eBook - ePub

Stroll

Psychogeographic Walking Tours of Toronto

Shawn Micallef

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 312 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Stroll

Psychogeographic Walking Tours of Toronto

Shawn Micallef

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Stroll celebrates Toronto's details at the speed of walking and, in so doing, helps us to better get to know its many neighbourhoods, taking us from well-known spots like the CN Tower and Pearson Airport to the overlooked corners of Scarborough and all the way to the end of the Leslie Street Spit in Lake Ontario.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Stroll als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Stroll von Shawn Micallef im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Social Sciences & Urban Sociology. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Thema

Social SciencesThema

Urban SociologyThe Middle

Yonge Street

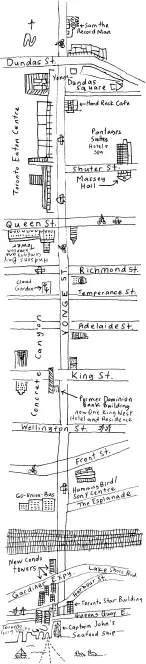

| Connecting walks: Harbourfront, Nathan Phillips Square/PATH, YMCA, Dundas, St. Clair, Eglinton, Finch Hydro Corridor, Sheppard, Downtown East Side. |

Towards the end of high school – circa 1992 – four of us from Windsor got into a Dodge Shadow and drove up the 401 to Toronto for our first real road trip. We didn’t know much about Toronto other than the tourist places like the CN Tower or Casa Loma – neighbourhood names like the Annex, Rosedale or even Kensington Market had only a faint ring of familiarity – but we knew the first place we had to go was the Yonge Street strip. We parked, we walked back and forth and eventually we were served drinks at a second-floor bar, staring in awe into the giant rotating neon discs of Sam the Record Man. We were in the promised land.

If you’re from a small town or a car-dominated city like Windsor, your initial moments along Yonge are made up of all the big-city clichés: crowds of people, amusements, stores open late into the evening and Swiss Chalet restaurants next to sex-toy shops. And though you can still see wide-eyed tourists taking it all in the way we did that first time – the most euphoric of them ready to throw their hats in the air like Mary Tyler Moore did when she moved to Minneapolis – Yonge Street isn’t what it used to be. In fact, it’s a little boring, and poking around the history of this stretch might leave you wishing for a return to the days when Toronto presented a big-city show, long before it ever worried about being world class.

Despite being this city’s main street, and though it holds a mythic place in the Canadian psyche, Yonge occupies a strange place in our imagination. We all know it’s important, but we often ignore it. It’s not the main shopping street anymore. The seedy bars are seedy in the wrong way. And nobody really calls Yonge home. Yet when the city needs to come together, it comes here. This is where a million people gather for the annual Pride parade, and it’s the only place to go when a sports team wins – if the Leafs ever do win the cup, the street will likely burn to the ground from the heat of all that pent-up fan adrenalin. But perhaps most telling of its importance to Toronto are events that, nearly thirty years apart, came to symbolize our collective anxiety about being a big city.

Yonge starts right at Lake Ontario. It’s an inauspicious beginning for such a mythical street – at least it is right now, as this part of the waterfront is in flux, and has been for a while. To the west are the condos – some new, some old – that Torontonians often complain about. To the east lies the post-industrial Port Lands landscape, which we also complain about, a place where decades of unfulfilled plans have bred a waterfront cynicism into the city that we’re slow to shake, even as development appears imminent.

Still, there are spectacular attractions, like Captain John’s floating seafood restaurant, which is docked in the harbour at the very foot of Yonge Street. Should you venture onto the ship, you’ll find a surf-and-turf cocktail-lounge time warp of tuxedoed waiters and deep-fried foods. The ship itself is a relic from the former Yugoslavia. The restaurant’s owner, Captain John Letnik, sailed the ship to Toronto in 1975 after purchasing it from the Yugoslav government for $1 million. He put it up for sale in 2009, so it may yet see the high seas (or lake) again.

If you look along the sidewalk here, in front of the ship, you’ll see a short metal balcony that extends over the water and lists the distances to various Ontario towns on the ‘world’s longest street’ – it reminds me of the directional sign that pointed to other cities in the movie version of M*A*S*H. Though Yonge’s longest-street claim is challenged by some, as you stand here, looking north, it’s a good way to feel connected to the rest of the province on a street that everybody knows about.

Yonge’s first hundred metres are wide and, though the parking lots that languished for years here are being filled in with new buildings, it is still a frumpy start – or end – to a main street. The Gardiner, just to the north, always blamed for cutting off Torontonians from our waterfront, is being consumed by condo towers on both sides. The raised expressway isn’t exactly disappearing, but it is becoming just another part of this landscape rather than the dominant view. Once underneath the much longer railway underpass, Yonge rises up to the original shoreline of Lake Ontario and crosses what is now Front Street. Here, at the southeast corner, is the Sony (née Hummingbird, then O’Keefe) Centre, a perfectly modern performance venue designed by the late Toronto architect Peter Dickinson.

Between Front and Richmond streets, Yonge is a concrete canyon. Day trippers returning from the Toronto Islands on the Ward’s Island ferry can get a wonderful glimpse of it from the water. While no longer a particularly interesting pedestrian experience – much of the on-street retail and human energy has, as with much of the financial district, disappeared into the underground PATH tunnels – One King West catches the eye as it rises out of the former Dominion Bank Building. The original 1914 structure serves as a plinth for an impossibly razor-thin, fifty-one-storey condo tower that slices through the downtown sky like a schooner. As impressive as it is, though, it’s a subtle part of the skyline. From many angles, it’s just a nondescript part of the familiar clump of downtown buildings, so its narrow form can surprise when viewed from the north or south.

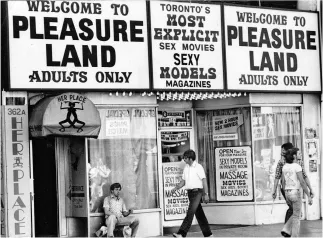

‘The Yonge Street Strip’ – the part that matters to Newfoundlanders and Windsorites alike – runs roughly from Richmond Street up to Wellesley Street. In its glory years, it was what the internet is to us today: a place where sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll are just a step away from all things moral and upright. What made it magnificent is that it all played out in real time, in real space.

This Midnight Cowboy Toronto included places like Mr. Arnold’s, ‘Canada’s adult entertainment centre,’ which boasted uncensored stag movies for $2, or $1 for seniors. In 1971, the Toronto Star reported on the Catholic Church’s concern that ‘sex shops and pornographic bookstores are destroying Toronto the Good.’ In fact, it was first- and second-hand knowledge of Yonge Street’s tawdry spectacle, the one you can see if you watch the Canadian cinema classic Goin’ Down the Road, that made the notion of ‘Toronto the Good’ a bit of a mystery to me for years.

Toronto’s tolerance for this activity ended in July 1977, when twelve-year-old Emanuel Jaques, a Yonge-and-Dundas shoeshine boy, was raped, drowned in a sink full of water and ultimately dumped onto the roof of 245 Yonge, just south of where the Hard Rock Café is today. The clean-up of the street that followed grew bigger than originally intended, eventually leading to a moral panic and a gay witch-hunt that reached its peak with the infamous bathhouse raids of 1981.

Those raids had a galvanizing, Stonewall-like effect on Toronto’s gay population, which had long been concentrated along Yonge north of College Street. Many of Toronto’s early gay bars were located here, including the St. Charles Tavern at 488 Yonge (a former fire hall that today sports a refurbished Victorian clock tower) and the Parkside Tavern at 530 Yonge (now a twenty-four-hour Sobeys). It had long been a Toronto tradition for mobs of people to gather by what is now the Courtyard Marriott hotel to, heckle the drag queens as they moved from the Parkside to the St. Charles each Halloween night. Many came just to watch and enjoy, as people do on Church Street now, but violence was never far away. In 1968, police found several gasoline bombs behind the St. Charles and, by 1977, a 100-officer-strong police square was needed to control spectators who tossed insults, bricks and eggs.

The Yonge Street strip in 1973 in all its smutty, exciting glory.

Yonge was decidedly queerer than the rest of the city, and it was also wetter. This is where Toronto the Good’s lapsed Presbyterians came to drink, at places like the Silver Rail at Yonge and Shuter Street, which opened in 1947 as one of Toronto’s first licenced cocktail lounges. Half a block south, a three-lot strip on Yonge facing the Eaton Centre is strangely derelict, at odds with its ornate and storied past. At 197 Yonge stands the dirty and fenced-in former Canadian Bank of Commerce building, built in 1905. Just north, at 205, you’ll find the former Bank of Toronto, built in 1905 by E. J. Lennox (of Old City Hall and Casa Loma fame). Between them, there’s a park disguised as a forbidding vacant lot. If you’re feeling particularly romantic, the small raised ‘stage’ area can be viewed as an homage to the Colonial Tavern that once stood here. On the Colonial’s stage, jazz greats from Gillespie to Holiday to Brubeck played in surroundings so intimate people could chat with the performers by the stage after the show. Years later, in a basement space dubbed the Meet Market, notorious Toronto punk pioneers the Viletones further eroded Toronto’s morals just as their contemporaries in New York did at CBGB.

So where have you gone, Yonge Street? Walking along, it’s hard to find a drink in reasonable surroundings, and the good bands and djs don’t play here anymore. The centre of the strip now would appear to be Yonge-Dundas Square, probably the most controversial bit of real estate in the city. Everybody, it seems, has something bad to say about it, but I’m not sure why. At most hours, and when the square isn’t being rented out for a private function (a valid criticism of the management of the space), it’s full of people enjoying themselves and watching the fountains or whatever performance is going on. Surrounding it is our very own vulgar display of electric power, which takes the form of walls of advertising. On humid nights, the air glows hundreds of metres into the sky around the square, as if filled with electrified neon. While it may not be to everyone’s particular taste, it’s helpful to view Yonge-Dundas Square as a shock-and-awe commercial pressure release, where anything can and will go. Just as long as it doesn’t spread to the rest of the city, we can enjoy it for what it is. Many of us already appear to be doing so.

Though Yonge-Dundas Square’s beloved/unbeloved status is in flux, almost everybody can agree that 10 Dundas East – the building on the northeast corner of the intersection, formerly known as ‘Metropolis,’ and as ‘Toronto Life Square’ after that – isn’t inspiring in its architecture or interior design. At one of Toronto’s most visible locations, an entirely appropriate place for movie theatres and stores, the view from Yonge-Dundas Square looks straight into the heart of a dowdy Future Shop utility corridor on the second floor. Watch as employees make their way from a pair of washrooms to their break room, which is littered with cheap folding chairs and tables.

Another long-time anomaly sits at the northwest corner of Yonge and Gerrard. Though home to one of Toronto’s most unfortunately prominent parking lots, plans are underway to build ‘Aura,’ a ‘supertall’ condo, here. Development has been a long time coming to this parcel of land. The Great Depression has been over for nearly three-quarters of a century, yet this lot has languished since then, when economic collapse thwarted the Eaton family’s empiresized dreams for the location. The Eatons opened their flagship store at the north end of this block in 1930, and while still a magnificent example of art moderne architecture, it was just one part of a bigger plan to build the largest office and retail complex in North America. The downturn nixed plans for a thirty-six-storey Empire State Building–style tower, and the surrounding land was filled with unsympathetic structures and, eventually, parking. If you happen to find yourself in the seventh-floor Carlu – the streamlined reception and concert hall where Lady Eaton lunched and Glenn Gould liked to play – check out the huge architectural model on display and see what could have been. And though some may lament the Winners discount store that has moved into the main shopping hall downstairs, it’s closer to the Eatons’ mass-retailing, something-for-everybody ethos than anything that has been in this space since Eaton’s vacated the site when the Eaton Centre was opened in 1977. Though Toronto derives its name from an Iroquois word, Tkaronto, which means ‘place where trees stand in the water,’ examples of First Nations public art around the city are rare. One giant exception is found in the atrium of the former Maclean-Hunter building at College and Bay streets, one of Toronto’s more ‘unsympathetic’ structures, depending on your sensibility. The plain glass tower’s basement houses the Three Watchmen, three totem poles (one fifty feet tall, the other two thirty feet) by artist Robert Davidson of the west-coast Haida Nation. Maclean-Hunter may not exist anymore (it was subsumed into the Rogers empire), but Davidson’s contemporary totems mark the day in 1984 when a Canadian print media company was mighty enough that could afford its own skyscraper.

North to Bloor, Yonge is a jumble of shops and restaurants without a particular identity. Perhaps that’s the fate of a main street: it must represent the whole city so it becomes a kind of pastiche of other neighbourhoods. For a change, take the Yonge passage, which runs parallel to the street just a few steps east between Bloor and Wellesley stations. A serie...