Introduction

It is probably fair to say that “popular wisdom” in the twenty-first century identifies children’s work or labor as an aberration, an unfortunate and deplorable deviation from “normal” childhood. To the extent that work is acceptably ascribed to contemporary children , it is in the context of formal schooling where students do “seat” work, “group” work , “home” work, and so on. Not surprisingly, children as workers are virtually nonexistent in the academic study of child psychology. Yet there is growing cross-cultural and historical evidence that the majority of children made or still make vital contributions to the family economy. Work as a central component in children’s lives, development, and acquisition of culture goes unappreciated. This book aims to rectify that omission by reviewing and analyzing the very robust corpus of ethnographic, archaeological, and historic cases detailing children’s work. In the process, I aim to make the phenomenon of children’s work known to a much wider audience and to offer several theoretical advances in our understanding of the juvenile period in human life history.

In examining children’s work, it is immediately apparent that we are not dealing with a simple dichotomy or a phenomenon that can be captured by “coding” behavior and tallying “counts” of children’s work activity (Nag et al. 1978), as useful as they are. Children’s work is intimately bound up with local concepts of family , kinship, gender, economy, social rank, and socialization. Indeed, in most societies, work functions as schooling does in our society —as the means by which children develop competencies that mark and facilitate their passage to adulthood.1 The book highlights the centrality of learning and development in anthropological accounts of children’s work. Further, studies in cognitive development, infant cognition , in particular, reveal the evolved psychology that undergirds the skills that, eventually, coalesce into competent workmanship (Lancy 2017; Langdon 2013, p. 174). Other psychological processes implicated in children’s becoming workers include social learning, identity formation, prosocial behavior, autonomy, responsibility , and parenting behavior, among others. I’m suggesting here that studying children as workers across history and culture will enhance our understanding of the nature of child development which is often blinkered by the constraints of the monocultural, modern, middle-class population from which research samples are typically drawn (Henrich et al. 2010).

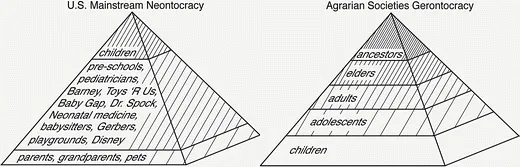

In my earliest attempt (Lancy

1996) to review and synthesize the study of childhood by anthropologists, I constructed a simple model that helped me make sense of the most important “finding.” I named this model “

neontocracy ” (us) versus “

gerontocracy ” (them) (Fig.

1.1).

2 This simple model crystalizes the contrast between “new” Western ideas about childhood and the ideas that have characterized humanity for millennia. Even prehistoric funerary remains bear out this juxtaposition of highly valued elders and lowly children. That is, we can tell the relative worth of the deceased from the location and richness of the internment, and these match the model.

In preindustrial society —a gerontocracy —children are typically engaged in an extremely wide range of activities that could be labeled “work.” Tasks like fetching water, caring for younger siblings , cleaning, gardening , and taking care of livestock are the necessary adjuncts of domestic life (Whiting and Whiting 1975, p. 84). Chores may be adopted voluntarily by children or assigned by a parent. From toddlers to teenagers , children are expected to help out according to their capacity and skill. Scholars have taken care to designate “children’s work” as tasks that are incorporated into family life and are “developmental ” where children are learning while helping. In contrast, children “labor” for wages or other form of remuneration, or to work off a family debt. This may involve removing a child from its family and exposing him or her to arduous and unhealthy conditions; and may not include opportunities for learning and advancement. In short, “labor” may be detrimental to children, at least in the long term (Bourdillion and Spittler 2012, p. 9).

We find a similar perspective using the lens of history. For example, in bas-relief funerary sculpture from the fourth to eighth century CE found in Rome, children as young as two are shown as workers—miners, grave diggers, charioteers, or weavers (Laes

2015).

There is a wealth of evidence to suggest that children have always worked and that children in poor and, particularly, rural communities have always been expected to contribute to the household at what might appear an extremely young age. It is equally important to acknowledge that parents have usually understood the need for protection of children and therefore drew lines between labor and exploitation . Children’s work was regulated by custom long before the Factory Acts and there were always boundaries which the overwhelming majority of parents and employers did not cross. (Brockliss and Montgomery 2010, p. 160)

Even among the elite, part of the child’s “moral socialization” included doing chores: “parents used little tasks to introduce their daughters to the working of a household and to adult responsibilities . Monica’s parents used to send her as a young girl to the cellar to draw wine from the cask ‘as was the custom’…Macrina is depicted as being engaged in household tasks and becoming a proficient woolworker even before she reached marriageable age. She even prepared meals for her mother with her own hands” (Augustine Conf. 9.8.17–8 as cited in Vuolanto 2013, p. 587).

Archaeology also yields evidence of children working: “in the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1700 BCE) children would have been important contributors to the household and the community. The deposition of tools made of bone, obsidian and stone, in child graves…could” reflect the tasks assigned to the interred children (Gallou 2010, p. 162). Later, decorated vessels from classical Greece clearly show children at work (Oakley 2013).

Helpers, Workers, Artisans, and Laborers

Used throughout this book, the complementary

terms “Helpers,” “Workers,” “

Artisans,” and Laborers convey the profoundly developmental and social nature of work during

childhood. “Developmental ” and “social” take on an extended meaning in my analysis. That is, work is inherently developmental because children

learn skills

as they work and is inherently social because most skill learning

occurs in the process of working

with and for others. These four stages convey a progression from:

- 1.

Helpers who are younger, less competent, less responsible, and more play-oriented children can, nevertheless, help out by, for example, running errands. They may not be acquiring skills per se but are certainly socialized into the role they’re expected to play in the family.

- 2.

“Workers” are older, more skilled, and more responsible participants whose list of daily chores—carried out without the need for supervision—may be long and time consuming. Their socialization into their roles as workers is complete but further development is driven by the growth in skill, strength, and dexterity. Workers become more productive and useful as they get older.

- 3.

Artisans appear when societies reach a certain level of complexity which justifies the production and often the sale of more durable goods. Children interact with crafts from early childhood by, as examples, play-weaving using a toy loom and play-pottery using donated clay and shaping tools. By middle childhood , the future artisan will be fully engaged in learning the craft from observing a parent or other competent and supportive expert . Where the goods produced are of high symbolic and/or trade value, opportunities to learn may be limited to a formal apprenticeship which may have many attributes in common with becoming a laborer.

- 4.

Child laborers are those children and adolescents who, through necessity or opportunity, are engaged in a narrow range of physically demanding jobs which yield a material return that benefits the individual and his/her immediate family. A very significant change is the loss of the youth’s autonomy to manage his/her own work activity and further skill development.

This fourfold division is an organizing device to help bring order to the material under review but, in the field, it can be difficult to distinguish between, say, helping and working. While this particular parsing of childhood is my invention, these distinctions and corresponding labels can also be found in the literature (Grove and Lancy 2015). For the Gamo in southern Ethiopia, the social status of the child is closely connected with the tasks that she or he performs. Up to the age of about five children aren’t assigned chores. They are called Gesho Noyta. Children from five to ten are called Nāo; they assist their parents. Finally, Wet’te Nāo are girls and boys who’ve assumed full responsibility in various routine domestic and agricultural activities (Melaku 2000, p. 32).

A brief ill...