![]()

From the mid-nineteenth century onwards in Germany, a new kind of ethic entered into the architectural imagination, centred on the household. This household was conceived in a twofold social context, referring both to the traditional family household and to a household that was only just coming into being: the nation. The family and the nation became fundamental points of reference in a large number of academic fields concerned with epistemological questions over the nature of modern society. In broad terms, these fields included political science, economics, ethnography, and, indeed, architecture. Both family and nation began to be viewed in these fields as engaging in a dynamic social interplay, albeit one moving towards equilibrium rather than enacting a dialectical transformation. The growing impulse to manage this dynamic – to enable a kind of ‘visible hand’ of social government – was based on a growing belief among a variety of experts that knowledge procured from the family household could be used to reform society and regulate the economic growth of the nation at large. This reform project came to underpin a new ethic in architecture, which called for the discipline to reconsider the terms of its agency within a framework of society that privileged the operations of the family home.

The intellectual scaffolding for this project came from a curious source: the conservative folklorist and proto-sociologist Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl (1823–97), whose mandate of ‘building from the inside out’ achieved immense popularity among modern architectural critics and theorists. Folklore research exploded across Europe in the nineteenth century as nations sought to strengthen their political identity through studying their native traditions, including oral languages, epic poems, songs, and building practices.1 The need to acquire social knowledge of the broader German population was growing in importance leading up to German unification. Previously to that, the German Empire consisted of scattered territories that possessed their own systems of administration and statistical information. While romantic folklorists like the Grimms sought to recover German values and customs in order to bolster national understanding, the more rigorous folklore emerging in Riehl’s work served a dual purpose of pragmatic social inquiry and administrative intervention.2

In the context of Riehl’s folklore studies, ‘building from the inside out’ referred to the traditional Germanic spirit that appeared to pervade pre-modern ways of building. It connoted certain types of buildings, such as ramshackle cottages and quaint chapels hidden in the woods, from which the spirit of the German people seemed to emanate through their very materiality. Instigating a polemic on the importance of the traditional German family as well as fuelling anti-Semitic, anti-Romani, and anti-Ottoman sentiment, Riehl’s conservative folklore played a crucial part in building German national identity. While Riehl’s social theory was ideologically conservative in its endorsement of both the pre-modern estate system and the extended family as models of social self-sufficiency in the modern era, his methods and assumptions were novel. He perceptively recognised that cultural knowledge of the German population could be used as a vital source of modern political power. In this sense, Riehl’s work represents a critical moment in which the rhetoric of architecture was transferred from an epistemological frame considered too static, abstract, and philosophical to a frame considered dynamic, concrete, and scientific. It was the latter frame that modern architecture came to occupy in its turn to housing as a privileged field of architectural intervention.

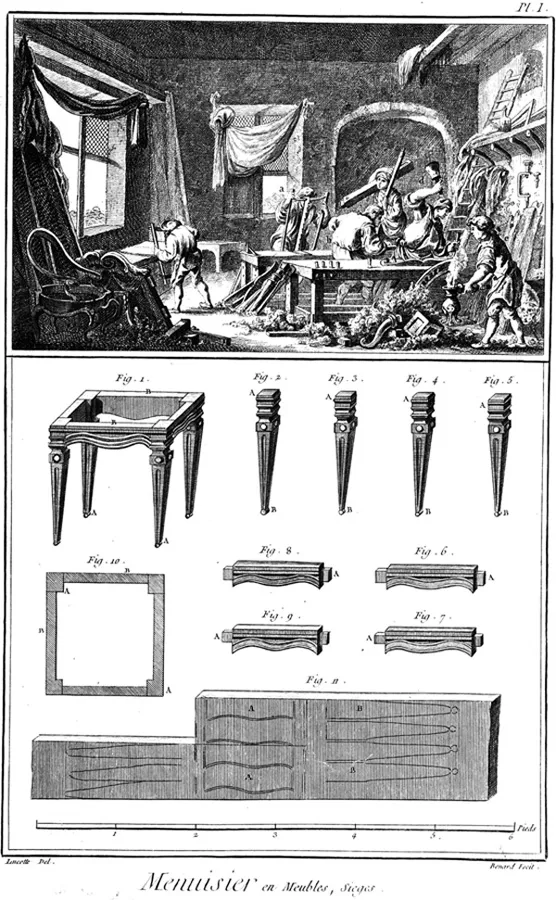

Riehl’s style of folklore research was ineluctably shaped by the aftermath of the 1848 revolutions, when the tenets of Enlightenment social politics were being violently put to the test. The waves of revolutionary upheaval that swept across the states of the German Confederation in 1848 resulted in major political and social fragmentation that prevailed until the unification of Germany in 1871. Within the burgeoning social sciences, numerous efforts were made to interrogate and challenge the philosophical assumptions that underpinned the socialist movements believed to be the main culprits of the unrest. Concerns over the threat of organised labour movements emerged across Europe as soon as the medieval guild system collapsed. French philosophes Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d’Alembert were the first to reflect on the social effects of industrial labour conditions, dedicating a significant portion of their monumental Encyclopédie (1751–72) to representing the state of the ‘mechanical arts’ in France – in part an effort to reveal trade secrets and thus undermine the strength of the guild system. Yet Diderot’s documentation conveyed a degree of sympathy for the state of workers’ wellbeing under dispersed guild-based conditions – conditions which were disappearing through the increasing centralisation of industrial production. In his entry on the state of industry, Diderot warned of the dangers of the large factory for breeding workers’ exploitation and discontent, encouraging instead the dispersion of manufacturing via smaller-scale workshops (Figure 1.1).

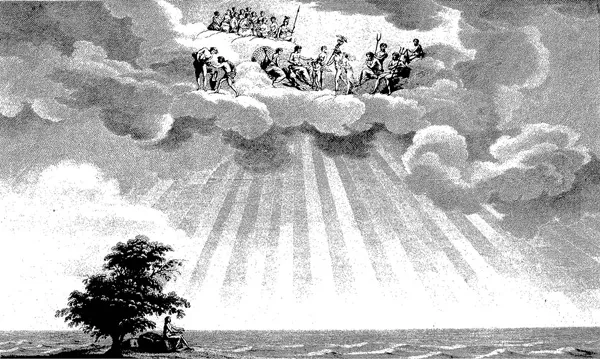

French architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux’s designs for workers’ houses, published in his 1804 treatise Architecture, represent some of the first proposed architectural solutions to the growing problem of social alienation under modern industrial conditions. These designs were dually intellectual and didactic. His model for a worker’s house at a saltworks company town in Chaux was a utilitarian design overlayed with a Palladian grammar. His designs for rural workers’ houses displayed a similar paternalistic intent, with a woodcutter’s house and workshop affording dignity to the woodcutter’s hitherto unruly trade in the forest by articulating it in the classicising grammar of a primitive wooden order. These workers’ houses represented Ledoux’s attempt to reconcile Diderot’s two models of unified and dispersed manufacture into a single architectural vision of the French physiocratic landscape. This vision was both enlightened and consoling, seeking ultimately to reform disorderly workers’ associations by constructing a bucolic, quasi-feudal image of ‘productive man in a physiocratic arcadia’ in accordance with the language of high architecture.3 The social gulf opened by industrialised work could be thus reconciled through Enlightenment ideals. Accordingly, Ledoux assigned a prominent place for the figure of the architect in his vision, with another plate in his treatise depicting a poor man standing under a solitary tree, hands reaching out to be struck by the rays of sunlight cast by an architect standing in the clouds among the muses of art and science (Figure 1.2).4

Early-nineteenth-century utopian socialist sects born in France continued to ignite conservative fears in Germany over the growth of secret societies, unionisation, and revolution. While based on an Enlightenment faith in a renewed social world born from the power of the intellect, these sects possessed a feverish religiosity, worshipping the artisan as a cult figure within their visions of cooperation.5 In Germany, the conservative reaction against the spread of mystical socialism reached its peak in the work of Riehl in the wake of the turbulent revolutionary years. His populist writings on German society were instrumental in bringing to an end the influence of utopian socialist doctrine, which had quickly spread in Germany by means of popular pamphlets combining ‘apocalyptic reference to the end of the world’ with ‘vernacular prophesies about the nation’s political future, Delphic monastic oracles, and predictions of clairvoyants’.6

Riehl saw the benefits and dangers of the French encyclopaedists’ approach from the previous century. In taking stock of the past and present goals of social reform, he praised their empirical work, but criticised their impulse to apply quasi-universal values (Rousseauesque abstract notions of a ‘social contract’) to the social conditions they documented in the French countryside – which were largely responsible for the spread of the kinds of radical doctrine Riehl feared. If the question of reform for Ledoux was still largely framed in terms of what could be done for the worker (the gift of intellectual refinement brought by the architect-philosophe), the question of reform for Riehl concerned what could be done to the worker.

Towards this task, Riehl took inspiration from the empiricism of conservative German jurist and historian Justus Möser, whose epic account (published 1768–80) of his own native town of Osnabrück (a Holy Roman principality in northern Germany) is widely held to be the first social history. Like Diderot and Ledoux, Möser nostalgically seized upon idealised images of pre-modern craft production, using them as guiding threads in his historiography. One such image, to which Riehl was particularly drawn, described the prototype of a Saxon farmhouse, which Möser believed characterised Osnabrück’s peasant life from the era in which the Roman scholar Tacitus wrote Germania (98 ce) to his own time.