eBook - ePub

Portraiture and Photography in Africa

John Peffer,Elisabeth L. Cameron

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 472 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Portraiture and Photography in Africa

John Peffer,Elisabeth L. Cameron

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Beautifully illustrated, Portrait Photography in Africa offers new interpretations of the cultural and historical roles of photography in Africa. Twelve leading scholars look at early photographs, important photographers' studios, the uses of portraiture in the 19th century, and the current passion for portraits in Africa. They review a variety of topics, including what defines a common culture of photography, the social and political implications of changing technologies for portraiture, and the lasting effects of culture on the idea of the person depicted in the photographic image.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Portraiture and Photography in Africa als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Portraiture and Photography in Africa von John Peffer,Elisabeth L. Cameron im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Art & African Art. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Thema

ArtThema

African ArtEXCHANGE

PART ONE

1. Portrait Photography:

A Visual Currency in the

Atlantic Visualscape

JÜRG SCHNEIDER

African historians’ interest in photographic sources is still rather recent and can be traced back to the mid-1980s. Today, after more than twenty years of research, we know the general outlines of the history of African photography, but have yet to move beyond the larger picture.1 In looking closely at some centers of the early history of West and Central African photography, such as Sierra Leone, Fernando Po, and Gabon, as well as at the professional careers of African photographers such as Francis W. Joaque, this essay will contribute to a better and deeper understanding of the early history of West and Central African photography. Particularly, it will show how portrait photographs served within what I term the “Atlantic visualscape” as a visual currency thus allowing “facework between absentees” in an increasingly globalized context.2

The Atlantic Visualscape

The long contact between the Western world and Africa and hence between different cultures and continents, which intensified in the sixteenth century, created a space where images of all kinds circulated, were produced, and were consumed. Within this area of interaction Africans came in contact with drawings, oil paintings, lithographs, lantern slides, engravings in illustrated newspapers, illustrated books, and eventually photographs. For instance, during the reign of Queen Victoria (who, like her husband Albert, was an early enthusiast of photography) portraits of the Queen and the Royal Family were printed, painted, and engraved on various materials and came to be omnipresent throughout the British Empire.3 Evidently the appropriation of the West’s visual repertoire and practices did not occur without mutual misunderstandings, as the following incident shows: “When some natives took Catholic images brought to [Cuba] by Columbus’s men, buried them in a cultivated field and urinated on them in order to produce a rich harvest, the Spanish responded by burning the offenders to death.”4 However, many other sources point to a natural integration of the new images into Africans’ visual practices. According to the British trader John Whitford, King Eyo from Creek Town (near Bonny in the Niger Delta) had a portrait of Queen Victoria taken from the illustrated newspaper The Graphic hanging in his house.5 The prevalent habit of African elites of hanging up pictures of all kinds was also noticed by the French medical doctor Griffon de Bellay in the Gabon hinterland as early as 1862.6 Europeans and Americans in Africa and at home, at the same time, became acquainted with masks, sculptures, patterns, and drawings on cloth, walls, and bodies. Few, but quite illustrative, sources provide hints as to the practice of exchanging photographs in a way similar to how business cards are given to business partners today.

The concept of the “Atlantic visualscape” draws on the seminal works of scholars such as Arjun Appadurai, Paul Gilroy, Deborah Poole, Marie Louise Pratt, and Anthony Giddens.7 All of them point to the importance of considering an extended space—geographically, socially, politically, and economically—as a “contact zone” where a multitude of ideas, artifacts, and people circulated.8 Gilroy’s concept of the Black Atlantic is well known and since its introduction in the early 1990s has triggered an ongoing thread of critical and fruitful discussion. Deborah Poole introduced the terms “image world” and “visual economy,” with which she sought to capture the complexity and multiplicity of the realm of images that we might imagine circulating among Europe, North America, and Andean South America.9 Appadurai, by undertaking an approach to a general theory of global cultural processes, employed a set of terms (ethnoscape, finanscape, technoscape, mediascape, ideoscape) to stress different streams or flows along which cultural material may be seen to be moving across national boundaries. Both Poole and Appadurai underline the simultaneously material and social nature of vision and representation which situates the Atlantic visualscape at the intersection of materiality and discourse.10

FIGURE 1.1. John Parkes Decker, Street in Freetown, 1869 or 1870. The photograph shows rows of freshly planted trees in the streets of Freetown. The image was included in the Photo Specimen Book of the Missionary Leaves Association. COURTESY OF CHURCH MISSIONARY SOCIETY, LONDON.

In her book Imperial Eyes, Marie Louise Pratt argued that travel reports “gave European reading publics a sense of ownership, entitlement and familiarity with respect to the distant parts of the world that were being explored, invaded, invested in, and colonized.”11 The ideas expressed by Pratt can be broadened into two directions: first, by including all potential readers, not only Europeans, within the Atlantic visualscape, and second, by merging them with Benedict Anderson’s notion of imagined communities which emerged from the very activity of “reading,” or rather, for our purposes, “seeing things together.” This in turn takes us back to Appadurai, who underscored the new role for the imagination in social life, as well as to Deborah Poole, who pointed to the photographic image as a medium which “helped to shape feelings of community and sameness among metropolitan bourgeoisie, aspiring provincial merchants, and upper- and middle class colonials scattered around the globe.”12

Finally, Giddens, without specifically mentioning the visual in his analysis of modernity, nevertheless develops powerful tools which help us to understand the general dynamics of globalization, and hence the heuristic concept of the Atlantic visualscape. “Disembedding mechanisms,” that is, mechanisms that have lifted out the local interaction context, Giddens says, have contributed to the development of the modern world. One of these mechanisms is symbolic tokens such as money.13 I argue that photographs, and in particular portrait photographs, can be looked at in the same way in which money is a means of time-space distantiation within the dynamics of globalization. This close relationship between money and photographs was indeed already observed by Oliver Wendell Holmes, a Boston medical doctor, in an essay he wrote in 1863. “Card portraits,” he said, “as everybody knows, have become the social currency, the ‘green-backs’ of civilization.”14 Photographs can be equated with money since both (within an enlarged economy in the sense of Bourdieu), like all disembedding mechanisms, depend on trust.15 Trust, Giddens says, is vested not in individuals but in abstract capacities.16 In the case of money, trust is embodied in the fact that others, whom one never meets, honor the value of monetary tokens. In the case of photographs it is vested in the expectation that what a photograph shows is a piece of the real world or a real person who has been “there” in the very moment when the photograph was taken. Or, as Lady Eastlake said in the late 1850s, “[photography’s] business is to give evidence of facts, as minutely and as impartially, as, to our shame, only an unreasoning machine can give.”17 The idea of trust that people bestow on the expert system photography is also very well illustrated in Kodak’s 1888 slogan, “You press the button, we do the rest.”

The processes of circulation, production, and consumption of photographs run by no means unilaterally. African elites who used photographs as a medium for representation and self-portrayal purposefully let their images circulate in the Atlantic visualscape.18 Also, Africans themselves began to work as photographers, and Europeans had their portraits taken in studios owned by Africans.

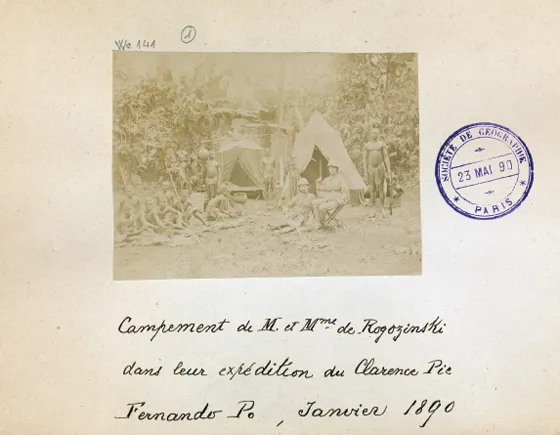

FIGURE 1.2. John Parkes Decker, Campement de M. et Mme. de Rogozinski dans leur expedition du Clarence Pic, Fernando Po, Janvier 1890. COURTESY OF SOCIÉTÉ DE GÉOGRAPHIE/BIBLIOTHÈQUE NATIONALE DE FRANCE.

The First African Photographers

Photography arrived in West and Central Africa shortly after its invention was officially made public by the French government in 1839.19 It seems that by the early 1880s it was widely known and practiced in the coastal areas and to a lesser extent in the hinterland.20 Those who had contributed to the spread of the new technology were white traders, explorers, and adventurers who either used a camera themselves or possessed photographic images that were accessible to Africans. Photographs were also frequently taken by French and British naval officers. This was confirmed by contemporary travelers such as the hunter Henry Astbury Leveson, Consul Richard F. Burton, and the Liverpudlian trader John Holt.21 Missionary societies, too, recognized photography’s potential very quickly.22 And Africans themselves appropriated the technology and began to work as photographers, seeking clients among the African and European population living in the coastal economic centers who were interested in having their likenesses taken and could pay for it in cash.

There are still many open questions as to who the first African photographers were, what their social backgrounds were, where they learned their profession, and what their formal and aesthetic models were. Recent research has shed light on the African American Augustus Washington, who moved in the 1850s to Liberia and later ran temporary studios in Sierra Leone, The Gambia, and Senegal.23 Several of his daguerreotypes, which at the time were destined for the American Colonization Society, have survived in various American archives. Erin Haney writes in this volume on the history of photography in West Africa, giving a comprehensive analysis of the Lutterrodts, a widely ramified dynasty of photographers rooted in Accra (Gold Coast, now Ghana). Lutterodt family members ran fixed studios in Gold Coast, Sierra Leone, Duala, and possibly Fernando Po, but they were also working itinerantly along the West African littoral. The first photographic activities of the Lutterodts, most likely of Gerhardt Lutterodt, date back to the early 1870s.24 Lisa Aronson and Martha Anderson are also currently working on a research project about J. A. Green, an African photographer who was active in the Niger Delta in the late nineteenth century.25 Some biographical details are also available for Fred Grant, a Cape Coast man whose first photographs date—as far as we know—from 1874.26

Surveying the period between 1840 and 1880 we observe that the first photographs that may be dated with certainty, apart from those by Augustus Washington, were made in the late 1860s or early 1870s. I cannot confirm Vera Viditz-Ward’s statement that “by the 1850s there wer...