![]()

SIX

Blowout Part I

“We need to do something dramatic like Watts,” I thought to myself following the riots in Los Angeles. I, of course, didn't support violence, but Watts showed me that only when minorities rebel or publicly resist in such a way to bring attention to their grievances would the rest of society listen. The problem affecting Mexicans in the L.A. schools was so severe and so damaging to our kids that some kind of explosion was needed. I didn't know what this would mean. All I knew was that without some kind of mass protest by the students nothing would change.

It was about this time that my father paid one of his rare visits from Mazatlán. I had not been very close to him over the years, but he was, after all, my father. One day, during his visit, I told him about all of the problems in the schools and how frustrated I was and how I felt this weight on my shoulders to do something about it. But what?

“Huelga,” he calmly said to me. “Huelga.”

“What do you mean, huelga? You mean a strike?”

“M'hijo [son], you know that after I went to Mazatlán, I helped to organize the railroad workers. You know that I was thrown in jail for this. But it was only by striking that the workers got changes for themselves. That's the only power that poor people have, to organize and go on strike.”

“Huelga, strike?” I later thought about what my father had said. “But how would this work with the kids? They're not going to strike. What do they do? They go to school and don't leave or not come to school? How do we work this?”

The Chicano Movement

All this started me thinking about a plan of action, a strategy that could successfully be applied to the schools. I knew for sure that a mass action was needed—something like a strike—but the actual plan was something I started formulating in my mind for the next couple of years. In the meantime, things were happening in the Chicano community that in different ways inspired me and the students to seriously consider something big. For one, there was the example of César Chávez and the farmworkers. In 1965, César led the farmworkers to strike against grape growers in the San Joaquin Valley. This was the beginning of the Chicano Movement, at least in the rural areas. Those of us in the cities began to hear and read about César. We supported the Mexican American farmworkers in their struggle to achieve dignity and better economic conditions. My family was not of this background, but I could sympathize ethnically and politically with César and the campesinos (farmworkers) and their fight in the fields. When César staged the impressive march to Sacramento from Delano, the union's headquarters, in the spring of 1966, I very much wanted to participate but couldn't. I'm sure that this dramatic action also inspired my thinking about what to do in the schools.1

I met César for the first time at a MAPA (Mexican American Political Association) meeting in 1965 in Riverside. I had recently joined the group and decided to attend its convention at the Mission Inn. I hadn't realized that César and the farmworkers would be there as well. As I went to a general session on a Saturday morning, all of a sudden I see these guys with red flags with the union's eagle in the center enter the hall shouting “Huelga, Huelga, Huelga! [Strike, Strike, Strike!]” Then this little guy—chaparrito—gets up and starts talking about the strike. It was César. He wasn't a heavy rapper, but in his quiet and modest way, he exuded a tremendous spirit of commitment and strength. “Damn,” I thought, “these guys are organized!”

Although I never visited Delano, I supported the later boycott of grapes and encouraged my students to do likewise. I allowed literature on the boycott to be distributed in my classroom. I didn't bring it in, but some of the kids did. Not many of our students that I can recall actually participated in the boycott, but they were becoming aware of it and of César.

I think that the impact César had on me was that it made me realize his struggle was predominantly in the fields and that his main constituents were farmworkers. That was understandable. This was his fight. But he wasn't talking about people working in factories, sweatshops, and other places where Mexicans worked in the cities and lived in much larger numbers. Somehow the struggle had to also involve the urban barrios. This influenced my thinking about a dramatic action in the schools. There had to be an urban counterpart to César's agricultural struggle.

It was also at this time around 1966 and 1967 that I began to hear about other Chicano struggles. I read about the movement of Reies López Tijerina in New Mexico and his struggle to regain the lands of the poor Hispanos. His fiery, evangelistic, and charismatic image made him into an instant media figure. So I knew about him and that this was still another Chicano fighting for his people and bringing awareness to the issues by staging dramatic actions. Then there was Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales in Denver, who also began to organize young Chicanos. I could more readily identify with Corky because of his urban struggle, including targeting the schools. Both Tijerina and Corky spoke in L.A. when early Chicano students at campuses such as UCLA invited them. I didn't attend, but I knew that they were having an impact.2

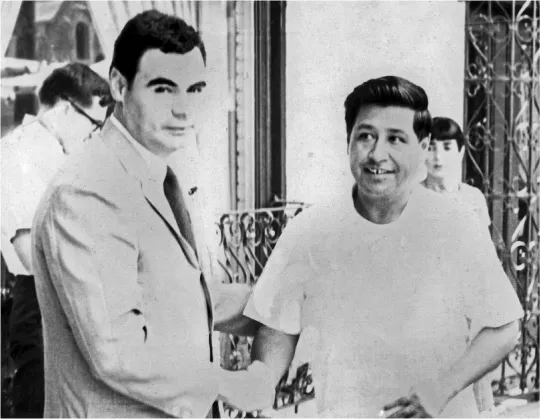

Sal Castro and César Chávez, Riverside, California, 1965. Courtesy Sal Castro Personal Collection.

Because by 1967 there were a few more Chicano college students at UCLA, USC, L.A. State, and East L.A. College, some of whom I knew because they were Lincoln graduates, such as Moctesuma Esparza, but also Al Juárez, Carlos Muñoz, and Carlos Vásquez and others from other high schools, I first began to talk about a serious action in the schools with them. I met with some of these college kids to try to get some of them to volunteer to come back to the schools to help the high school students to read better. As I met with them, I bounced my ideas about the need for something to happen. They responded positively. As products of these schools and survivors of them, they knew the problems and that things couldn't go on as usual.3

The Piranya Coffee House

I expanded on my thoughts when some of the college students and a group called Young Citizens for Community Action (YCCA) formed after the 1967 Hess Kramer conference and, led by Vicki Castro and David Sánchez, started the Piranya Coffee House on Olympic Boulevard and Atlantic on the east side. They rented an old abandoned warehouse. Ironically, today it's the site of a fancy Latino restaurant called Tamayo's. I served on the first board of directors of the Piranya, along with Father John Luce, Episcopalian priest from the Church of the Epiphany in Lincoln Heights, who was very active and supportive. They needed adults to help sign for the lease.4 In those days, everyone had a bohemian coffeehouse, which had been the influence of the earlier beatnik movement of the late 1950s and early 1960s. These coffeehouses were the precursors of Starbucks. Young people sat around drinking coffee and having long intellectual conversations or hearing poets read their stuff. I knew both Vicki and David because both had attended one of the Camp Hess Kramer conferences and were impressive young people. As a result of their experiences at the conference, they became more political.

What also politicized them and some of the others who attended the Piranya was that kitty-corner to it was a highway patrol substation. The officers didn't like young Chicanos congregating right across the street from them. It rubbed them the wrong way to see a bunch of Mexicans out there having a good time. They probably thought these Chicanos were trying to be white. So they started harassing them, going into the Piranya, including raiding the place in the guise of looking for drugs. A few of the kids had pot, but it was not a big-time deal that warranted the harsh and rough tactics of the highway patrol and also the county sheriffs. This harassment had the effect of making the students and young people not only more political, but militant. The YCCA, as a result, became transferred into the Young Chicanos for Community Action, or more popularly known as the Brown Berets. In fact David, as the prime minister of the Berets, and the others made me an honorary Brown Beret.5

Despite the problems with the police, the Piranya became a central meeting place for many of the young Chicanos who became activists in the Chicano Movement in L.A. As they became more involved, they invited various political speakers. I think César Chávez spoke, as well as black radicals such as Stokeley Carmichael. They asked me to speak. I talked about the need for a mass action in the schools and I encouraged them to help when it came. I knew even then that if it came to such a protest I would need the college students and the Berets to help with the younger kids. They were developing leaders and I would need them. I concluded by saying: “Hey, stay tuned, because we're going to do something. The kids are going to do something in the schools and we're going to need your help.”6

PAULA CRISOSTOMO, student at Lincoln: “The Piranya was a fun place for those of us still in high school to go to without our parents around. It attracted kids from all the Eastside schools, so we had an opportunity to meet and share experiences. I'd go on Saturdays either in the afternoon or early evening after getting my parents’ permission. The Piranya was called a coffeehouse, but it didn't serve coffee. In fact, nothing was served. It was one large room with some big round tables and chairs and a radio and record player.”7

Pocho's Progress

I was further motivated to organize the students at Lincoln and possibly other Eastside schools after I read an article in Time magazine in its April 28, 1967, edition. It shocked and angered the hell out of me. It was called “Pocho's Progress”—about Mexicans in East Los Angeles. In the first place, the piece used the term pocho, which in some circles is considered to be a pejorative term suggesting a Mexican American who has lost his/her culture. Second, the article didn't discuss any progress made by Mexican Americans. Instead, it consisted of one stereotype after another. It was racist. Among other things, the writer described East L.A. in these negative words: “Nowhere is the pocho's plight for potential power more evident than the monotonous sub-scab flatlands of East Los Angeles where 600,000 Mexican Americans live. At the confluence of the swooping freeways the L.A. barrio begins. In tawdry taco joints and rollicking cantinas, the reek of cheap, sweet wine competes with the fumes of frying tortillas. The machine-gun-patter of slang Spanish is counterpointed by the bellow of lurid hot-rods driven by tattooed pachucos.”8

Son of a bitch, that's how he described us. I remember talking to some of the college students about this and asking them, “Is this you?”9 But what also pissed me off was that no Mexican American leaders appointed or elected seemed offended or complained. Upset, I went to a meeting of the Mexican American Chamber of Commerce on the east side, and none of the speakers, including this popular radio show guy by the name of Pepe Peña, mentioned the Time article. I stood up and said: “Don't you people read? Didn't anyone see that racist article in Time about us? Aren't you angry about this? It's an insult to the whole community. Goddamn it! What's it going to take for some of you to do something?”

The article and the passive reaction by community leaders only convinced me that there was no going back. If the adults couldn't or wouldn't lead, then the kids would.10

Camp Hess Kramer

In preparing for this mass action by the public high school students, there is no question that the Camp Hess Kramer conferences during the 1960s and especially the 1967 one became the backbone for what was to come. Some of the high school students who attended the conferences and then went on to college were the same college students that I would rely on to help me. Some of the high school students who attended the conference in 1967 and returned for their senior year at the Eastside schools would become leaders in putting together the action.

At all of these conferences, the students continued to share their grievances about the schools. All of them were similar to the conditions at Lincoln. Each conference revealed a growing political and ethnic consciousness among the kids. They began to use the term “Chicano” more and more. This awareness came as a result of their common experiences and the dialogues that went on at the camp. They began to talk about the black civil rights movement, about César Chávez and the farmworkers, and about the Vietnam War. I, as a counselor, encouraged these discussions. I did so not only with my group, but as I table hopped and talked with other students. I also continued to talk about what I did with my Lincoln students concerning about being proud and aware of their ethnic roots and culture, about the history of Mexico and of Chicanos, all these things that they didn't hear in their schools.11

The college conference counselors also played a crucial role in this conscientización (conscience building). They were becoming very political and even militant themselves. The conference gave me more opportunity to talk about my ideas with the college students. They were ready to go. Whatever I was going to say, it didn't take much to convince them. By 1967 they had learned about the free speech movement at UC Berkeley and about the anti–Vietnam War protests. They knew about the black freedom marches in the South. They wanted to be in on the action. “How come we haven't done something like this?” they would ask me. They were ready and willing to go, and they helped me socialize this attitude to the high school kids.

The 1967 conference was especially notable because it reflected more and more the politicization of the students, both college and high school. By this time, I was openly discussing with the students the possibility of a dramatic action in the schools. I could see that this appealed to many of them. This growing consciousness was captured in a TV documentary, Today, Not Mañana, by KTLA, Channel 5 in Los Angeles. Clete Roberts, a well-known and respected TV reporter, requested permission to do a piece on the conference. We had no problems with this and felt that this would give the conference greater recognition and publicity. Roberts especially focused on capturing some of the dialogue between the kids and their conference counselors and some of the kids’ comments at our general session.

Some complained about their school counselors: “They assume you can't take anything more than homemaking and family planning.”

One girl said: “How can we as Chicanos find out who we are when our textbooks label Pancho Villa as a criminal?”

And still another girl asserted a developing Chicano Movement theme that came to be called internal colonialism: “When you say we came to America, that's not right because America came to us—we Mexicans were here first.”

Impressed by the passion and discontent expressed by the students, Roberts concluded his report by saying: “The main impression we bring back is that of a mood of impatience, a growing sense of urgency. The young Mexican American is tired of waiting for the Promised Land. As one of them told us: ‘It must be today, not mañana.’”12

Many years later, I was pleased to hear some of our former Camp Hess Kramer students and counselors reflect on what they gained at the conference that motivated them to participate in protesting school conditions. One of the counselors, Vicki Castro, who went on to be elected to the L.A. school board, remembers, “I think that this was the first I have any memory of seeing on a big scope that what I was experiencing in school was happening all over, and to a h...