![]()

1: Sangamentos

Performing the Advent of Kongo Christianity

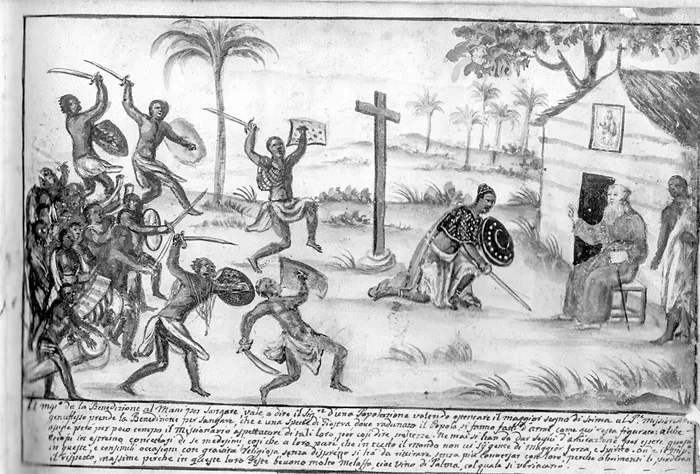

A vociferous crowd of men armed with swords and shields march across an open plaza toward a modest church (Figure 2 [Plate 1]). The beat of a long drum, the chime of a marimba, and the blow of two ivory horns orchestrate the group’s acrobatic steps. In rhythm, the bare-chested dancers swing large swords, raise shields of different shapes, shout out loud, and flash wide-open eyes in an awesome display of strength and determination. At the head of the group, a richly dressed man kneels in the shadow of a monumental cross. He wears a mpu cap enhanced with a red feather, a long crimson coat embroidered with a white design, a nkutu shoulder net, a colorful wrapper, and rows of anklets. He holds in his hands a European-looking sword and a shield, as do the other dancers. Down on one knee, he pays his respects to a Capuchin friar quietly sitting in front of the church, giving his blessing to the assembled men. Next to the priest, a mestre, a church leader and interpreter for the friar, watches the dancers while holding the attributes of his office, a long staff and a white cloth loosely wrapped on his left arm. Above the two men, overlooking the scene, is a painting of the Virgin pinned on the building’s facade and a cross attached to the church’s rooftop.

In this lively watercolor, painted around 1750, the Capuchin Bernardino d’Asti depicts the impressive staged assaults of the sangamento, a prominent performance that gave rhythm to public life in the kingdom of Kongo. The word sangamento is a lusitanism derived from the Kikongo verb ku-sanga, itself stemming from the widespread Bantu root càng, meaning “to be pleased.” The Kikongo-language dictionary “Vocabularium Latinum, Hispanicum et Congense” (written circa 1650) recorded the term as cuangalala (plural yangalele) in translation for both the Latin exultare and gaudere, meaning “to rejoice.” French missionary Jean-Joseph Descourvières similarly defined the word in his 1775 dictionary of the northern dialect of Kikongo as “to jump or leap alone or in a crowd with certain prescribed gestures in manifestation of joy or congratulations,” a definition that captured the characteristic moves and mood of the dance. In the Christian Kongo, sangamentos served dual purposes. On the one hand, they acted as preparatory martial exercises for soldiers and as demonstrations of might and determination in formal declarations of war. On the other hand, they accompanied joyful celebrations of investiture, complemented courtly and diplomatic pageants, and lent their pomp to pious celebrations on the feast days of the Christian calendar. During the dances, the sitting king or ranking ruler, members of the elite, and common soldiers each took the stage in order of precedence. With spectacular simulated assaults, feints, and dodges, each man showcased his dexterity with weapons and his physical agility and asserted his place in the kingdom’s political hierarchy. The fake but awe-inspiring ritual assaults were the occasion for members of the elite to reinforce their prestige by inviting—and theatrically defeating—challenges to their power.1

FIGURE 2 Bernardino d’Asti, The Missionary Gives His Blessing to the Mani during a Sangamento. Circa 1750. Watercolor on paper, 19.5 × 28 cm. From “Missione in prattica: Padri cappuccini ne Regni di Congo, Angola, et adiacenti,” MS 457, fol. 12r., Biblioteca Civica Centrale, Turin. Photograph © Biblioteca Civica Centrale, Turin

Sangamentos existed in central Africa before European contact and remained a widespread practice into the twentieth century within and beyond the boundaries of the Kongo. The kingdoms of Loango to the north and Ndongo to the south also staged their own variants of the ritual. With the advent of Catholicism at the turn of the sixteenth century, the Kongo sangamento evolved in form, nature, and purpose. New choreographies, regalia, and weapons in the dances reflected the broad changes to the kingdom’s political and religious life brought about by its participation in the religious, diplomatic, and commercial networks of the Atlantic world. The dances can thus be used to consider the mythological, religious, and political redefinitions that allowed the Kongo elite to reinvent the nature of their rule in this new context. Sangamentos and their visual and material symbolism illustrate how the rulers of the kingdom employed mythology and its visual and material manifestations as generative spaces of correlation within which they merged and transformed Christian lore and central African tradition into a novel Kongo Christian discourse.2

The Two Parts of the Sangamento

Friar Girolamo Merolla da Sorrento described sangamentos in the late seventeenth century as performances staged in two parts. In the first act, the dancers dressed “in the way of the country,” wearing feathered headdresses and using bows and arrows as weapons. In the second act, the men changed their outfits, donning feathered European hats, golden crosses, necklace chains, knee-length strings of corals, and red coats embroidered with gold thread. They also traded in their bows and arrows for firearms, imported weapons echoing the European-style swords depicted in the 1750 watercolor. Merolla noted plainly the binary structure of the performances he observed, but sangamentos often intertwined the two parts rather than clearly delineated them. The watercolor in Figure 2 (Plate 1), for instance, captures the event in a manner that both stresses and merges the two sides. In a didactic, synthesized depiction, it collapses the two moments of the ceremony into a single scene but maintains a marked distinction between the two in the spatial arrangement of the figures. The left side of the vignette focuses on Kongo elements, while the right side of the image, beyond the threshold of the monumental cross, presents a scene anchored in Christian attitudes and symbols. In spite of this arrangement, central African regalia figures prominently in the Catholic blessing and European-style swords in the Kongo dance. Fundamentally, the image emphasizes how the two parts of the sangamento seamlessly articulated disparate objects, symbols, and practices into a meaningful, coherent whole.3

The correlation of heterogeneous parts at the core of the Christian era’s sangamentos reflects the operations through which the Kongo elite created a novel Kongo Christian myth of the origins of the kingdom that drew from and redeployed both Catholic and central African lore. The early part of the show staged the founding of the kingdom—centuries before the advent of Christianity—by Lukeni, the original civilizing hero of the Kongo’s creation myth. Accordingly, primarily local regalia and weaponry that symbolized central African notions of might and prestige appeared in the first act. King Nzinga a Nkuwu used similar props in a sangamento he led in 1491 before the advent of the Christian era. According to oral tradition, Lukeni, a young foreign prince of extraordinary military skill, leaves his homeland north of the Kongo, marches south with an army of followers, and conquers the lands of his future kingdom in a great military feat made possible, the narratives suggest, by his command of iron technology, until then unknown to the people of the southern shore. In addition to military skill and iron smelting, he brings to the Kongo new wisdom that forms the basis of the kingdom’s organization.4

The subsequent performance in the sangamento, in which the dancers appeared in a mix of local and foreign attire, referred to the second founding of the kingdom in 1509 by Afonso, son of Nzinga a Nkuwu and first great Christian king of the Kongo. According to oral histories recorded in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Afonso was an early supporter of Catholicism and ascended to the throne after a bitter battle against one of his brothers, who, in contrast, opposed the new religion. As noted previously, wars of succession were common in the Kongo, where the crown was not hereditary but was bestowed by a group of electors upon one of a number of eligible nobles. Afonso, with the help of the miraculous apparition of Saint James the Apostle leading an army of horsemen, and under the cross of Constantine that appeared in the central African sky on his behalf, was able to defeat his brother and win over the Kongo to Catholicism. The second act of the performance featured insignia and emblems inspired by both central Africa and Europe. Dancers appeared in what had become the characteristic regalia of the Kongo Christian elite, an intricate mix of swords, mpu caps, crosses, nkutu shoulder nets, imported coral necklaces, and European cloaks. No longer were they simply powerful heirs to Lukeni’s feat; they were also mighty Christian knights emulating the example of their first Catholic king. Merolla himself suggests in his description the link between the dances and the second founding, explaining that the kingdom’s main sangamento takes place on the feast day of Saint James as a tribute to the holy warrior that helped secure the victory for Afonso.5

Creation Myth of the Christian Kongo

The creation myth celebrated in the second part of the sangamento originated from a series of letters Afonso wrote around 1512 to the elite of his kingdom. Thirty years after the arrival of Europeans on the central African coast and twenty years after the baptism of his father, Nzinga a Nkuwu, as João I in 1491, the young monarch lived in a world with rapidly expanding horizons. Since the first landing of Portuguese explorers and clerics on Kongo shores in 1483, a sustained flow of people, objects, and ideas circulated and wove ties between the Kongo and Portugal. In the early decades of contact between the two realms, selected Kongo youth traveled to Lisbon, where they received a formal European Christian education; Portuguese clerics, merchants, and craftsmen, on the other hand, sojourned in central Africa to practice their trade. The exchange emerged from the Europeans’ interest in the Kongo as a commercial partner. In the words of explorer and chronicler Duarte Pacheco Pereira, writing around 1506, they sought copper, ivory, “beautiful” and “peerless” raffia-palm cloth, and “some slaves in small quantity.” After the baptism of the central African king, Portugal could also boast that the Kongo was a Christian ally and shining proof of the successes of their overseas proselytizing efforts. Reciprocally, the Kongo elites found in their relationship with the faraway land a source of new wares, technologies, and philosophies that they selectively welcomed according to their own aesthetics, needs, and curiosity. Intrigued at first by a range of novelties, they soon dismissed the ones they deemed unfit for their needs, such as European farming techniques, and received others, such as textiles and clerics, with great enthusiasm. In this context of rapid change and broad experimentation with novelties, Afonso formulated and promoted, in letters addressed to the kingdom’s elite, the story of his rise to power as the second founding of the Kongo.6

The correspondence presented a narrative that performed a symbolic reformulation of select elements of Kongo history and Christian lore that allowed Afonso to naturalize Christianity into a central African phenomenon while simultaneously inscribing his kingdom in the larger realm of Christendom. The new king intended this story to become the official narrative of his accession to the throne and of the advent of Christianity in the Kongo. The letters explained how he, oldest son of king Nzinga a Nkuwu, had been among the first in the Kongo to champion the new faith. After the death of his father, he dutifully traveled with a small retinue of professed Christians to the capital of the kingdom, Mbanza Kongo. European Christian rules made the crown rightfully his as firstborn son of the deceased ruler; Kongo law, however, only saw him as one of several eligible successors. The people of the capital, led by his brother Mpanzu a Kitima, who refused conversion, thus took up arms to oppose his presumptous plans. Overpowered in the ensuing battle and soon on the verge of defeat, Afonso and his companions shouted out to Saint James the Apostle as they rallied for the final and surely fatal assault. At that very moment, against all odds, enemy lines broke in panic. As the few survivors in the brother’s faction later explained, an army of horsemen led by Saint James himself appeared in the sky under a resplendent white cross and struck scores dead.7

The letters also encompassed a core visual dimension. One of them included a painting, now lost, of the new coat of arms of the kingdom of Kongo that Afonso presented to and interpreted for his vassals. The king of Portugal, as a gift to his overseas counterpart, had commissioned the arms from a Portuguese herald who based his work on a written account of the battle that Afonso had sent to Europe in 1509. The African king’s narrative directly inspired the design of the coat of arms, which strikingly differed, for example, from the plain blazon that a Wolof prince received upon his baptism in Lisbon in 1488. Unlike the elaborate Kongo escutcheon, the emblem presented to the west African man merely featured a generic golden cross on a red background surrounded by a border of Portuguese blazons that did not encode any complex cross-cultural reflection between the herald and the Wolof prince. Afonso might have directly requested the coat of arms in the now lost 1509 letter, but, regardless of the origins of the design’s commission, he presented its adoption as his own decision in later correspondence. “It seemed to Us a most deserved thing,” he wrote, “that, in addition to the many graces and praises we give to Our Lord … we would keep the record and memory of such a clear and obvious miracle and complete victory in our [coat of] arms, so that the kings that will follow Us in our kingdom and lordship of the Kongo would not be able at any time to forget such great grace and favor.”8

The escutcheon, depicted in António Godinho’s 1548 Portuguese manuscript armorial, formalized Afonso’s story of accession in the typically European format of heraldry (Figure 3 [Plate 2]). Following the African king’s own reading detailed in the letters, the arms show a silver cross on a chief azure above a red shield that respectively memorialize the luminous apparition of the cross in the central African sky and the bloodshed of the battle. On either side of the cross, two sets of scallop shells stand for Saint James, “whom We called upon and who helped Us,” alongside a battalion of knights, represented in the shield by five armored human arms, each brandishing a sword. The two-one-two placement of the swords, derived from the arms of Portugal, should be read, the Kongo king specified, as a reference to the five wounds of Christ. At the bottom, the escutcheon of Portugal itself, featured as Kongo’s benefactor and ally, accompanied two “idols” broken at the waist. The 1548 armorial gives a full version of the arms, complete with a gold helm facing left, appropriately crowned as a royal emblem. A crest of five sword-car...