![]()

Step 1: Selecting Behaviors

Advice is what we ask for when we already know the answer but wish we didn’t. Erica Jong

Whether you are developing a program to promote water efficiency, waste reduction, watershed protection, energy efficiency, modal transportation shifts, or virtually any other area related to sustainability, you will encounter the same problem— there is a multitude of behaviors that may be targeted. In the case of energy efficiency, we might encourage home owners to add additional insulation to their attics or wash their clothes in cold water. We might encourage employees of local businesses to turn off their computers when not in use, or have farmers sell their produce at local markets. These are just a few of the many energy-efficient actions that might be promoted. Since it is common to have a variety of behaviors that we might foster, it is important to be able to make informed choices regarding which are the most worthwhile to target.

Imagine that you are assigned the task of designing a program to encourage energy efficiency. More specifically, your program is being funded to reduce CO2 emissions through more efficient energy use. The first question that you will want to ask is, “Which sector makes the most sense to target?” In Canada, non-transportation related energy use is a follows: industrial (55%), residential (23%), commercial/ institutional (18%) and agriculture (3%).1 If you were delivering your program in Canada you would understandably gravitate toward those Canadian sectors that have the largest energy use. In considering these sectors you might elect to focus on residential energy use as this sector uses a significant amount of energy. In addition, you know of a number of organizations that you can partner with to target this sector more effectively. Having decided upon the sector, your next task is to evaluate which behaviors within this sector are worth promoting.

To determine which behaviors to promote, begin by creating a list of residential energy efficiency behaviors. Note, however, that an Australian project found that there were over 200 behaviors related to residential energy efficiency.2 While the number of residential energy efficiency behaviors is vast, don’t be surprised if lists for other domains (e.g., water efficiency, transportation, conservation) are also sizable. Since we are understandably interested in those behaviors that can have a substantive impact upon energy use, it makes sense first to determine if some areas of residential energy use are more important than others. If this is case, we may be able shorten our list by focusing our attention on those areas that account for the most significant energy use.

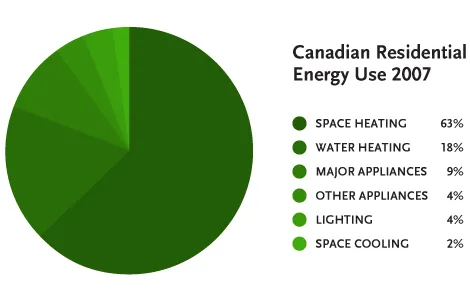

As the following chart demonstrates, Canadian residential energy use differs markedly by end use.3 Given its northern climate, the largest share of residential energy use is for space heating (63%), followed by water heating (18%) and then major appliances (13%). Collectively, these three categories account for 94% of Canadian residential energy use. Interestingly, the two categories that traditionally receive significant attention in Canadian energy efficiency programs, lighting and air conditioning, use relatively little energy—4% and 2%, respectively. Knowing that space heating, water heating and major appliances dominate Canadian residential energy use suggests the order your most impactful behaviors are likely to follow. Without additional research you won’t know which behaviors within these categories are most impactful, for example adding additional insulation to the walls of a home versus installing energy efficient windows, but you will have greater confidence that your behaviors are drawn from the most important categories.

Once you have determined which categories of energy use are most important, you are ready to begin creating your list of behaviors. Each behavior that you list should be guided by two criteria: no behavior should be divisible; and each behavior should be end-state. Both are described below.

DIVISIBLE BEHAVIORS: Divisible behaviors refer to those actions that can be divided further. For instance, many residential energy efficiency programs encourage adding additional insulation as a way to reduce home energy use substantially. However, adding additional insulation to a home can be further divided into adding insulation to the attic, the external shell (walls), or the basement. Why does it matter that a list of residential energy-efficiency behaviors specify adding insulation to attics, walls and basements rather than just adding additional insulation? Each of these behaviors differ substantively in the barriers that are associated with them. I recently added insulation to our attic to improve the energy efficiency of our home and reduce its CO2 footprint. This was a fairly simple process that involved a contractor blowing additional insulation into our attic. Completing the task took the contractor several hours and was relatively inexpensive. In contrast, adding additional insulation to the external shell of our home involved substantial cost, time and effort. First, our existing siding had to be removed. Our house was then wrapped to reduce heat loss, additional insulation was added over the house wrap and, finally, our home was re-sided. The renovations to the external shell of our home took over a month. While the renovations to our attic and the shell of our home both involved adding insulation, they differed dramatically in their associated barriers. Since the barriers to sustainable behaviors are often behavior-specific, it is critical to begin by listing behaviors that are non-divisible. Failing to do so will leave you with categories of behaviors in which the behaviors that make up a category (e.g., adding insulation to a home) may differ dramatically in their associated barriers and benefits.

The divisibility of behaviors needs to be carefully considered. Adding additional insulation to an attic, for example, is also divisible. We need to specify whether it will be a contractor or home owner who will install the additional insulation, as well as the type of insulation to be installed. Why does this matter? In Canada, there are two primary forms of insulation that homeowners add to their attics: fiberglass batts and cellulose fibre. In the case of fiberglass batts, either a home owner or a contractor would purchase the batts from a hardware store and then add the additional insulation to the attic. However, blowing cellulose fibre into an attic is significantly more challenging for a home owner than it is for a contractor.

Contractors who blow insulation into attics tend to have vans that are outfitted for this purpose. In the back of their van they will have a motor for blowing the insulation as well as several hundred feet of hose that can reach from a driveway to an attic. For a home owner to blow insulation into their attic they would need to rent the blower and hose and have a vehicle that was large enough to carry these, and the insulation, back to their home. In addition, they need to know how to use the rented equipment. Clearly, the barriers to a home owner blowing insulation into their attic are substantially higher than for having a contractor do the same work. As a consequence, a list of residential energy-efficient behaviors would distinguish between whether a contractor or home owner was blowing insulation into an attic. Similarly, this list would also distinguish between whether a contractor or a home owner was adding fiberglass batts to an attic. At this point you might be thinking that community-based social marketing is rigid in its approach to selecting behaviors. It is, but for good reason. Failure to create a list of non-divisible behaviors will jeopardize the development of effective strategies as there will be insufficient information regarding the barriers to specific behaviors.

END-STATE BEHAVIORS: In addition to your behaviors being non-divisible, you also need verify that they are end-state. End-state refers to the behavior that actually produces the desired environmental outcome. For instance, the purchase of compact fluorescent light bulbs or the installation of programmable thermostats are not end-state behaviors. Our principal interest is not in having homeowners purchase compact fluorescent light bulbs, but rather in having them install them.† Similarly, our principal interest is not in having homeowners install programmable thermostats, but rather in having them program them. Frequently, environmental programs encourage prior behaviors and fail to achieve the end-state behavioral changes that matter. To determine whether a behavior is end-state, simply ask: “Will engaging in this behavior produce the desired environmental outcome, or will the target audience need to do something else before the desired outcome is achieved?” If they need to engage in another behavior before the desired environmental outcome is achieved, you have not selected an end-state behavior.

Having created a list of non-divisible, end-state residential energy efficiency behaviors drawn primarily from the categories of space heating, water heating and major appliances, your next task is to compare these behaviors to determine which are worth promoting. This involves analyzing the following three characteristics of each behavior: 1) How impactful is the behavior? 2) How probable is it that my target audience will engage in the behavior? and 3) What level of penetration has the behavior already obtained with my target audience?

DETERMINING IMPACT

Two methods exist for determining the impact of the listed behaviors. The first, and preferred method, involves collecting information. Remembering that in our hypothetical example, your program is being funded to reduce CO2 emissions, you would need to assess the emission reductions that are associated with each of the residential behaviors you have listed. For example, you would collect information on the emissions associated with such diverse behaviors as installing and configuring a ...