and tsunami abound. Both the dewa and the kala are supernaturals and must be balanced. The requirements (offerings, prayers, rituals, performances) may be different for the peaceful divinity than the unruly demon, but the outcome of honoring will be identical – calm in tribuana (“three worlds” – i.e. heaven, earth, underworld). The human is engaged in a balancing act in which cosmic good and evil are intermixed. Sakti (spiritual power) is ungendered, neither good nor evil – it just is – humans manipulate it to achieve the balance (Anderson 1972). Performance that honors Rangda is an offering that lets her demonic force appear and be “fed” with offerings, music, and dance. Humans acknowledge and give form to destructive tendencies via the apotropaic masks of Rangda and Barong so these powers protect rather than destroy. If you allow the demons (inner and outer) to appear in the contained space of performance, you prevent them from running amok in daily life.

The discussion will proceed in three sections: first, description of a calonarang performance; second, selected interpretations of the Calonarang character; and third, concepts of purification.5

Performance6

In June 2003 Bali was in recovery from the October 12, 2002 bombing by Islamic fundamentalists of the Jemiah Islamiyah at Kuta Beach, killing 202, including 88 Australians plus other foreigners. Soon Osama bin Laden released a tape telling Australians: “You will be killed just as you kill, and will be bombed just as you bomb” (Fisk 2002), stating the bombing was payback for Australian support of the 2001 American intervention in Afghanistan. Bali as a Hindu-Buddhist island was targeted by Indonesian Islamists sympathetic with Saudi influenced pro-Taliban groups. Kuta Beach with its bars and bikinis was filled with kafirs (infidels, non-Muslims) – Balinese Hindus and westerner tourists. Kuta represented, for attackers, a monster to be destroyed.

I was doing research on arts after the Bali Bomb. The blast caused tourists to vanish, bringing severe economic downturn. Recession inspired the Ajeg Bali (Strong Bali) movement (see Allen and Palermo 2005; Picard 2008) with its island-wide pledge of “we will survive.” This fueled an upswing in ritual performances. Some felt spiritual deficiency had allowed the forces of darkness to prey.

I was working with I Nyoman Sedana and I Ketut Kodi, translating a topeng (mask) performance done as a healing rite.7 Dance ethnologist Rucina Ballinger invited me to a calonarang near Ubud, put on by the local village troupe for kanjeng kliwon, a period every 15 days when spirits abound and Siwa and Durga (principals in the Calonarang myth) receive offerings.8 The villagers gathered around a rectangular performance space next to the pura dalem (chthonic temple), across from the cemetery. A small, curtained pavilion set on three-meter stilts in the left corner had a plank to descend. This enclosure served as a perch for the Rangda mask performer. The all-male performance was close to descriptions by 1930s researchers (Belo 1966 [1949]; de Zoete and Spies 2002 [1938]; Covarrubias [1937]).

Calonarang first appeared as an old woman (played by a man), leaning on her staff as her young disciples did a mandala-spaced dance connoting the directional points as homage to Durga. Next a man playing a village woman gave birth assisted by farcical companions. The semi-comic demon Celuluk9 with grossly enlarged head, breasts, fangs, and wide steps, lurked with monkey assistants and stole the baby/doll for Calonarang’s sorcery rites. The corpse (watangan, bangke), a local youth trained by his guru to withstand psychic annihilation, was carried in by four men. The young man, after three days of fasting, had been wrapped in a shroud and gone through customary funeral rites. This participant (sometimes said to stop breathing) was delivered to the cemetery to remain alone until the end. He (and now, sometimes she [Suyatra 2019]) is thought to be especially vulnerable to battle of right-handed (tengan) magic of the ceremony‘s protector (called the tukang undang or “inviter”) vs. left-handed (kiwa) magic of local leyak (sorcerers), believed to infiltrate the audience to “eat” (psychically attack) the corpse (Wirawan 2019; Suyatra 2017, 2019). The white-clad tukang undangs welcomed any local leyak to try his power (a high point of tension). Should the event go amiss for the watangan or others, the leyaks win. Recent newspaper accounts report increasing spectacle regarding the watangan, including actual burials and/or minutes-long cremations.10 It is not easy being the corpse.

The comic panasar (clowns) improvised dialogue in colloquial Balinese telling that Kediri kingdom’s capital, Daha, was in an epidemic caused by Walunatang Dirah (Queen of Dirah [also Girah, Jirah]): the clowns additionally translated the obscure Kawi (Old Javanese) of the major character’s dialogue into colloquial Balinese. Mpu Baradah (a strong male character type) and priest to King Airlangga of Kediri appeared with his student Bahula, who had married Calonarang’s daughter, Ratna Mangali. Soon Bahula convinced his wife to steal Calonarang’s book of magic, Lipyakara, bringing on the resolution.11

Calonarang transformed into Rangda (presented by a second performer with the elaborate costume and tusked mask) and Rangda soon descended from the raised p...