![]()

1Women and Gender in Africa before 1700

THE EARLY CENTURIES of African civilization and community are the most difficult to study, and it is complicated and frustrating at times to find information about women in early African history. Yet recent advances in historical research, involving the expanded use of historical linguistics and new approaches in archaeology and art history, have brought greater insight into gender and women during a time when there was little to no European contact. While some documents exist, they are scarce, and the earliest written sources from European visitors tend to focus on unusual elite women, with the day-to-day activities of the vast majority of African women remaining obscured.

Nonetheless, the evidence points toward women’s central role in their societies and their leadership potential, especially in communities that followed matrilineal lines of succession. Sources also detail the impact of female decision-making regarding agriculture, family configuration, and religious beliefs. Women were involved in the economy from the earliest times, particularly through their work cultivating crops and participating in local and long-distance trade networks. They were also likely responsible for items essential to community well-being, such as making cooking pots and introducing food preparation methods. Despite the crucial nature of women’s contributions, notably as mothers to future generations, they were rarely recognized with a public form of authority. Though African settlements were more often led by men, women frequently played an essential advisory role, and at times they were recognized as chiefs.

The significant role of women in organizing their communities and ensuring the continuity of their families and societies is a critical point of departure for understanding African history. Women’s choices and activities shaped the ways in which African societies developed over the following centuries.

Women in Early African History

Research into early African history, referring to the centuries prior to 1500, has uncovered some information about African societies, though frequently such material is not specifically gendered.1 Using innovative methods such as historical linguistics and archaeology, scholars can discover specifics about early African communities. Historical linguistics is a research method that traces the development of language and the introduction of terminology to analyze the presence of certain material goods and particular social practices. Generally, however, while such studies demonstrate that early peoples in the Great Lakes Region of central Africa grew millet, yams, and bananas, they cannot prove that agriculture or food preparation was specifically women’s work or men’s work. A close investigation of language and ethnicity from the perspective of women’s roles in families and as religious leaders illuminates our understanding of social relationships more generally. For instance, describing the linguistic history of terms referring to mothers helps historians understand early family formations. Researchers combine insights from historical linguistics and archaeology to develop ideas about motherhood, early cultivation, and religious beliefs that present some sense of what women’s lives might have been like.

Archaeologists have studied housing, farming techniques, and tool and equipment manufacturing based in part on remnants of settlements and artifacts, but again, they cannot always state whether such tasks were the responsibility of men or women. Historical evidence reveals how people in the northeastern regions of the continent developed pottery as early as 9000 to 8000 BCE and how that technological innovation allowed them to use local grains such as sorghum and pearl millet to make porridge, a food that became a staple that was supplemented with vegetables and meat. The difficulty is that the evidence can show how bananas, for instance, became an important crop in the area now part of Uganda, but it cannot definitively demonstrate the gender division of labor.2 Nevertheless, it is quite plausible that women prepared and cultivated food, along with making pots and other tools needed for that work in the early eras of human activity.

The earliest millennia brought some key developments in human society, including the domestication of cattle, sheep, and goats in northern regions of the continent. Although many communities pursued a nomadic life, for others, caring for livestock on a regular basis required digging wells and building more permanent settlements. That in turn affected the housing style, which by 7000 BCE was typically a family compound of multiple structures surrounded by thorn-bush fencing. Along rivers, lakes, and seacoasts, other communities were becoming expert at fishing as the basis for their livelihoods. People were also making progress in the domestication of plants for consumption and other uses. Spindles for spinning cultivated cotton into thread dating back to 5000 BCE have been found.

In West Africa the earliest agricultural communities relied on tubers such as yams, which were grown by planting a section of the yam itself, rather than propagating seeds. They also nurtured tree crops, notably oil palm and raffia palm. The latter was used to make palm wine and as a fiber to make clothing and other household supplies. The main domesticated animal was the guinea fowl.

Southern Africa supported nomadic groups of hunters and gatherers, with settled agricultural communities developing slowly over millennia as northern cultivators expanded into forested areas and planted crops in savannas, gradually moving south across the continent. Africa remained the least densely populated region in the world. While there were a few areas of concentrated populations in towns and cities, most Africans lived in widely dispersed villages and small-scale settlements that supported localized, nonhierarchical political and social structures.

Using the study of historical linguistics, researchers have found that terms related to life cycle events have origins as early as 3000 to 1000 BCE. It appears that boys were circumcised as part of initiation rites, while girls were not. Girls participated in ceremonies marking the onset of puberty when they became “young women,” and following the birth of their first child, which brought them into the status of adult women. The absence of linguistic evidence for marriage as a key event in women’s lives suggested that marital bonds may have been weak. However, the ability to become pregnant, which was signaled by the beginning of menstruation, and pregnancy itself resulting in the birth of new members of the clan were significant since those changes in biological status marked the continuity and possible expansion of the community.3

Rock art paintings found in the Western Cape region of southern Africa frequently included human figures. The paintings are ancient, predating the earliest settled communities that appeared at the beginning of the Common Era. The artists in many cases were careful to distinguish men from women by showing exaggerated sexual characteristics (penises on men, breasts and large buttocks on women). The paintings show men with their hunting bows and quivers and a few women with the digging sticks they used to gather roots and other foods, though the most common images are of groups or lines of people, possibly involved in ritual dancing or other community activities.4

Hunting and Gathering

The earliest human societies were most likely based on gathering foods that grew in the wild and on hunting animals, with more settled agriculture and herding activities developing gradually over many centuries. There was no sharp division between settled agriculturalists and nomadic societies based on gathering. The boundary that divided hunting and gathering groups from nomadic pastoralists was also fluid, as both groups moved around on a seasonal basis to find food and water, and gatherers at times kept small numbers of cattle, goats, or sheep.

The conventional discussion of such groups described men as hunters and women as gatherers, a depiction that positioned men as more important in such societies, based on an assumption that the meat caught by male hunters was the primary food source. While it is likely that there was a gender division of labor, based in part on the need for women to bear children and care for them during the earliest months of breastfeeding, research does not support such a strict division between women’s and men’s work. Studies focused on women found that men also gathered and women sometimes hunted, particularly for smaller animals and birds. Women’s hunting activities included traveling to seek animals, as well as setting traps and attracting desired animals and birds so that they could be caught through more passive methods. In addition to understanding that hunting was not only a male activity, analysis has shown that daily meals and the bulk of the diet in the family and community relied on women’s foraging and food preparation of grains, nuts, fruits, eggs, and other foods, with meat supplying an occasional source of protein rather than daily sustenance.

Many societies changed over time, but such change was not necessarily perceived as a positive development or as steady progress to a more “civilized” social order. Hunting and gathering communities were particularly suited to their environments, especially as seen in their use of more simple technologies. Societies based on hunting and gathering that continue to exist have usually been found in some of the most difficult climates on earth, in areas where settled agriculture was difficult to sustain. In Africa, such regions included the desert areas of southern Africa, as well as the densely wooded rain forests of central Africa. At the same time, those societies were not static.

Twentieth-century examples of such societies may provide clues to the past but should not be considered exactly the same as societies from past millennia. A more variable division of labor was often related to less complex social and political structures. Hunters and gatherers typically had very small-scale, egalitarian and flexible formations, with few tasks being considered only men’s or only women’s responsibility. Where there was little stratification along political or economic lines, gender constructions were also less hierarchical.

These basic factors persisted among the Aka peoples of the forests of the Central African Republic in the early twenty-first century. Women were sometimes seen hunting with a knife or spear, with a baby in a sling at their sides. The Aka practiced net hunting, and that was often a task done by the whole family. Men joined their wives in collecting mushrooms, wild nuts, and forest tubers. One woman told how her husband and family would praise her for her bravery when she went alone to dig for yams in the forest, where she risked encountering dangerous wild animals. Fathers spent much of their time caring for their children, more than was found in any other human society that has been studied. The near absence of a gendered division of labor was reflected in an extremely nonhierarchical social order.5

In addition to comparisons with modern hunting and gathering groups such as the Aka or the San in southwestern Africa, studies of early hunting and gathering groups have drawn information from archaeology. Evidence found at sites where people lived in the distant past is highly scientific, relying on using isotopes to date particular findings and microscopically studying tools, human remains, animal bones, and food refuse such as seeds and shells. The interpretation of that evidence is often contested among archaeologists, and it rarely provides an exact portrait of how early peoples organized their societies and lived from day to day.

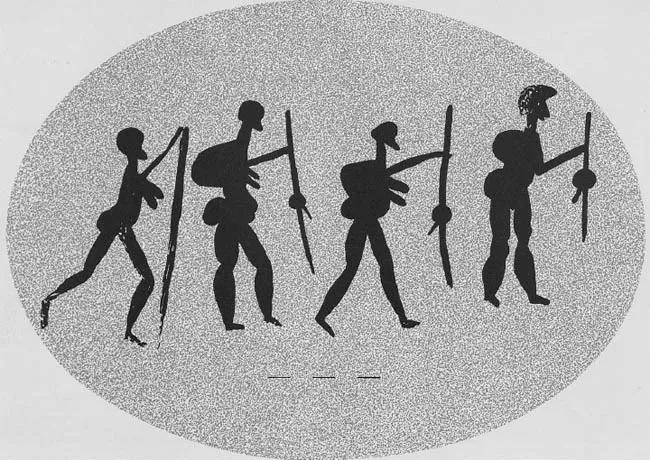

Fig. 1.1 South African rock painting showing women with bored stones weighting their digging sticks; the original art was painted directly onto rock face circa 1000 BCE. Source: Patricia Vinnicombe, People of the Eland: Rock Paintings of the Drakensberg Bushmen as a Reflection of Their Life and Thought (University of Natal Press, 1976), 276.

For instance, studies revealed that stones shaped into smooth ovals with a hole bored through the center were often made by women for use in their gathering activities. A digging stick could be fitted into the center hole of the stone, which would then give weight to the stick and facilitate women’s work of digging for roots, water sources, and other requirements for the desert-dwelling San. Bored stones found in the region have been dated as twenty thousand years old, though San women were still observed making and using such stones in the twentieth century. While bored stones may also have been used as weapons and as a hunting tool by men, they were certainly among the earliest known tools used by women in collecting food.6 They might also have been used in ceremonies in which women beat on the ground with the stone in order to communicate with spiritual leaders and ancestors.

Among the Namaqua, a Khoekhoe group in southern Africa, women performed most of the domestic labor, including collecting water and firewood, milking the stock, and preparing food. Women owned the huts and the cooking implements and pots. Many women also had their own cattle or goats that they inherited from their parents, and they controlled the distribution of milk products. Close family relationships meant that men had deep concern for their own sisters, which informed their attitude to other women in the group. While there was certainly competition over access to resources, and men were recognized as community leaders, women were not completely subordinate. They were respected as a result of their central contributions to the well-being of the community and were able to play an influential role in the day-to-day activities and long-term decisions of the group.7

Increased knowledge and understanding of how ancient hunters and gatherers functioned has indicated the central roles of women both materially and politically, as they contributed to the physical survival of their societies and participated in the daily decisions and seasonal rituals that insured the continuation of the group as a cohesive whole.

Early Women Rulers in Ethiopia

Some of the earliest information on individual African women comes from Ethiopia, which was the center of a long-standing Coptic Christian community. People followed a strong set of beliefs drawn from the Bible and their relationship with King David, his son King Solomon, and the Queen of Sheba, also known as Makeda. Makeda was acknowledged as the founding ruler of Ethiopia in the tenth century BCE. As the story was told in the Kebre Negest, an important source for Ethiopian history, she traveled to Jerusalem to learn from Solomon and returned to Ethiopia to have his child, Menelik I. She abdicated in Menelik’s favor when he was twenty-two years old, and that dynasty continued into the twentieth century. In Arabic legends she was known as Bilkis.

Some sources refer to another early ruler as “Candace,” suggesting that Candace was a proper name, but it was a title equivalent to queen (alternately, Kandake) in the ancient Kushite kingdom of Meroë, which flourished for 1,250 years until 350 CE. The title appeared to last for five hundred years (from the third century BCE until the second century CE). There were four women most often cited as Candace: Amanerinas, Amanishakhete, Nawidemak, and Maleqereabar, each of them powerful rulers in a kingdom known for strong female leaders. One converted to Christianity after she was influenced by a slave in her entourage who was baptized by St. Philip (Acts of the Apostles 8:28–39, KJV). Another, probably Amanerinas (and perhaps the same Candace as the convert)...