eBook - ePub

Open Borders, Open Society? Immigration and Social Integration in Japan

Toake Endoh, Toake Endoh

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 210 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Open Borders, Open Society? Immigration and Social Integration in Japan

Toake Endoh, Toake Endoh

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Is Japan prepared for an ethnically diverse society? The volume examines the past and future trajectory of Japan's immigration and integration policies and related institutions, taking a cross-disciplinary approach in social sciences. The authors highlight critical issues and challenges that the nation is facing as a result of the government's inarticulate migrant-acceptance policy, e.g. in the fields of deportation, refugee policy, multicultural education and disaster protection. How can the situation be improved? The book investigates the changes and initiatives needed to build a resilient policy regime for a liberal, pluralistic, and inclusive Japan.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Open Borders, Open Society? Immigration and Social Integration in Japan als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Open Borders, Open Society? Immigration and Social Integration in Japan von Toake Endoh, Toake Endoh im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Politique et relations internationales & Politique de l'immigration. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

National Immigration Policies

[41] Chapter 1

Problems from Leviathan’s Cells

Toake Endoh

Introduction

At long last, Japan, a longstanding immigration restrictionist, opened its front gate to less-skilled foreign workers. Legislative approval of revisions to national immigration control in April 2019 paved the way for funneling less-skilled labor from overseas to specific industrial areas that could not secure a workforce domestically (fourteen labor-intensive sectors as of this writing).1 This policy change may straighten out the obscure earlier “foreign worker acceptance” policy—Japan’s phraseology favored over “immigration”—and accelerate imports of acutely needed basic workers across the nation.

From a structuralist perspective, the trajectory of immigration liberalization seems inevitable and irreversible, given persistent and worsening depopulation and labor shortages (Akashi 2009; Blind 2017; Green 2017; Menju 2017). Theories of political clientelism (for instance, Freeman 1995) or the rational choice approach of new institutionalism (for instance, Collier 2013) may explicate that, under macro-economic and demographic pressure, the government of Japan (hereafter “GOJ”), nudged by organized economic interests, made a rational choice to fill labor slots with a temporary, flexible, and cheap workforce from overseas. Shifting our attention to the nation-state, however, we see other institutional developments underlying the easing policy: the Japanese state—beyond its Marxian functional role as the “executive committee” of business—has been reinforcing the restrictive immigration regime in parallel with liberalization. More specifically, Japan’s immigration control and enforcement authorities are increasing their influence via regulatory institutions and actions, pivoting to internal control beyond borders in order to limit unwanted migration (Endoh 2019, 2021; Takaya 2018).

In international migration studies—where history, economics, geography, sociology, or anthropology prevail—calls for research focusing on the sovereign [42] state are coming from political scientists, acknowledging the significant role and impacts of the sovereign in shaping cross-border human flows (Bigo 2002; Hollifield 1992, 2004; Massey, Durand, and Pren 2016; Zolberg 2001, 2006; Zolberg, Suhrke, and Aguayo 1989). Such proposals are all the more relevant in the twenty-first century, rife with global crises, economic, political, or humanitarian—one of the latest and gravest being the COVID-19 pandemic— that affect international migration. States, confronting mass immigrations and migrants’ settlements, step up to protect borders and territorial integrity or safeguard their society and people—including migrants (under liberalism) or excluding them (by nativists) (Hollifield 2004; Huntington 1996, 43-45; Walters 2018; Weiner 1993; Zolberg 2001). Under such circumstances, immigration control and enforcement beyond ports of entry have weighed in (Broeders and Engbersen 2007; Lahav and Guiraudon 2000; Zolberg 2001). Making and enforcing laws, rules, and measures against unwanted immigration are generally understood as sovereign rights of the Westphalian state, which is innately “garrison [i.e., exclusionary]” (Hollifield 2004, 888; Nyers 2003). In liberal democracies, exclusionary governance—to capture and extradite unwanted aliens, be they unauthorized migrant workers, “sham” asylum-seekers, trafficked persons, or subversives—has been deemed “unattractive” normatively and politically and often just a “symbolic” gesture (Hollifield 2004, 897). But in a crisis-festered world like today’s, upended by a pandemic, a poignant public temperament looms that favors exclusionary policies as necessary and legitimate (De Haas, Natter, and Vezzoli 2018). A growing austerity and exclusion behind immigration-easing also characterize Japan’s policy disposition, as illustrated below.

Administration of immigration enforcement is a major component of exclusionary governance. Immigration professionals are more than mechanical executors of established law and procedures. Employing specific strategies, methods, or technologies, enforcers on various administrative levels exercise their organizational (or individual) powers over migrants and determine the latter’s everyday life and future (Broeders and Engbersen 2007; Huysmans 2006; Huysmans and Squire 2009). With the mindset to frame migration or unauthorized immigrants in a security or criminal context, gatekeepers “radicalize exclusions and legitimate violence” (Huysmans and Squire 2009, 12). Whereas immigration law draws a non-territorial boundary between insiders and outsiders and “produces the illegality” of unauthorized migrants (De Genova 2002), immigration administration, through its everyday operations, substantiates the boundary. Further, immigration agencies, equipped with discretionary power and institutional autonomy within the state, may claim that [43] the license to exclude is vital for swift, flexible, and effective immigration management, often violating migrants’ rights.

Japan’s gatekeeper, the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) and its immigration control outpost, the Immigration Services Agency (ISA), provide an example of such a rigorous and autonomous immigration bureaucracy augmenting its restrictive arms as a balancer of immigration easing. These control and enforcement authorities and their impacts upon migrants are so significant that they merit more scholarly attention. (Many relevant studies are only available in Japanese; for instance, Akashi 2010; Furuya2011; Takahashi2016; Takaya 2018; for works in English, see Chung 2010; Endoh 2019, 2021.) How has Japan’s immigration control and enforcement regime been developed? What legal or institutional sources bolster its agencies’ extra-judicial power and status and relative autonomy within the state? And at what costs, organizational, normative, or human? Below, I try to answer these questions.

Parallel Development of Immigration Restriction and Easing Institutions

As demonstrated in the introduction to this volume, Japan’s immigration policy has been on a trajectory toward liberalization since the 1990s. The Japanese government led by the conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP: 1955-1993; 1996-2009; 2012-present) or liberal-leaning coalitions (1993-1996; 2009-2012)—has imported foreign workers, mostly from Asia and South America, in order to meet the nation’s acute and chronic labor shortage. Meanwhile, the enduring conservative mantra “Japan does not accept [basic] labor immigration” stands firm.2 Absent explicit national consensus—and the GOJ’s avoidance of building one—on longer-term or permanent settlements of foreign nationals in the country, the way in which legal changes and new policy arrangements necessary for acquiring high- and less-skilled foreign workers have been made is incremental, piecemeal, and awkward (Akashi 2014). The latest revision of the immigration law in December 2019 broached a major policy shift from the past awkwardness of opening the “front gate” to less-skilled workers—although their longer- or permanent stays are limited by design (Milly 2020). As a result of immigration easing, the tally of foreign-born workers [44] made a sixteen-fold increase in twenty years, to more than 1.659 million as of October 31, 2019 (MHLW 2019).3 Foreign-born residents have also increased to 2.93 million in 2019 (MOJ 2020).

Behind the rapidly changing ethnic landscape, the MOJ and the ISA (formerly the Immigration Bureau of Japan, spun off from the MOJ in 2019) have steadfastly reinforced their restrictive arms. If foreign worker acceptance is unavoidable, it must be well-regulated, they assert. From the early 1990s, the MOJ started to institute a series of stringent rules on the entry, residence, and deportation of foreign nationals.

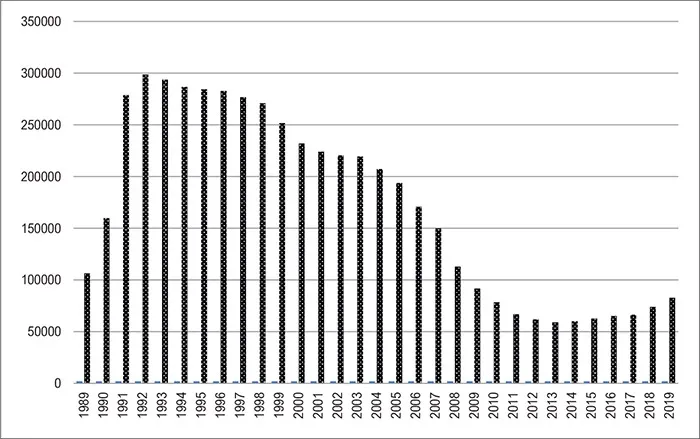

The Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act (formally, Government Ordinance No. 319, in effect October 4, 1951; hereafter “ICA”) is the only law governing Japan’s immigration administration. Under the law, the ISA administers the visa status and activities of foreign nationals in three areas: (1) immigration control (or landing examination), (2) alien resident management beyond ports of entry, and (3) emigration control (or deportation). The immigration authority seeks to ensure “smooth acceptance of foreign nationals beneficial to our [i.e., Japanese] society,” based on visa status or position, and “exclude (haijo) foreign nationals harmful to us” or sources of “disturbance of safe and secure society” (MOJ 2010, 29). The causes of disturbance identified by the MOJ vary depending on the historical context: during the Cold War period they were communist, anti-state, or anti-war activities; since the 1990s, cross-border organized crime; international terrorism after 9/11, or hooliganism at the 2002 Soccer World Cup. From the early 1990s, the authorities have been focusing on unauthorized stayers, especially Asian workers without a valid visa. In 1992 alone, as many as 298,646 unauthorized stayers were apprehended (Chart 1).

[45] Chart 1: Number of unauthorized stayers

Source: MOJ, Shutsunyūkoku kanri tōkei tōkeihyō [Chart of statistics on immigration control], 1989–2019.

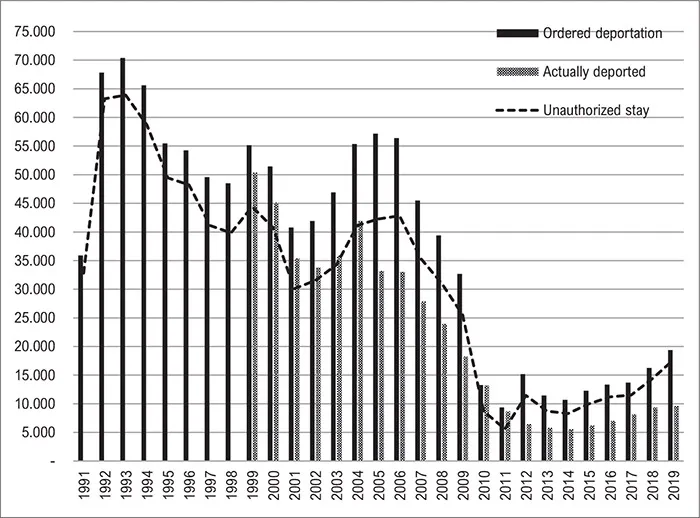

[46] Chart 2: The number of deportation cases, actually deported, and unauthorized stayers (1991-2019)

Source: MOJ, Shutsu nyūkoku zairyū kanri gyōsei kankei tōkei [Statistics on immigration and residence control administration], 1990–2002; MOJ, Shutsunyūkoku zairyū kanri, dai ichibu, shutsunyūkoku o meguru kinnen no jōkyō [Immigration and residence control, part 1: Recent situations of immigration], 2003–2019.

Chart 2 presents a history of the number of deportation cases, ordered deportations (indicated by dark bars) and those actually deported (lighter bars), as well as the unauthorized stayers subject to deportation (expressed as a solid line). It is clear that most deportation cases concerned overstay (or “unauthorized stay” in MOJ terminology), 80.4 percent on average during the period of 1991 to 2019.4 Overstays are arguably less threatening to national security and public safety than criminal offenses (e.g., thefts, fraud, and felony), which made up 2.3 percent of the total deportation cases in 2019. Still, nonviolent [47] misdemeanors have been singled out since “most overstayers work in Japan illegally, which could upend the very foundations of the status-of-residence system that is central to [Japan’s] immigration control administration” (MOJ 2000). What Schuck calls a “victimless offense”5 is not overlooked by the immigration bureaucracy for whom law and order is paramount and is thus shortlisted for removal.

Chart 3 tabulates major rules and institutions introduced to liberalize (L) or restrict (R) immigration since 1989. Restriction is broken down into three sub-categories: landing, residence, and deportation. The chart illustrates that the trajectory of the institutionalization of immigration restriction has run parallel to that of easing. In short, the wider the immigration gate opened, the tougher the grip of control became. This dualistic approach bolsters a “strict rotation policy” to import temporary and flexible workers while discouraging permanent residence. Highlighted “parallel” developments include: criminalization of the incitement of illegal employment [against employers] in 1990 and exposure of IC A violators from 1991 while a new visa status for talent and nikkeijin (foreign nationals of Japanese ancestry) was prepared in 1990; criminalization of overstays in 2000 and the campaign to “halve irregular stayers” starting in 2003 in parallel with the expansion of the Technical Intern Training Program (TITP) to special economic zones in 2002; and the introduction of the mandatory Resident Card system, contemporaneous with the points-based system for talent migrants, both starting in 2012. The immigration authorities’...