![]()

Part I

Sexual Embod(y)ment

Framing the Body

![]()

Chapter 1

Entering through the Body’s Frame

Precious and the Subjective Delineations of the Movie Poster

Kimberly Juanita Brown

There is power in looking.

—bell hooks

Body Impossible

Before Precious was nominated for four and won two Academy Awards, there was the all-important Sundance Grand Jury Prize, which the movie won in a triumphant display of limited cinematic and restricted envisioning of black women’s lives and sexual experiences.1 Voted into the “oblivion of hypervisibility,” viewers and voters were determined to make their mark on that ubiquitously overburdened text: the black female body.2 They have done this before and do this still, but with Precious the stakes were higher. The transformation of the protagonist’s fictional body into a visual text provided space for a feigned engagement—what I like to call the “head tilt of sympathy”—in which a performance of engagement takes place repeatedly but only within the space of ineffable and unimaginable sexual trauma. This is where black women are offered up in pieces: as broken, bruised, fragmented pseudo-subjects seeking redemption through white empathetic renderings of collective suffering.3 Sexuality is rendered here as a violated corpus: a grand jury prize for a body impossible. This essay looks at the origin point of this interaction—the marketing space of the movie poster—and explores the currency of print imagery in the reiteration and reinforcement of the viewer’s hegemonic incline through the black female subject’s racialized and gendered decline.

The Derivative Riff of Poster Imagery

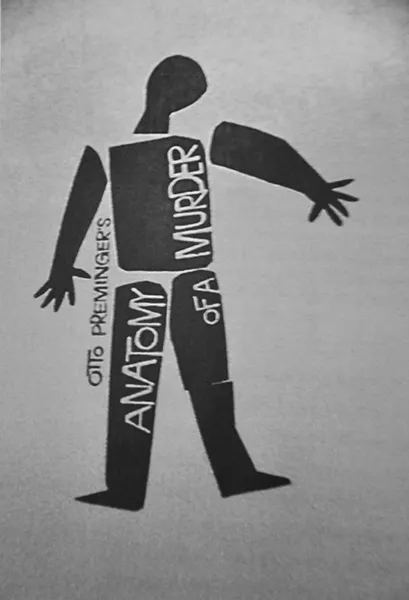

Consciously engaging the artistic sensibilities of early motion picture poster production, the initial (and probably most recognizable) graphic image for the film is an homage (if we can call it that) to Saul Bass, specifically the image he produced for Otto Preminger’s 1959 film Anatomy of a Murder. Striking and provocative, the Bass image features a body displayed in vertical silhouette against a burnt-orange background. The body is severed at the waist, arms, and neck; it is decapitated and in a state of dissection (see figure 1.1). The title of the film is written on the body’s torso and thighs, and the “anatomy” taking place begins with the poster’s marketing of the courtroom drama starring James Stewart and Lee Remick.

Saul Bass’s ability to trouble the line between artistic production and consumer marketing made him a sought-after and prolific illustrator (he created the posters for Vertigo and The Godfather).4 Art Sims’s image for Spike Lee’s film Clockers (1995) is a relational duplication of the Bass graphic style.5 One of the movie posters for Precious followed the poster for Anatomy of a Murder stylistically (more so than Clockers), but it diverges from the original in very important ways. These distinctions offer us a more layered context through which to read the film, its presumed audience, and the often-unacknowledged interplay of black female subjectivity and representational imagery. They are a way into the concept of the racial imaginary and a useful place to begin.

Movie posters originated as advertisements for traveling circuses, according to Gary D. Rhodes. “It is very clear,” he writes, “that the early film industry believed that the circus poster had led to the creation of the moving picture poster.”6 As a given in our image-thick visual environment, movie posters have lost some of their wonder amidst the static expectation of their arrival. We expect to see them. Nevertheless, whether viewed on the Internet or on a moving billboard in Times Square, they still have an immediate and visceral impact. The initial teaser poster for Precious aimed for that impact and achieved it by participating in the long and egregious visual history of objectifying black women’s bodies. “If media are middles,” W. J. T. Mitchell writes, “they are ever-elastic middles that expand to include what look at first like their outer boundaries. The medium does not lie between sender and receiver; it includes and constitutes them.”7 Film posters are often the first point of visual contact between the film and the viewer. They can layer expectations with their static imagery, allowing the viewer to parse out the particularities of their investment one unbridled visual infraction at a time. This is especially so with movie posters, and films like Precious, that showcase black women’s bodies and in turn provide occasions for viewers to both witness and visually enact violence against black women’s bodies through spectatorship.

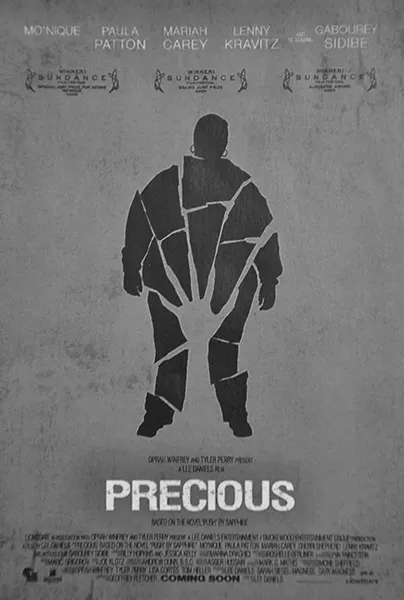

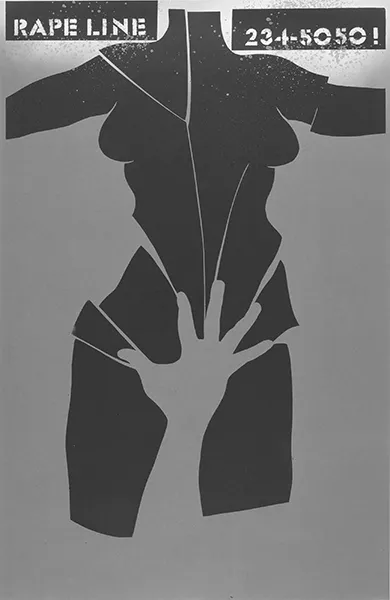

The first of four promotional images for the film Precious, generated by the Los Angeles graphic design company IgnitionPrint, featured a large-bodied female in silhouette. Her whole body is cracked and fragmented (figure 1.2). The origin of the fragmentation is a large left handprint strategically placed on the figure’s vagina, while diagonal lines emanate from the hand. There are two main points of divergence from the Bass image, and both of them are connected to a 1987 graphic poster by Lanny Sommese. In Sommese’s famous graphic of social commentary (the poster advertised a rape hot line), the torso, thighs, and upper arms of a woman’s body (which is cut off at the neck) are shown in a state of vulnerable display (see figure 1.3). It is not clear whether the figure is lying down or standing, but the placement of the arms (spread out) seems to indicate a prostrate position of forced submission; it is depicted as a body under violent sexual attack might be visually portrayed.

The film poster differs in two very specific ways from this poster: the figure in the Precious poster is fragmented beyond and across the lines produced by the foreign hand, and despite this extensive fracturing she is still standing. It is even possible that she is in a process of moving, walking forward even though her body is literally in pieces. In Sommese’s image, the proximity to the body refuses the viewer’s desire for voyeuristic distancing and thus the intimation is that the viewer is this close to sexual violence. As a victim? A perpetrator? A witness? However the viewer encounters this image, they cannot escape the violation on display. They cannot step back from it, as is possible with the Precious poster, since the distance and the assumed fragility of the woman is literally standing in the way of the viewer’s capacity to encase the image with its totalizing effect. With the Precious poster there is no this close, no intimate proximity of viewer and voyeur. The hand seems superhuman—it is larger than the scale of the hands on the woman’s body—and contributes to the concept of distancing. Sommese’s handprint belongs to a figure emerging from below, its origin either exposed or obscured by the body parts that do not appear in the poster (lower legs, feet). In the movie poster for Precious, the larger-than-scale hand also comes up from below, but this below is different. Reminiscent of the hand of that ubiquitous movie villain Freddie Krueger, this alien hand is climbing out of the ground below.

With horizontal as well as vertical severing, the figure assembles and reassembles the form of visual engagement (a spreading apart and a coming together) so that the fullest measure of violation on display is muted. She seems to be at the juncture of an invisible mechanical apparatus that has just recently quartered (or sixteenthed) her corpus with the assistance of the otherworldly hand emerging from the ground. For the viewer to negotiate the bifurcated homage (or violated homage), they would have to be equally engaged in both the arts/graphic universe of Saul Bass’s cinematic advertisements and the social/political interventions Lanny Sommese’s work created. Without these very specific reference points, the viewer is left with a sense (via the enlarged hand) of concealed corporeal horror alongside the triumphantly capable survival of this gendered body (and who is more buoyant than black women in the national imaginary?).

Thus, the clear victimization of the scene Sommese’s illustration portrays is betrayed here, since it is not an image of dissection (as in Preminger’s film) and it is also not a clear social commentary on the evils of sexual violence. Instead it lodges itself between the spectral currency of the circus poster and the utter ridiculousness of an autopsy performed on a living person. This is the spectacle of a multilayered cultural production: an anonymous silhouetted black woman’s body, portioned and possessed by an alien hand, is presented to the viewer as an offering that does not indict him.8 The poster functions as a commentary on black female sexual subjectivity that does not take that subjectivity seriously. Instead, it plays on those familiar tropes of race and gender, further producing the handprint of hegemony on an already fragmented surface. The handprint is therefore part of the riddle. Is the woman’s body broken or triumphant? Are we looking at a cartoon or currency? We will never know. And as long as we do not know for sure, we do not know at all. The crowded metahistory of black women’s representational subjection is well documented. It is important, though, that we look at Precious as the intended analog to a fraught and contentious politics of representation. As Peggy Phelan writes, “Seeing the other is a social form of self-reproduction, for in looking at/for the other, we seek to represent ourselves to ourselves. As a social relation the exchange of gazes marks the failure of the subject to maintain the illusionary plentitude of the Imaginary.”9 The Precious poster thus not only enables the viewer to “see the Other” but also presents him with a potent modality of race and gender through the imagery of a fractured black female body. How do you feign interest in a throwaway body and a throwaway gender? You shred it to pieces and see if that has the desired effect.

The burnt-orange Precious poster shatters, it literally fractures and shreds to pieces, black women’s long-fought battles to reclaim their bodies. Turning the delineation of traumatic physical and sexual violence into a maddening display of the carnivalesque, the graphic opens out into a world where black women’s corporeal vulnerabilities are as illegible as the face on the silhouette. The poster offers a free-for-all for the eye—a gaze unencumbered by questions of subjectivity, by requirements of empathetic engagement. The distanced centering of the body affords the viewer this double positioning: the viewer remains invisible to the subject and can gaze at (or visually assail) the available body at will, while feigning concern about black women’s sexual and literal lives. Because the image lacks corporeal specificity, the viewer engages with a form that implies a body in pieces but never encounters Precious. And so this irony splinters the scene: a chopped and fragmented figure, ingloriously broken, has the name that indicates a loved possession and the integrity of familial protection. The definition of the adjective (valuable, beloved, adored) does not fit the figure in the image. Here the viewer gets to participate in ironic subjectivity: a dead walking body that is also a valued and loved human being. Since the graphic borders on the ridiculous (and we can return here to the earlier allusion to the carnival), its cartoonishness distances the viewer. In other words, it is a refusal of engagement.

Writ Large: Broad Brush Strokes and the Faceless Form of Supplication

Another poster for Precious is different in several significant ways. Instead of a silhouette, it presents a mock painting illustrating a close-up of a faceless figure that is obese and darkened to the point of pitch-blackness (see figure 1.4). The figure is cut off right below the waist and is created out of broad and loose brush strokes, so the viewer encounters form but no face and is therefore unable to engage with the personhood of the figure. There is literally no there there—no one with which to concern oneself. In bell hooks’s analysis of spectatorship of the black female body in films, she notes the strategies black women have used to ameliorate the violence of what is taking place on the screen. “Conventional representations of black women have done violence to the image,” she writes. “Responding to this assault, many black women spectators shut out the image, looked the other way, accorded cinema no importance in their lives.”10 Unfortunately, black women’s criticism of the film industry has not been met with a serious attempt to represent their lives and dimensions on the silver screen. Precious joins a mélange of recent movies that have placed black women (and the many types of violations of black women) at the center of the performance of social-cultural engagement. Consistent only in their misapprehension, these representations seem to ignore black feminist criticism and concern that has attempted to draw attention to the issue of who gets to tell a black woman’s story.11 Black women in films are seen as always already sexual beings, and they are seen through the vehicle of a visual medium that shreds, diminishes, and mutes them.12

In this second poster for Precious, the pattern of misapprehension gathers in the center of the image, where the title of the film and its protagonist are featured on a nameplate necklace draped around the neck of the figure (see figure 1.4). This figure’s existence has been smudged out. There is no face, no eyes, and thus nothing to elicit concern or connection. The frame of her ...