![]()

Chapter 1

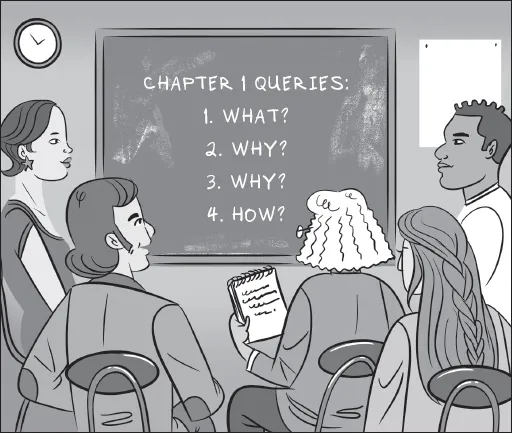

Assessment Literacy: The What, the Why, and the How

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

This is a book about educational testing, written specifically for the classroom teachers and school and district administrators who keep our schools running. In this very first chapter, I'll tell you what the book is about—and why the topics it treats are so important to me, to you, to your colleagues, and to the entire nation.

As many teachers and administrators did, I chose a career in education because I wanted to help young people learn—individual children, of course, but also children collectively. Although a high-quality education for the individual child is the ultimate goal of schooling, folks who are ambitiously minded think in more macro terms. What we want is a high-quality education for every child. If we are practical as well as ambitious, we try to figure out how to make that a reality. Now, after a lengthy career, I am convinced that the single most cost-effective way to improve our nation's schools is to increase educators' assessment literacy.

I suspect that my "most cost-effective" improvement claim might strike you as overstated, but I really think it is stone-cold accurate. To illustrate, if we were somehow able to double the salaries of those in the teaching profession, we would soon find flocks of talented young men and women signing up to become teachers; in time, those talented new teachers would have a positive impact on students' learning. Yet, doubling teachers' salaries would cost a nontrivial chunk of change. Similarly, if we could reduce by half the number of students that each teacher must instruct, the resultant smaller class sizes would likely lead to learning improvements. But, as was true with my salary-doubling fantasy, any meaningfully reduced class-size strategy would be expensive—probably prohibitively so.

It is because cost constraints often deter us from taking powerful actions to improve education that I believe a book touting a truly cost-effective strategy to improve our schools deserves attention. Increasing assessment literacy is just such a strategy. It requires no state budget-busting revision of school funding formulas; it only requires educators to learn something new. When assessment-literate educators make educational decisions based on appropriate assessment-elicited evidence, the resultant decisions will almost always be more defensible—meaning, more likely to improve students' learning.

That's why the content of this book matters to me, and why I think it should matter to you and to all of us.

Before we dig in deeper, I want to pause for questions. Specifically, here at the outset I want to explore four questions in a way that will provide a framework for the entire book:

- What is assessment literacy?

- Why aren't educators already assessment literate?

- Why should educators become assessment literate?

- How can an educator become assessment literate?

By the close of this chapter, I hope that you'll have arrived at your own answers to these four questions. Oh, to be sure, I hope your answers will resemble mine, but modest differences are certainly tolerable.

What Is Assessment Literacy?

Here is the definition of assessment literacy that I've been ladling out in my writing for the past two decades:

Assessment literacy consists of an individual's understanding of the fundamental assessment concepts and procedures deemed likely to influence educational decisions.

Because this whole book revolves around the concept of assessment literacy, let's make sure we agree on what the key components of this definition mean.

Which Fundamental Assessment Concepts?

First off, you'll note that the definition centers on an individual's "understandings of fundamental assessment concepts and procedures." What are these fundamentals, anyway?

Well, for openers, we can look at a pivotal term in that phrase: assessment. In this book, I'll be following the lead of most educators today who use the terms assessment, test, exam, and measurement interchangeably. Yes, a few writers attempt to squeeze some subtle distinctions from certain of those labels, but I typically don't. For many adults, of course, the term test evokes an image of the paper-and-pencil exams that they were obliged to complete when they were students themselves. Then, too, the label "measurement" often conjures up images of determining distances (from short ones to interstellar ones) or calculating weight (from slight to substantial). Perhaps the avoidance of such preconceptions is why the label "assessment" currently sits atop today's testing-synonyms usage rankings. It is seen to be the most generally applicable descriptor, and it is accompanied by less extraneous or contaminating baggage.

Educational assessment, then, can be used to describe the full range of procedures that we employ to determine a student's status—for instance, how well students can wander in the world of algebra or how skillfully a student can slug it out with science concepts. In the pages to come, if you occasionally find me using the terms measurement, exam, or test rather than assessment, please know that I am not trying to nudge you toward some sort of cleverly nuanced assessment truth. It's more likely that I simply became tired of using the A-word.

But what about the L-word? Assessment literacy is less akin to "literacy" in general—the ability to read and write—than it is to competence and knowledge in a specific arena, such as "wine literacy" or "automotive literacy" or "media literacy." As stated in the definition presented just a few paragraphs ago, the basics of assessment literacy are fundamental assessment concepts and procedures—those that are truly foundational. In this setting, concepts refer to such measurement notions as validity, reliability, and fairness. Procedures refer to the techniques or methods commonly used to build or evaluate tests—for instance, the techniques employed to identify test items that are biased against certain subgroups of test-takers.

Decision-Influencers Only

As you can see, assessment literacy is not centered on just any old run-of-the-mill collection of fundamental concepts and procedures; it deals exclusively with the handful of fundamental concepts and procedures likely to have an actual impact on educational decisions that can change children's lives.

Although the stakes are high, an encouraging feature of assessment literacy is that it focuses on just the decision-influencing basics of educational measurement. Grasping these is an eminently manageable task.

Why Aren't Educators Already Assessment Literate?

After this little bit of delving into the nature of assessment literacy, you might be wondering about the degree to which today's educators are familiar with the concepts and procedures of educational assessment you'll be reading about in the pages to come.

It is a good wonder, and it's a suitably timed wonder for this first chapter. Sadly, an enormous number of today's educators are not assessment literate. They simply do not understand the fundamental concepts and procedures of educational testing.

Assessment Literacy Initiatives

I'm not the first person to point this out. Governmental groups such as state departments of education and nongovernmental organizations including the National PTA and the National Association of Elementary School Principals (NAESP) have launched numerous initiatives directed toward enhancing the assessment literacy of educators, educational policymakers, students' parents, and even students themselves. But most of those efforts have only been undertaken in recent years, so we are unlikely to see a substantial boost in assessment literacy among these targeted groups any time soon.

At present, many observers conclude that the target audiences most in need of enhanced assessment literacy are the nation's teachers and educational administrators. The more knowledgeable that these pivotal people are about educational testing's basics, the more readily they can share their assessment-related insights with other individuals, such as the school board members who govern our schools or the parents of the students our schools serve.

It has often been said that "a little knowledge is a dangerous thing." As with most such maxims, at least a wisp of wisdom resides therein. When people know a little bit about something, they frequently believe they know more about it than they actually do. Thinking they've acquired all they need to know, they're disinclined to pursue the topic further and, thus, are all too ready to proffer advice well beyond what they should be proffering.

Far too many of our nation's educators are caught in this trap of knowing too little about assessment yet believing it's enough. These are professionals, and many have been so for years. They write tests, formal and informal. They administer tests regularly, both tests of their own design and tests provided by external, expert sources. They look at test results and make decisions about what these results mean. It's all going fine. What could they be missing? What more is there to know?

Problems in the Midst of Progress

We are now beginning to see a meaningful uptick in the number of states that require teachers to complete a formal course in educational measurement during their teacher-education days. Yet, and this is a yet well deserving of its italicization, many of these teacher-preparation courses are taught by professors who are measurement specialists. The courses they design are filled with debatably relevant, sometimes-obscure assessment content. Where they ought to be serving up only the most decision-influencing content, they swamp prospective teachers with impractical measurement esoterica. Putting it candidly, at present we can't automatically conclude that a newly minted teacher, even one with an educational measurement course under his or her belt, is actually assessment literate.

Nor are educational administrators immune from the adverse consequences of assessment illiteracy. In many locales, most of the individuals who have completed training to become certificated educational administrators were not required to take even a single course in educational assessment. And if they were, there's a high likelihood that the course they completed was more in line with the technical interests of the measurement maven who taught the course than with the practicalities of how real-world educators should measure the progress of real-world students.

What I am contending here, then, is that it is a profound mistake to assume that the teachers or administrators with whom you interact are, themselves, assessment literate. They may indeed, through no fault of their own, be ill-prepared to make many of the most important instructional decisions they face. They think they know "enough" about assessment, but most of them don't.

An Author's Confession

And just so you don't think I'm using this printed-page platform to belittle my colleagues, I am putting myself right up there near the head of the "He Thought He Knew" queue. You see, when I was preparing to become a high school teacher, I never received any meaningful instruction regarding the fundamentals of educational measurement. Exactly three class-sessions of a required educational psychology course I took were devoted to the care and feeding of multiple-choice test items, but this was all that I and my fellow teachers-to-be got.

Thus, when I began teaching my first students, what I drew on to devise my own classroom tests was my recollection of the tests that I had personally taken as a student. Some of those tests were solid; some were shabby. For fully the first half of my career as an educator, I really had nothing to do with educational testing, preferring instead to focus on the instructional side of teaching. Like most, I assumed that I knew "enough" about testing, and that loftier levels of understanding were the provenance of measurement specialists, psychometricians specifically trained to successfully wrestle assessment problems into submission.

It was only when test scores began being used to make high-stakes decisions about students and schools—often important and sometimes-irreversible decisions—that I belatedly recognized the significance of testing's impact on teachers' day-to-day instruction. In short, for much of my own career, I was every bit as indifferent to what went on inside the testing tent as are many of today's teachers and administrators. I realize all too well what it is like to be assessment illiterate.

Quickly, about that label—"assessment illiterate." It's rare for productive educational conversations to ensue when someone who is less than expert about a topic is described in terms that could be perceived as derogatory or offensive. I have reservations about employing this term and discourage its use. It won't appear in the book beyond this introductory chapter.

Dispensation and a Promise

Because it is likely that you are an educator, I want to take a moment to disabuse you of what might be characterized as "entry guilt." If you are feeling remorse because you are not already assessment literate, I'd like to dispel that right now. It's not your fault, and you have plenty of company. Besides, by reading this book, you're putting yourself on the path to where you need to be.

Why Should Educators Become Assessment Literate?

The overriding purpose of this book is to help educators understand a handful of measurement concepts and procedures so that they can apply them properly to make sound instructional decisions and improve the quality of education that their students receive.

Moreover, becoming assessment literate will pay off personally for educators. The more they understand about the basic notions and processes that play a prominent role in educational decision making, the more likely it is that they will opt for the best choice among those decision options they face. These more defensible decisions will benefit the students under their care. They will make educators better educators—and this is something others will notice. Put candidly, if you are assessment literate, the odds increase that you will be regarded as a successful educator because—in fact—you will be a successful educator.

Making good decisions means avoiding mistakes, and the kinds of mistakes that assessment-illiterate teachers and administrators make fall into three categories: (1) using the wrong tests, (2) misusing results of the right tests, and (3) failing to employ instructionally useful te...