![]()

CHAPTER 1

Coffeehouse Babble

Smoking and Sociability in the Long Nineteenth Century

Ganko’s kafene was, as usual, filled with noise and smoke. It was the meeting place of old and young alike, where public matters were discussed, and the Eastern Question too, as well as all the domestic and foreign policy of Europe. A miniature parliament one might say.

—Ivan Vazov, Under the Yoke

Awash in smoke and sociability, Ganko’s kafene is the fictional social hub and main setting for the most widely read Bulgarian novel, Ivan Vazov’s Under the Yoke (Pod Igoto). With Vazov as guide, the reader experiences Ganko’s social panorama, its parade of archetypal characters from a Balkan mountain town in Ottoman Bulgaria who drink bitter coffee, ruminate and debate, laugh and observe, within a “dense fog of tobacco smoke.”1 Set in the period before Bulgarian political autonomy, Ganko’s has an air of political excitement. On the canvas of the kafene Vazov skillfully paints a late Ottoman landscape—the months leading up to the April Uprising of 1876—rife with social change. Indeed, in Under the Yoke Vazov portrays a time of upheaval in which generations, ways of life, and political objectives collide head on, noticeably between the kafene walls. Yet in spite of this ferment, the kafene and the surrounding Balkan towns strike the reader as somehow timeless; stagnation is the subtext to the impulse for change.

The social life of tobacco in Bulgaria’s long nineteenth century is virtually inseparable from the life and times of the kafene. Slavic-speaking Christian, or “Bulgarian,”2 men had traditionally gathered in the alcohol-imbibed krŭchma (tavern), but over the course of the century they began to enter the “sober” social life of the kafene. Already a centuries-old Balkan Muslim tradition, the kafene was a new phenomenon for Balkan Christians, a portal to a new world. Facilitated by the ritualized consumption of coffee and tobacco, the discovery and invention of “Bulgarianness” took place, at least in part, amid kafene conviviality. Smoking and sipping coffee in the kafene (and later in the European café) became intimately connected to Bulgarian upward mobility; to their increased authority in Ottoman villages, towns, and cities; and for many, to a national and political awakening.3 The changing clientele of the Balkan kafene to a large degree mirrored the dramatic changes in Bulgarian society in the long nineteenth century.4

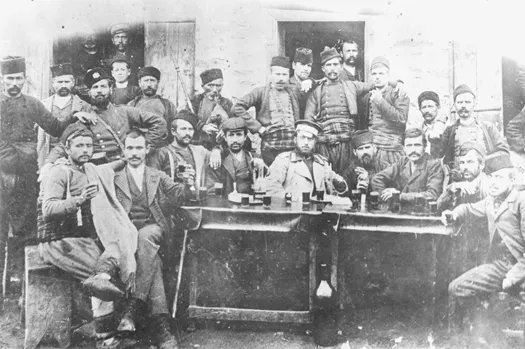

Bulgarian men at a traditional krŭchma in the Plovdiv region, date unknown. Courtesy of the Regional State Archive in Plovdiv.

Patterns of tobacco consumption both reflected and drove new modes of political organization and cultural identification, particularly inside privileged smoking venues like the kafene. Smoking, in a sense, was connected to Bulgarians’ initiation into a broader world of commerce, politics, and urban culture that took on a decidedly European hue over the course of the century. It is tempting to map this story through the familiar paradigm of “Europeanization,” which so often shapes understandings of this period in both Bulgarian and Ottoman-Balkan history.5 Certainly the penetration of European ideas, material culture, social mores, and a range of institutions was an important aspect of change in the nineteenth-century Balkans. This was especially true after the Crimean War (1853–56) and the momentous Russo-Turkish War (1877–78), in which Bulgaria gained autonomy and de facto independence from the Ottomans. Western commerce, consular and missionary activity, and the travels and studies of Bulgarians abroad brought an avalanche of influences, and the kafene was an important conduit. But an emphasis on Europeanization offers a rather false and value-laden teleology of change that belies the complexity of the Bulgarian introduction into a world of smoking and sociability. For many Bulgarians, their entrance into kafene culture was entirely local or connected to work and travel to Ottoman towns or cosmopolitan port cities. Of course, Bulgarian merchant colonies abroad were also exposed to European café culture, but Ottoman kafene culture in Istanbul and the Bulgarian provinces was the most readily available coffeehouse experience.

Significantly, the Ottoman coffeehouse was the original model for ritualistic coffee and tobacco consumption in Europe, imported and appropriated into early modern culture along with other Eastern “pleasures.”6 Over the centuries its shape and aesthetics evolved in various contexts, subjected to a range of both laudatory and critical appraisals.7 And while the café drew scrutiny, European observers also projected onto the Ottoman kafene their own doubts and anxieties about idleness and lax morality at home. Western visitors seemed preoccupied with the coffeehouse and Ottoman smoking habits. For most, the patterns of Ottoman Muslim leisure were emblematic of idleness, decadence, and degeneration. Yet others viewed the Bulgarian shift from the drunken krŭchma to the sober kafene as a positive phenomenon. Idle as it may have seemed, the kafene was a presumed improvement for drunken and “subjugated” Christian men.

Western appraisals of local vices were voiced just as increasingly decadent forms of Western leisure culture were making their way into the Ottoman and post-Ottoman realm. These both seduced and repelled Bulgarians, who saw them as either pleasurable or as a perceived threat to Balkan national cultures and mores. Some were attracted to Western impulses of “moral uplift,” while others saw such notions as fundamentally foreign and patronizing, attached to invasive Protestant missionary efforts. In short, Bulgarian kafene and smoking culture evolved in the midst of a simultaneous embrace and rejection of various elements of Western leisure culture and normative values. In addition, because smoking and kafene culture were both local and broadly cosmopolitan, they could be embraced as intimately native or rejected as deeply foreign.

By the late nineteenth century, Bulgarian smoking had become a constant in a rapidly transforming world of commerce, politics, leisure, and sociability. Whether associated with sobriety in the kafene, or inebriation in the krŭchma, Bulgarians learned to smoke amid profound shifts in Ottoman and Western smoking practices. As Bulgarian smoking increased, so too did anti-Ottoman and anti-western sentiments influence newly articulated critiques of smoking and leisure, and the broader project of defining boundaries of national culture and public morality. Embraced or reviled, smoking had carved a permanent place for itself in the Bulgarian social world while undeniably playing a role in the rapid transformation of that world.

Aghast and Titillated: The Western Gaze

The history of nineteenth-century Bulgarian smoking is difficult to unearth. Given the paucity of sources, the voluminous writings of the travelers, missionaries, and other Westerners who crisscrossed or settled in the region are worth exploring. Here they are employed not just as empirical supplements but as a reminder that the Bulgarian kafene and smoking culture did not unfold in a vacuum. By the nineteenth century, the Bulgarian coming of age—embedded in a world of smoke and social interchange—was taking place in a highly fluid late-Ottoman world, amid foreign observers and participants. It goes without saying that these memoirs and travel writings were deeply biased, though such biases are far from uniform. Instead they reveal significant contradictions and shifts in Western attitudes toward Ottoman and especially Bulgarian leisure and consumption practices.

Competing narratives of fascination, revulsion, condescension, and criticism have left behind a rather mixed legacy. The layers, inconsistencies, and significance of such writings have only begun to be untangled.8 On the one hand, Western observers most often defined the Balkans or “European Turkey” as part of the Orient. But the presence of separate Christian and Muslim populations complicated this picture.9 An analysis of nineteenth-century Anglo-American observations of leisure and consumption in the Ottoman lands seriously muddies the clarity of dichotomous constructions of the “Orient” and “Occident,” or any notion of a distinct “Balkanness.”10

As one might expect, the smoking “Turk”11 perpetually titillated Anglo-American observers as a central trope in their exotic image of the Ottoman East. For example, in her memoirs, Fanny Blunt, the British consul’s daughter (and later wife of another consul), says of the perpetually smoking Turk, “his cup of coffee and his chibouk contain for him all the sweets of existence.” She speaks wistfully of the kiosks along the Bosporus, in which a “range of sofas runs all around the walls on which the Turk loves to sit for hours together lost in meditation and in the fumes of his indispensable companion the narghile [hookah].”12 In the Ottoman lands, the chibouk (a long pipe) and narghile were the preferred forms of smoking paraphernalia until later in the century, when they were gradually displaced by the cigarette. The narghile in particular was an object of Western fascination, a central prop in European images of nineteenth-century Ottoman life. Its supple, curvy, almost womanly form—and its long (vaguely phallic) tube for sucking—undoubtedly seduced Western consumers. Numerous photographs and paintings from the period featured men posed in a coffeehouse or in front of mosques, next to a narghile or the long, slender chibouk.13 “Harem” women—probably paid prostitutes or lower-class women—were also posed against the narghile for maximum effect.14 The market for pictures of the “real” Orient, however, coincided with a period when numerous travelers complained that Ottoman authenticity was presumably being spoiled by “foreign” influence. Indeed, by the 1860s the narghile was already on its way out, eclipsed by the hand-rolled cigarette, though the chibouk proved more persistent.

At the same time “authentic” Eastern pleasures continued to be packaged and appropriated for consumption in Europe (and the United States), even as they became the subject of pointed critique. A recurrent theme in virtually all European travel writings in the nineteenth-century Ottoman Empire was the image of the Oriental as a “sensual and lazy being ‘doing nothing.’”15 In a variety of works, Western travelers were seemingly baffled by the presumed immobility of Balkan Muslims, “whose only delight was to sit day after day in a coffee house sipping his coffee, smoking his pipe and fiddling with the beads of the tesheh [worry beads].”16 The Turk’s seemingly prevalent forays into Eastern kayf (pleasure seeking) appeared to many the polar opposite of the reputed industriousness of the West.17 This image of the decadent smoking Turk was to a large degree a reaction to changes within economically and militarily ascendant Western society, with its relatively newfound cult of sobriety and industriousness.

Certainly by the early nineteenth century, Western assessments of leisure and consumption had become normative if not explicitly political. The Oriental penchant for pleasure and idleness, while seductive, was ultimately seen as indicative of Ottoman decay and decline.18 As the Scottish-British novelist and trader John Galt (1779–1839) argued, if one kept in mind Ottoman “idleness and constant use of the pipe,” then it was “not absurd to argue that tobacco brought down the Ottoman Empire in the same way that gun powder maintained it.”19 The image of the idle Turk in a cloud of smoke in fact, seemed to explain the Turkish inability to bring order to the increasingly violent and disorderly Balkan world. As the British diplomats and travelmates Stanislas St. Clair and Charles Brophy described in their Residence in Bulgaria, based on observations from the late 1860s, “the Zaptiehs [Ottoman police] prefer their coffee and cigarettes at their guard house to scouring the countryside in search of brigands.”20 In the same vein, they maintained that “at the Sublime Porte functionaries give you a cup of coffee, a chibouque, and an evasive answer,” further lamenting that they don’t seem to want to “civilize,” which would mean they would have to “trade in their cafés for prisons.”21

Yet St. Clair and Brophy employed such imagery not to demonize but to undermine the image of the “terrible Turk” lording over the “innocent” Balkan Christian. American and British Protestants, among others, had propagated the latter image, intent upon drawing support for their missions among the reputedly innocent and industrious Bulgarians. In contrast, St. Clair and Brophy maintained that the Balkan Christian peasant was “morally and physically degraded and idly lies dead drunk upon a dung-heap” and hence was better off under Ottoman rule.22 St. Clair and Brophy’s image of the drunken Bulgarian was one of many images that resonated in the pantheon of Western travel writings and memoirs on European Turkey.23 Prevailing assumptions about alcohol and Christian moral degradation seemed to offer an explanation for the Balkan political and cultural predicament. The Bulgarians were, after all, Christian and technically a European people, yet they had been subject to Muslim Asiatic rule for five centuries. The idle Turk was at least sober.

Christian drunkenness, in fact, was a driving force behind the nineteenth-century civilizing missions undertaken by Anglo-American missionaries in the eastern Balkans. By midcentury the explicit focus of American and closely associated British Protestant missions to the Ottoman lands was on the “nominal Christians” or “degenerate churches” of Eastern Orthodoxy who seemed most in need of “moral renovation.”24 Concurrent with the rise of British and, more slowly, American commercial and diplomatic interests in the region, missionaries flooded the Ottoman lands with the desi...