![]()

1 Influence of L1 Thinking for Speaking on Use of an L2: The Case of Path Expressions by English-Speaking Learners of Chinese

Shu-Ling Wu

The relationship between spatial language and cognition has been the subject of an active and growing line of research (e.g. Bowerman, 1996; Choi & Bowerman, 1991; Gathercole, 2009; Hickman & Robert, 2006; Narasimhan & Brown, 2009; Slobin, 1998; Slobin et al., 2010; Talmy, 1985, 2000; see also Guo et al., 2009). Space is fundamental to human cognition. Children learn to describe spatial relations and motion events at a very young age (Berman & Slobin, 1994; Bowerman, 1996). Although all languages provide ways to talk about spatial relationships and motion, features of the same spatial information can be mapped to different linguistic units and be selectively represented in foregrounded or backgrounded constituents across different languages. As illustrated by Langacker’s (1987, 1991) discussion of construal, a speaker can subjectively decide what aspects of a situation he or she selects to portray. For example, when describing the motion event of a plane taking off, individuals may choose to profile different points of the trajectory, as in the plane flew off the runway, where the speaker stresses the source of the motion; whereas in the plane flew into the sky, where the speaker highlights the goal. Moreover, previous studies provide converging evidence that speakers of different languages conceptualize spatial relationships and motion in a language-specific manner (e.g. Bowerman, 1996; McNeill & Duncan, 2000; Slobin, 1996b, 2004; Slobin et al., 2010; Talmy, 1985, 2000). For instance, the spatial category that the English placement verb put can describe is subdivided into two placement verbs, legen ‘lay’ and stellen ‘make stand’ in German (Slobin et al., 2010). The verb legen ‘lay’ is used when the object is placed horizontally, whereas stellen ‘make stand’ is used when the object is placed vertically. In addition to semantic variation in the category of placement verbs, cross-linguistic variation in path expressions is also identified. Choi and Bowerman (1991) observed that English and Korean children used and understood path expressions according to the categories of each language. For example, Korean-speaking children, like Korean adults, distinguished motion between tight-fit (kkita, for ‘putting a ring on a finger’ or ‘putting a book in a case’) and loose-fit events (nehta, for ‘putting an apple in a bowl’ or ‘putting a book in a bag’). By contrast, English children distinguished the spatial distinctions between in (putting objects into a container) and on (putting objects into contact with a flat surface), regardless of the differences between tight-fit and loose-fit. Such language-specific differences have been observed from as early as 16–20 months. For L2 researchers, the research question of interest is to what degree the predispositions for spatial organization or event construal established during first language (L1) development play a role during adult second language (L2) acquisition.

The study reported in this chapter is intended to contribute to the understanding of how L1 conceptualization of motion may exert influence on L2 use and acquisition of path expressions. It compares the behavior of 80 English-speaking L2 learners of Chinese to that of two baseline groups of 40 native speakers (NSs) of Chinese and 40 of English. The theoretical background and a review of the relevant theoretical and empirical research will be presented first. After that, the differences between Chinese and English in terms of path encodings and potential sources of challenges that are associated with learning L2 Chinese path expressions will be discussed. Next, the design and results of the study will be presented and explained. Based on the findings, the various contributing factors that influence the use of L2 Chinese path expressions by adult L1 English speakers will be discussed.

Background

Languages differ widely in the ways in which they describe the path information of a motion event. The path in this case is, by definition, the course or trajectory of the motion. Slobin (2004) specifies that path components comprise: (a) direction of the motion, such as into or up; (b) deixis or direction with regard to the viewpoint of the speaker; or (c) contour, such as zigzag or curved. According to Talmy’s (1991, 2000) binary typology of motion events, languages can be divided into either satellite-framed languages (S-languages) or verb-framed languages (V-languages), depending on how the path is encoded for events involving movement.

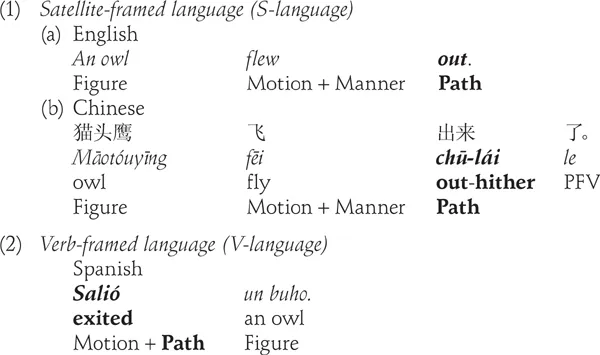

S-languages, such as English and Chinese, characteristically conflate motion and manner/cause in the main verb and encode the path of movement in a satellite attached to the main verb, whereas V-languages like Spanish and other Romance languages typically encode the path in the main verb. For instance, when describing the same motion scene of an owl flying out of a hole in a tree, speakers of typologically different languages depict the path in distinct manners. Consider the following motion sentences describing an owl’s movement:

As shown in Examples 1a and 1b, in S-languages, the path component is encoded in a satellite, namely, out in English and chū-lái in Chinese, while the manner and motion are conveyed via the main verb. The English path satellite out and the Chinese directional complement (DC) chu-lai ‘out-hither’ each relate to the main verb as ‘a dependent to a head’, according to Talmy (2000: 102), and thus are typical examples of path satellites. By contrast, Spanish, a V-language, conflates path together with motion in the main verb salió ‘exit’. Talmy’s distinction not only captures the systematic differences between languages of the two types in terms of how path information is encoded, but also provides implications for studies of L1 and L2 learning.

Extending on Talmy’s insights, Slobin (1996a, 1996b, 1998, 2004, 2009) and his colleagues have conducted cross-linguistic and developmental studies to explore the impact of motion event typology on language use. Analyses of the narrations produced by speakers of S-languages (English and German) and V-languages (Hebrew, Spanish and Turkish) showed that speakers of S-languages demonstrated a higher degree of elaboration in their descriptions of path of motion than did speakers of V-languages. Specifically, speakers of S-languages tended to specify details concerning the moving figures along the paths by attaching several path satellites to a single main verb. However, it would require separate path verbs in V-framed languages to express such complex path information. It was observed that speakers of V-languages tended to analyze the paths into fewer components, and they preferred to describe the static scenes in which the movement took place and to leave the details of the paths to be inferred. These distinctive typological preferences could be observed from as early as three years of age.

Slobin (1987, 1996a, 2003, 2009) has proposed a thinking-for-speaking (TFS) hypothesis – a particular kind of language–cognition interface phenomenon – to account for the cross-linguistic differences in the way speakers of different languages describe paths of the same motion events. TFS is ‘a special form of thought that is mobilized for communication’ (Slobin, 1996a: 76). He suggests that, when acquiring their L1, children of individual languages gradually become attuned to different aspects of motion events, so as to develop language-particular patterns of TFS. As illustrated in the owl examples, in order to succinctly describe the owl’s movement in the evanescent time frame in which utterances are constructed, speakers of S-languages attend to the manner of the motion as well as direction. Moreover, Chinese NSs focus not only on the directionality of the path, but also on the deictic relationship between the moving figure and the interlocutor/observers. In contrast, speakers of V-languages do not attend as much to either the manner or the deictic relationship inherent in such a motion event, and such event components tend not to be linguistically encoded in their languages. That is, the conceptualization of path information is filtered through language-specific semantic structures and through habits of TFS developed in L1 acquisition. Such TFS patterns vary considerably from language to language and can be observed in all forms of linguistic production and reception (i.e. thinking for...