In 1887, an unsigned article in The Globe and Traveller depicted the typical experience at an isolation hospital operated by the Metropolitan Asylums Board (MAB) : “It requires a certain amount of courage when, after a few days of headache and depression, your doctor announces that you have scarlet fever, to take his advice and consent to be removed to the fever hospital.” You have your family to think about though, and so the ambulance is sent for. Dressed in hospital garments, you are carried downstairs in a stretcher to a waiting ambulance, a nurse jumps in, and immediately you are “off through the streets.” You recall being miserably sick for the first few days in a large scarlet fever ward, not a single private room being available. “The fever gradually abates, however; your nerves become less irritable, and you begin to watch all that goes on in the ward with interest.” A medical student from St. Bart’s in the next bed criticizes the nursing at every step. The other patients are a very mixed lot, but you are able to strike up friendships over common complaints; yours is the want of readable books (the hospital oddly being chock-full of “semi-religious rubbish and dirty French novels”). Visitors are not allowed unless you turn dangerously ill, and therefore “the feeling that you are either in a gaol or a lunatic asylum gradually grows upon you.” Toward the end of the period of confinement, the subject of “peeling” occupies your mind. The lucky scarlet fever convalescent will expel the flaky rash in about six weeks and, knowing you will not be allowed to leave until this process is complete, you seek to hasten the process by scrubbing yourself with pumice stones and rough towels until raw all over. Finally, passing out through the hospital’s iron gates at the end of this ordeal, you may take heart that your healthy family awaits you—“health which you probably secured to them by your timely flight from their presence.” 1

The journalist does not attempt to completely own the experience, and the second-person voice has the effect of inviting readers to place themselves in the hospital. Although it certainly may have been to some extent worrisome, the proposition of submitting to a period of isolation could not have been entirely strange in 1887, and the author makes it seem like an ordeal for which nearly everyone might do well to prepare. In fact, the author of the piece was Honnor Morton, a young hospital-trained nurse from a privileged background just starting to make a name for herself as a writer and activist in a number of causes. 2 Morton’s short stories—mostly sketches of hospital life populated with nurses, doctors and patients—are strikingly backgrounded with figures of disease and suffering. They drive home the devastating extent to which infections like typhoid and scarlet fever were still relatively commonplace and amounted to a significant cause of death in London. Her piece for The Globe and Traveller is likely based on her own bout of scarlet fever in about 1887. “It was so ugly and lonely at that fever hospital,” she recalls in a semi-autobiographical journal published years later. For Morton, the disappointment was an initiation to stark social realities that would mark her career in district nursing and an all-female settlement house in the East End slum of Hoxton. Another of her short stories involves the intense anxiety caused by a lack of vacancies for fever victims. 3 Typical of the intersection of socialism and feminism in her day, Morton also could be highly critical of the authority wielded by doctors. She wrote, for instance, about the dehumanization of women in the course of ordinary medical examinations, but made this an argument in favor of the municipalization of all hospitals. 4 A recurring theme in Morton’s writing is isolation: personal, emotional, and institutional . While these appeared often as negative and limiting, it is worth noting that forms of separation also become in her stories (as in your sojourn at the fever hospital) the positive means of ordering life, safeguarding others, and realizing broader purposes.

Morton’s little story touches upon the significant transformation of the hospital landscape in Victorian London—a transformation that structured in very powerful ways the individual experience and public regulation of infectious disease. She perhaps simply perceived a little more intuitively than others at the time just how importantly

isolation integrated one’s individual performance as a central component of that governance. Sanitary detention and confinement was in the middle of a contentious process of becoming another mundane part of urban residence. Indeed, being shunted off to the infectious disease hospital for several weeks was soon no longer a necessarily extraordinary event. An epidemic did not need to be raging—it was a measure intended to manage the normal prevalence of urban

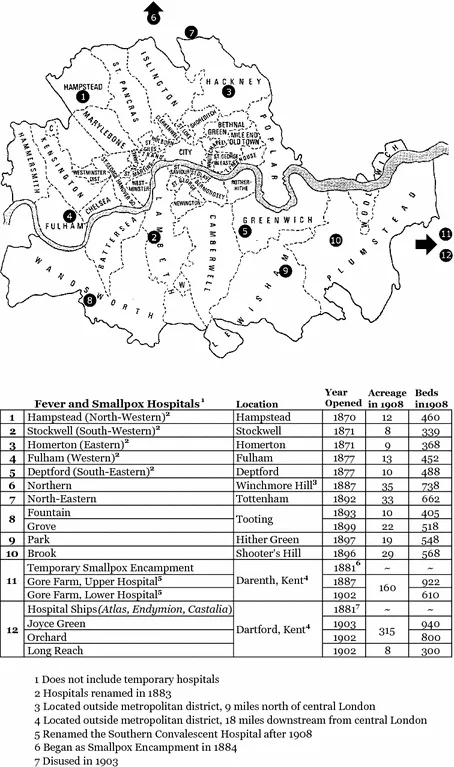

contagion . When Morton’s story appeared in 1887, the MAB had been in existence for two decades; it now operated nine

fever and smallpox hospitals with a combined capacity of nearly 5000 patients. The MAB hospitals had originated as a collection of rickety sheds for sick paupers but rapidly grew into an adept network of specialist hospitals and ambulances for all Londoners. By 1903 it possessed fifteen hospitals and over 9000 beds (Fig.

1.1). Between 1870 and 1900 the MAB took in a total of 307,840 patients suffering from smallpox, scarlet fever, diphtheria, typhus, and typhoid. At the end of this period the

fever and smallpox hospitals were receiving at least 25,000 Londoners per year. “No student of disease, or even of sociology, can fail to watch the work of the Metropolitan Asylums Board,” remarked

The Lancet in 1897.

5 Hospital isolation had emerged as one of the most common ways that ordinary persons came into contact with state medicine.

We can legitimately speak of a “great confinement” of infectious patients in London in the last decades of the nineteenth century. Yet this did not generally correspond to a great rise of epidemics. In fact, just the opposite: many of the most feared

contagions like typhus and smallpox were rapidly fading into metropolitan obscurity. Others like scarlet fever and typhoid were as prevalent as ever, but actually declining in average deadliness. One writer surmised that fifty years earlier an edict for the removal of

fever and smallpox patients from their homes would have met with “the most determined resistance.” Nothing of the sort was needed now, he happily concluded, because

… even among the most ignorant and suspicious of the London poor, these hospitals are mentioned with gratitude. The little patients are entrusted to them by the parents with unbounded confidence, and stories of kindness and real sympathy exhibited are related no less cordially when the disease has proved fatal than when the patient has been restored in full health to his friends. 6

Even allowing for the usual amount of journalistic exaggeration, how could this have come to be? Londoners were asked to enter isolation, and eventually did so without very much fuss. They made themselves available to health authorities, allowed their bodies to be counted among the dangerously sick, and became liable in entirely new ways to bureaucratic structures of health management. As this book is about governance, health, and institutions, it will ask what policies, discourses, and materialities contributed to making the isolation hospital a constant possibility. As it is also about liberalism, the following chapters will enquire as to how the objectives of public health were determined by the sort of relationships that could be forged between institutions of sanitary governance and the persons who were to be sanitarily governed.

London’s surprisingly extensive archipelago of hospital isolation was in some ways clearly an epitome of the bureaucratic state and its regulation of life. But this book is also interested in examining how that form of infectious disease control depended upon and in turn supported the conception of a self-governing citizenry. The Times was just one of a number of outlets that believed the successful mitigation of disease by hospitalization could “only be carried into effect by the intelligent cooperation of the public.” 7 According to another writer, the isolation hospital provided an opportunity for practicing equal treatment in the face of a force of nature. The “dreams of democracy,” he concluded, seemed to be “very nearly translated into fact by the strange bedfellows with which fever may nowadays make men acquainted.” He reported that on a recent day one MAB ward contained a prosperous traveler who had been staying at the Hôtel Cecil and another person from a slum in Whitechapel. 8 Clearly, what at first glance might seem an enormous carceral arrangement for the detection, detention, and discipline of unruly bodies and social outcasts might be, upon any closer inspection, much more complicated and intriguing. This novel apparatus of health security transformed essentially all bodies into potential infectious threats, subject more or less to the same techniques of separation. A key goal of health authorities was to get the public to accept and even expect treatment for infectious diseases in such institutions. Isolation was a form of detention and confinement—but it was not always a lonely spot of exile or a place for stockpiling and forgetting society’s outcasts.

This is not to say that the rise of hospital isolation was not controversial and disruptive in a number of ways. To be sure, it was viewed as potentially intrusive to the liberty and status of the individual and the sanctity of the private home. The expanding network of hospitals undoubtedly contained more than a hint of incarceration, and never completely dispelled the strong punitive aroma of restraint, discipline, and control. And yet, in the end the isolation hospital was not incontestable. In fact, it was always actually highly contested, and London provided the ...