eBook - ePub

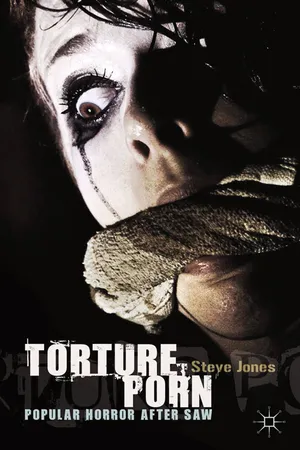

Torture Porn

Popular Horror after Saw

Steve Jones

This is a test

Buch teilen

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Torture Porn

Popular Horror after Saw

Steve Jones

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

The first monograph to critically engage with the controversial horror film subgenre known as 'torture porn', this book dissects press responses to popular horror and analyses key torture porn films, mapping out the broader conceptual and contextual concerns that shape the meanings of both 'torture' and 'porn'.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Torture Porn als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Torture Porn von Steve Jones im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas & Historia y crítica cinematográficas. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Part I

‘Torture Porn’ (Category)

1

‘The Past Catches Up to Everyone’:1 Lineage and Nostalgia

The aim of the following three chapters is to establish how ‘torture porn’ has been constructed as a category, outlining characteristics that have become associated with the subgenre. Part I will establish what ‘torture porn’ means, and the conditions under which those meanings are defined. The aim of examining ‘torture porn’ discourse is to clarify what the subgenre ‘is’ according to the critics who have propagated the term. As a starting point, this chapter addresses a paradox that arises within ‘torture porn’ discourse. ‘Torture porn’ appears to refer to a coherent category formed by films that exhibit mutual conventions and values. By providing a point of similarity, the label brushes over numerous discrepancies.

At the most basic level, torture porn films have been conceived as sharing a root commonality: torture porn is a sub-category of the horror genre. Yet, by distinguishing this subgenre as a unique grouping, the label contradictorily fosters the sense that torture porn is different to other horror subgenres. So, on one hand reviewers have overtly compared torture porn to earlier horror subgenres, such as slasher and splatter films, conceiving of torture porn as part of horror’s generic continuum. On the other hand, such comparisons have generally been unfavourable, painting torture porn as inferior (that is, entirely different) to past horror ‘classics’. The result is tension, which stems from the implication that both ‘torture porn’ and ‘horror’ are delimited, static categories, when they are more accurately hazy gestures towards imperfect, fluid, ever-evolving sets of conventions. Delineating a subgenre perfectly is impossible since both the subgenre and the overarching genre it belongs to are in constant states of flux. The relationship between torture porn and horror will be investigated in this chapter by probing the press’s conflicting treatments of ‘torture porn’.

Rather than accepting ‘torture porn’ as a label that simply encompasses a particular body of films then, the objective of this chapter is to examine the difficulties that arise from journalists’ uses of the label as if it signifies a fixed, delimited category. The inadequacy of ‘torture porn’ in that regard is evident. For example, although the label seems to encompass all torture porn films, in practice, the discourse fails to do so. At the time of writing, 45 films have been dubbed ‘torture porn’ by three or more separate articles in major English language news publications.2 Almost all of those films received theatrical releases in both the US and the UK.3 The many direct-to-DVD films that fit the ‘torture porn’ paradigm have thus far been neglected in ‘torture porn’ discourse. Theatrically released films have been scapegoated, meaning that the category has been mainly composed around a distributional context – the multiplex – rather than mutual conventions.

Torture porn’s content has been largely disregarded in press discourse. Consequently, the subgenre is characterised as having ‘sprung up’ from nowhere (Tookey, 2011), being constituted by films that are wholly distinct from earlier, ‘better’ horror movies. In actuality, the charges levelled at torture porn are uncannily similar to the scorn bestowed upon those ‘classic’ horror films torture porn has been unfavourably compared to. The desire to separate past from present reveals more about critics’ resistance to change than it does about torture porn. The segregation strategy – attacking torture porn while also defending ‘classic’ horror – fails to explicate continuities within the genre, or precisely what is allegedly wrong with torture porn. Deciphering the similarities between torture porn and earlier horror – in terms of filmic content and the discourses that surround horror film – illuminates both what torture porn putatively is and is not. Torture porn neither simply replicates nor overturns prior genre attributes. The subgenre has organically evolved from its generic precursors. By mapping out problems that arise from categorisation, this chapter establishes the groundwork for the remainder of Part I, which will be devoted to factors other than filmic content that influence how torture porn is understood.

‘Every Legend Has a Beginning’:4 shared facets and influences

Since ‘torture porn’ collects films under an umbrella term, it is necessary to grasp how the label itself speaks for and shapes responses to the films classified under that rubric. Understanding torture porn as ‘torture porn’ necessarily limits how each film is construed relative to that category. A cyclic logic is at play in such categorisation. Torture porn films are torture porn because they have been brought together under the banner ‘torture porn’. The label itself arose as a response to the films, and presumptions about their content. However, once in motion, ‘torture porn’ imbues any film categorised as such with meanings that do not belong to the individual film itself. Labelling any film ‘torture porn’ also entails washing over its idiosyncrasies, instead emphasising the presumed similarities it shares with other torture porn films.

Torture porn is conceived as a subgenre fixated on sex (‘porn’) and violence (‘torture’). This coalescence manifests in four contentions that will recur in various guises throughout this book. First, some objectors claim that torture porn is constituted by violence, nudity, and rape. Second, violence is read as pornographic. Critics allege that torture porn’s violence is depicted in such prolonged, gory detail that its aesthetic is comparable to hardcore pornography’s, since the latter is renowned for its close-up, genitally explicit ‘meat shots’. Third, the ‘porn’ in ‘torture porn’ is interpreted as a synonym for ‘worthless’. Since the films are allegedly preoccupied only with ‘endless displays of violence’ (Roby, 2008), they are dismissed as throwaway, immoral entertainment. Finally, it is proposed that the films are consumed as violent fetish pornography: that viewers are sexually aroused by torture porn’s horror imagery. Torture porn’s disparagement begins with these undertones, which are inherent to the label rather than the subgenre’s filmic content. The first two contentions portray torture porn as sexually focused. As Chapter 7 will demonstrate, this misrepresents the content of the films that have been dubbed ‘torture porn’. The latter two contentions are based on unsubstantiated assumptions about reception, which, as Dean Lockwood (2008: 40) notes, conform to the ‘limiting ... logic of media effects’. Such attempts to understand the subgenre favour paradigms that pre-exist torture porn over filmic content. As this chapter will evince, that strategy is ubiquitous in ‘torture porn’ criticism.

For the moment, it is worth contemplating what exactly torture porn films do have in common. The four contentions above do not necessarily harmonise, undermining the coherence implied by ‘torture porn’ and making it difficult to grasp why these films have been grouped together. However, critics have more consistently concurred about which films belong to ‘torture porn’ than they have about why these films should be denigrated. Stepping back from detractors’ insinuations and looking to the films themselves offers a clearer sense of torture porn’s root properties according to its opponents. Although diverse, the 45 films dubbed ‘torture porn’ by the press share two main qualities: (a) they chiefly belong to the horror genre and (b) the narratives are primarily based around protagonists being imprisoned in confined spaces and subjected to physical and/or psychological suffering. The subgenre’s leitmotif is the lead protagonist being caged, or bound and gagged.

Critics’ fleeting gestures towards filmic content can be utilised to refine those foundational commonalities. For example, although he is preoccupied with a contextual issue – audience reaction – Kim Newman’s (2009a) reference to torture porn’s ‘deliberately upsetting’ tone is worth considering. His grievance is surprising given that horror films intentionally foreground perilous situations, and so are customarily ‘deliberately upsetting’ in tone. It is unclear why torture porn should be singled out on those grounds. Newman’s complaint regarding the character of torture porn’s violence becomes more obvious when considering why some films have not been dubbed ‘torture porn’. Adam Green’s Frozen concentrates on three protagonists who are imperilled by their entrapment on a ski lift. The film has not been labelled ‘torture porn’ in major English language news articles despite (a) being marketed as a horror film, (b) prioritising entrapment themes, (c) setting the narrative in a restrictive diegetic space, and (d) focusing on protagonists’ suffering. Indeed, Green (in Williamson, 2010b) has posited that the film is anti-torture porn. There are two reasons why Frozen has not been dubbed ‘torture porn’: gore is kept to a minimum, and suffering is not inflicted by a torturer. In Frozen, the teens are accidentally rather than intentionally trapped.

Human cruelty and bloodshed are key triggers that influence opponents’ decisions about which films do or do not fit into the subgenre, and help to clarify what Newman means by torture porn’s ‘deliberately upsetting’ tone. The same implication is evident in Luke Thompson’s (2008) sweeping definition of torture porn as ‘realistic horror about bad people who torture and kill’. Graphic gore (‘realistic ... torture’) is paramount. By proposing that torture porn narratives are about ‘bad people’, Thompson equally alleges that torture porn narratives are invested in the calculated infliction of human cruelty.

Thompson’s assessment that torture porn is ‘realistic horror’ is another point of consensus among critics. Jeremy Morris (2010: 45), for instance, declares that torture porn is ‘never supernatural’. However, Somebody Help Me, Farmhouse, and Wicked Lake are among those contemporary horror films in which supernatural elements are mixed with abduction, imprisonment, and intentionally exacted torture. Such generic ‘slippage’ might mean that these texts fall out of the ‘torture porn’ category for many critics. Indeed, these hybrid texts have rarely been termed ‘torture porn’ in press reviews. It is equally telling that supernatural horror films such as Paranormal Activity and 1408 have been critically lauded specifically because they are not torture porn. John Anderson (2007a) and Kevin Williamson (2007b) both valorise 1408 because, in contrast to torture porn, the film lacks gore and is driven by ghostly forces rather than human intentions. Williamson’s and Anderson’s views confirm that torture porn is understood as a subgenre constituted by brutal spectacle. As is typical of such argumentation, both reporters assume that torture porn is gory, but do not evince that point with reference to torture porn’s content. They thereby connote that violent spectacle itself is not worth scrutinising. Since torture porn is reputedly constituted by such superficial violence, it too is denigrated.

Content is also eschewed in favour of context where torture porn is delineated via its roots. This is a popular method for determining the meanings of ‘torture porn’ in press discourse, yet the subgenre’s origins are again subject to disagreement. Assorted pundits peg torture porn’s progenitor as Hostel (Maher, 2010a) or Saw (Lidz, 2009; Floyd, 2007). Others cite the 2003 films Wrong Turn (Gordon, 2009), House of 1000 Corpses (Johnson, 2007), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Fletcher, 2009: 82), and Switchblade Romance (Newman, 2009a) among torture porn’s originators. One difficultly in pinning down torture porn’s starting-point is that the horror genre is replete with torture-themed films. Vincent Price vehicles such as Pit and the Pendulum (1961) and the uncannily Saw-like The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971) are only two examples that pre-date ‘torture porn’. Torture-based horror is clearly not the ‘radical departure’ some disparagers have claimed (Fletcher, 2009: 82; see also Di Fonzo, 2007). Ergo, torture themes and genre-affiliation are not enough to distinguish torture porn as a horror subgenre, since that combination pre-exists ‘torture porn’. The category-label was coined in response to a critical mass of torture-horror production at a particular moment.

A further defining factor is thrown into relief by the candidates for torture porn’s progenitor then: ‘torture porn’ is conceived as referring to torture-based horror films made after 2003. It is likely that pre-21st century horror movies will remain omitted from such analysis since they are anachronistic to the term itself. That torture porn is partially defined by era underscores the extent to which context is privileged over content in ‘torture porn’ discourse. Lockwood’s (2008: 41) question ‘how should we specifically distinguish torture porn from earlier horror cinema?’ is telling then, insofar as it underscores that the practice of labelling films ‘torture porn’ is precisely a distinguishing strategy: the aim is to separate torture porn from its generic past rather than examining what that lineage reveals about the subgenre. Fencing torture porn in this manner is a way of closing off rather than opening up meaning.

Although the majority consensus is that torture porn belongs to the 21st century, not all critics so sharply deny torture porn’s relationship to earlier horror. Some have rooted torture porn in late 19th century Grand Guignol (Anderson, 2007c; Johnson, 2007). In other cases, torture porn has been linked to previous subgenres such as the splatter film (Fletcher, 2009: 81; Benson-Allott, 2008: 23), to specific filmmakers including Herschell Gordon Lewis (N.a. 2010c; Johnson, 2007), Lucio Fulci (Kermode, 2010), and Dario Argento (Hornaday, 2008b), or to ‘classic’ horror touchstones such as Peeping Tom (Huntley, 2007; Kendall, 2008), and the original The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (Felperin, 2008; Safire, 2007). Numerous torture porn filmmakers explicitly concur with these correlations in their DVD commentaries,5 since doing so allows them to appropriate the cultural reputation those earlier horror films and filmmakers carry. Torture porn’s filmmakers and critics customarily share a respect for horror’s past, then. That similarity notwithstanding, ‘torture porn’ discourse is constituted by opposing attitudes to torture porn’s relationship with earlier horror. On one hand, decriers have dismissed torture porn by separating it from ‘classic’ horror. On the other, since torture porn is a horror subgenre and is compared to these past ‘classics’, its lineage cannot be evaded. These tensions become apparent when torture porn is compared to its predecessors.

‘I’ve seen a lot of slasher flicks’6

In seeking to establish what ‘torture porn’ is, critics recurrently use the slasher subgenre as a point of reference. Some have cited the slasher as a primary influence on torture porn filmmakers (Hulse, 2007: 17; Kendrick, 2009: 17; Safire, 2007). Others have referred to torture porn films as slashers (see Platell’s (2008) review of Donkey Punch, for instance). Furthermore, some torture porn films such as The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003) are remakes of slasher originals. These correlations are apt given that torture porn shares aspects of the slasher formula. Slasher narratives typically entail killers stalking teenagers in a specific locale such as Camp Crystal Lake in Friday the 13th, or the town of Haddonfield in Halloween. Torture porn’s imprisonment themes distil that formula by making it harder for protagonists to evade threat. Since they are often confined, escaping their tormentor is more difficult for torture porn’s captives than it is for the slasher’s teens. Torture porn’s adaptation of slasher films’ stalking conventions thus amplifies tension. When one character survives in torture porn – Wade in Invitation Only, or Yasmine in Frontier(s), for example – their freedom is even more hard won than it was for the slasher’s survivors. Torture porn increases the stakes by levelling the field. In torture porn, it is rare to find lead protagonists who are unambiguous...