![]()

PART ONE

Lived Experience

![]()

Spending six years in the madrasas of India has unalterably shaped my experience of Islam as both an intellectual tradition and a practice. After pursuing journalism, political activism, and academia, I found a deeper appreciation of my complex formation in the madrasas.

CHAPTER ONE

A Novice

Mumbai, still known as Bombay in 1975, was a bewildering city for an eighteen-year-old young adult from Cape Town, South Africa. Nothing prepared me for the intimidating throng of beggars and street urchins outside the airport, the countless people sleeping on sidewalks, and the city’s heavy monsoon air and strong odors. At the time, I wasn’t aware of the full impact of the “state of emergency” that Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had imposed to silence her critics, but I knew that fear surrounded me: people whispered about danger and secret arrests. But there was a bigger fear that engulfed me. As much as I was enthusiastic to learn about Islam, the faith I had inherited from my parents, my first glimpses of India made me fearful. What was I doing there? I suddenly understood my father’s reluctance to let me go to study religion in India.

Deciding to study in India began with a crisis of faith precipitated by an attack on my religion in high school in Cape Town, South Africa. I was barely sixteen when a classmate, a Jehovah’s Witness, brought some stinging anti-Islamic literature to class. I still hear my fellow student Gabriel saying, “Muhammad was an impostor, who spread his message by the sword and was unworthy of being a prophet.” And he added, “Actually, Muhammad cribbed his teachings from Jews and Christians whom he met during his travels.” At the daily after-school religious sessions—also called “madrasa” in South Africa—I had learned that as a youth, the Prophet Muhammad traveled to Syria with his uncle. During one such journey he met a friendly Christian monk who, in a peculiar way, anointed him as a prophet, according to Muslim tradition. But never did I suspect the Prophet of treachery. This first exposure to the hostility some Christians harbor toward Muslims crushed my innocent and fragile sense of faith. But the encounter also allowed me to think critically about Islam: it changed my life.

A trip to the library in Cape Town did little to reassure me. The refined prose of Western authors like Sir William Muir and Montgomery Watt recycled the same charges against Muhammad and skewered Islam’s claims to authenticity. On reflection, it seems rather odd that as devout Christians and rational Scotsmen, Muir and perhaps less so Watt found it plausible that God could be incarnate in a man from Nazareth, but adamantly denied that a seventh-century Arab could proclaim prophecy as did the Jewish prophets.

I found comfort in the circles of a group called the Tablighi Jamaʿat. The Arabic word tabligh means “to convey or transmit.” The Tablighi Jamaʿat’s mission was to remind Muslims of their religious duties and how to be devout. I attended their study circle at my neighborhood mosque in District Six, Cape Town’s multiethnic and defiant cultural center where I lived during the school week. Several years later, apartheid’s architects would obliterate District Six in order to disprove the possibility of the coexistence of different races. We were assigned to racially segregated ghettoes.

But questions about my faith persisted. My religious doubts—and my existential anxiety as a person of color in a white supremacist world—became unbearable. My plans to become an engineer slowly gave way to another obsession. I wanted to go to India to study the faith of my ancestors, to reconcile that faith with my gnawing demands to understand faith within the idiom of revelation, reason, and science. My mother was sympathetic to my cause, but my father didn’t want to see his eldest son turn out to be a poor cleric dependent on the benevolence of the community and with diminished life prospects.

At the time, Dad, who had been born and raised in South Africa, was not really observant, giving priority to his business. He relented to my plans, though, when my aunts cajoled him and reminded him of the noble standing of learned scholars of Islam and the Qurʾan and the promise of paradise awaiting their benefactors as well.

In my heart I was following my mother’s prayers as I confronted the challenges of student life in India. She had come to South Africa as a nineteen-year-old bride from the state of Gujarat. Far from close relatives and burdened with domestic chores in an extended family with seven children, one of whom died in infancy, she took refuge in religion. In particularly tough times she would share with me, her eldest, the religious lore she learned in her childhood in the village of Dehgaam, of how the Prophet Muhammad’s daughter, Fatima, endured life’s trials.

My grandiose plan to study Islam, however, was also an escape from the drudgery of life in South Africa: the third-rate segregated schools, where discipline was dictatorial, violence the norm, and education poor, and the weekends and vacations spent in backbreaking work in the family grocery store in the Strand, a seaside town thirty miles (48 km) away from the main metropolitan city, Cape Town. I was aware of the country’s segregationist politics. I knew little of the lives of the majority of black South Africans and only fully recognized their plight following the Soweto uprisings of June 16, 1976, after I’d been in India just more than a year.

NINETY DAYS

I had agreed to spend four months in the Tablighi Jamaʿat before entering a madrasa. A brainchild of an Indian cleric, Muhammad Ilyas (d. 1944), who felt the teachings of Islam were not reaching the grassroots faithful in British India, the Tablighi Jamaʿat has no real bureaucratic administration, but its presence is felt in almost every corner of the globe. Resigning from his teaching position at a prestigious madrasa, Ilyas devoted himself, against tremendous odds, to revival work (daʿwa) in the Mewat in the 1920s, a region straddling the two states of Rajasthan and Haryana. He used a small mosque, the Banglawali Masjid, as his base in Delhi, where he cultivated his core of loyal associates. On the same site today in the Delhi suburb of Hazrat Nizamuddin, a spartan mosque serves as the international center (markaz) of the Tablighi Jamaʿat, an explicitly nonpolitical piety movement that incorporates elements of Islamic spirituality (Sufism). It is important to note that the Tablighi Jamaʿat is broadly affiliated with the Deoband school founded in the late nineteenth century but differs radically from more radical offshoots of this highly diverse Deobandi theological formation that will be discussed later in this book.

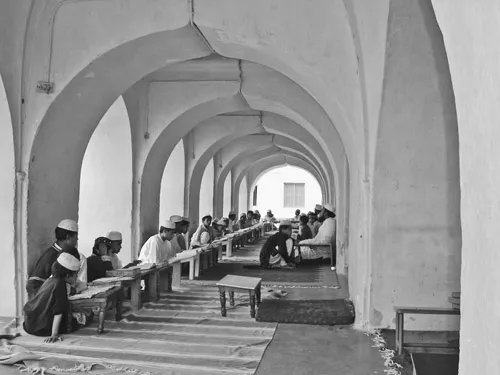

Young male students memorizing the Qur’an at a mosque in Srirangapatna, in Karnataka State in India. Memorizing the Qur’an is done at the elementary level of madrasa education. (Picture: Prakash Subbarao)

Ilyas had a simple but highly effective evangelical message boiled down to “six points” to supplement the observation of Islam’s five cardinal pillars of practice: make sure Muslims grasp the true meaning and implications of the creedal statement that “there is no deity, except Allah and that Muhammad is His messenger”; pray conscientiously five times a day; acquire learning and engage in the frequent remembrance of God; honor fellow believers; adopt sincerity in all actions; and participate in missionary work (daʿwa) by spreading awareness of Islam. The Tablighi Jamaʿat now hosts some of the largest Muslim gatherings, involving millions of participants on the subcontinent and around the world.

Working with the Tabligh was a grueling ordeal with a steep learning curve, and overcoming the inevitable cultural shock of passing my days in India was daunting. We slept on the floors of mosques, ate simple meals, navigated treacherous roads, and traveled in overcrowded trains. By the lights of my naïve faith, eternal damnation awaited these millions of Hindus apparently devoted to idols. In just weeks, India taught me to ask the first and most enduring question about the workings of divine justice: how was it possible that a just God could promise me paradise . . . and damn all these people who look like me? Years later, I would discover that many thinkers in the monotheistic tradition were confronted by similar questions, including the eleventh-century thinker Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (d. 1111), about whom I would later write a book. Ghazali too struggled to understand why only some people would be saved and not others. In the end, he found solace in spiritual experiences and the intuitive truths of mysticism.

I cut short my planned four months with the Tablighi Jamaʿat to three and headed for the Madrasa Sabilur Rashad in Bangalore along with two other South Africans I met in the Tabligh. At the austere, walled campus, I found dozens of students apart from the majority South Indians and the few from my home country—young men from Trinidad and Tobago, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the United States and a lone Cuban. I occupied the fourth thin mattress in a sparse and cramped dorm room with a West Indian, an African American, and the Cuban. In pursuit of piety, the latter two would rise at 3 A.M. for optional prayers and liturgy, tormenting the rest of us for not doing the same. I already witnessed in the Tablighi Jamaʿat a grating notion of piety, which to my mind was like a “calculator mentality” and now it was even more evident in the attitude of some of my fellow students. Some of my roommates were not only preoccupied with attaining afterworldly rewards for performing certain acts of piety but they also celebrated their outlook.

Daily madrasa routine in Bangalore would begin at least an hour before sunrise with preparation for the early morning prayers. Afterward students remained at the mosque to read designated portions of the Qurʾan. Others used the auspicious early morning hours to memorize the Qurʾan, known as hifz. Breakfast would follow in the dining hall, called the mess, a stark reminder that the British once ruled India. Breakfast consisted of South Indian idli (steamed savory cakes made of lentils and rice), a crispy roti (baked bread), and chai (tea boiled in milk). Most foreign students made breakfast in their rooms with a spread of eggs, some toast, and chai.

I had arrived at the madrasa only one month before it closed for the long Ramadan break, the end of the academic year. But in that short time I chafed at the highly regimented and pietistic environment, and worst of all, the abysmal cafeteria food. I took a class on memorizing portions of the Qurʾan for liturgical purposes and perfecting my recitation of the holy book. The six-hour day of memorization was tedious, and students would take frequent bathroom breaks, sip lots of tea, and play surreptitiously to pass the time. The memorized passage for the day and the back lessons were recited to an instructor at least twice in a day. It takes two or three full years to memorize the entire Qurʾan fluently. Not having budgeted such a length of time, I selected chapters that would be useful in delivering sermons and for liturgical purposes. Later in life it turned out that knowing the Qurʾan intimately was an asset for instructional purposes. Since all instruction was in Urdu, I also threw myself into learning both Urdu and Arabic in private lessons.

But after almost four months in India, I had yet to enroll in an ʿalimiyya program required for gaining the knowledge and skills of an ʿalim, the Arabic word for “a learned person.” The plural ʿulama, meaning those learned in the religious disciplines, is the generic term used today to refer to Muslim clerics. So while madrasas were on vacation, I spent the Ramadan break with my maternal grandparents, visiting my parents’ ancestral villages in Gujarat near Bharuch, a bustling city on the banks of the Narmada River. On the outskirts of Bharuch I fortuitously discovered a small madrasa (seminary), Darul Uloom Matliwala, supported by an affluent South African family, which at the time enrolled some 200 students.

The centerpiece of the seminary was a three-level Parsee bungalow. Parsees are followers of Zoroastrianism, an ancient religion of Persia. They straddle Indian a...