eBook - ePub

Refugee Resettlement in the United States

Language, Policy, Pedagogy

Emily M. Feuerherm, Vaidehi Ramanathan, Emily M. Feuerherm, Vaidehi Ramanathan

This is a test

Buch teilen

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Refugee Resettlement in the United States

Language, Policy, Pedagogy

Emily M. Feuerherm, Vaidehi Ramanathan, Emily M. Feuerherm, Vaidehi Ramanathan

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

This edited volume brings together scholars from various disciplines to discuss how language is used by, for, and about refugees in the United States in order to deepen our understanding of what 'refugee' and 'resettlement' mean. The main themes of the chapters highlight:

- the intersections of language education and refugee resettlement from community-based adult programs to elementary school classrooms;

- the language (of) resettlement policies and politics in the United States at both the national level and at the local level focusing on the agencies and organizations that support refugees;

- the discursive constructions of refugee-hood that are promulgated through the media, resettlement agencies, and even the refugees themselves.

This volume is highly relevant to current political debates of immigration, human rights, and education, and will be of interest to researchers of applied linguistics, sociolinguistics, anthropology, and cultural studies.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Refugee Resettlement in the United States als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Refugee Resettlement in the United States von Emily M. Feuerherm, Vaidehi Ramanathan, Emily M. Feuerherm, Vaidehi Ramanathan im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Sozialwissenschaften & Aus- & Einwanderung. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Thema

SozialwissenschaftenThema

Aus- & Einwanderung1Introduction to Refugee Resettlement in the United States: Language, Policies, Pedagogies

Emily M. Feuerherm and Vaidehi Ramanathan

Situating Discourses of Refugee Resettlement

This volume brings together some leading female scholars writing about refugee resettlement, focusing on discourses of the lived, local experiences of refugees and asylum seekers as they are resettled in countries of asylum. Each chapter unravels the complex discursive constructions that position refugees as needy and burdens upon local and state resources, while questioning and analyzing the assumptions upon which such constructions are based. Such discursive practices have serious effects on several aspects of resettlement: upon refugees’ experiences of resettlement and their ability to adapt to the country of asylum; upon the policies which guide and provide resources for resettlement; and upon the ways in which educational resources are developed and administered. This collection is centered on how language is used by, for and about refugees by authors from various disciplines. Such an interdisciplinary investigation serves to broaden our understandings of what refugee and resettlement mean.

Research about refugees in applied linguistics has focused on several specific orientations: language use in the asylum-seeking process, positionings in the media and the educational experiences of refugees in or from particular geographical locations. For example, Blommaert (2009), Eades (2005, 2009) and Maryns (2005) each discuss how asylum seekers’ linguistic background is used in the asylum-seeking process, often resulting in limited access to refugee status. Gabrielatos and Baker (2008), KhosraviNik (2010) and Leudar et al. (2008) show the ways that refugees in the UK are positioned in relation to other groups of immigrants, finding regular themes of hostility, misidentification and other negative discourses. The educational needs and experiences of refugees are perhaps the most well researched (e.g. Cranitch, 2010; Delgado-Gaitan, 1994; Dooley & Thangaperumal, 2011; Elmeroth, 2003; Finn, 2010; Fridland & Dalle, 2002; Kanno & Varghese, 2010; Naidoo, 2011; Stevenson & Willot, 2007; Tollefson, 1989; Watkins et al., 2012; Windle & Miller, 2012). Such work is increasingly beneficial as the number of refugees worldwide climbs, and the populations seeking asylum continue to change. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees’ (UNHCR) 2014 report, 13.9 million people were newly displaced in 2014 due to conflict or persecution, 51% of whom were under 18 years old (UNHCR Global Trends, 2015). As of 2014, 59.5 million people worldwide have been displaced, a 40% increase within a span of just three years (UNHCR Global Trends, 2015: 5). Such violent displacement of people around the world affects our understanding of traditional concepts of home, identity and citizenship (Feuerherm, 2013). Critical scholarship is needed to understand the causes and effects of such global flows of asylum seekers. This volume highlights the unique human flows of displacement and the resources and expectations these immigrants have as they seek asylum and a new home. In this volume, particular attention is paid to the ways that policies and pedagogies constrain or make room for resettlements of different kinds.

The chapters in this volume contribute to established scholarship regarding the educational needs and best pedagogical practices for local communities of refugees (Due & Riggs, 2009; Finn, 2010; Kanno & Varghese, 2010; Watkins et al., 2012; Woods, 2009), and they also contribute to interdisciplinary understandings of what it means to be a refugee as seen through the policies affecting their resettlement (Blommaert, 2009; Eades, 2009; Ricento, 2013). The discourse used in the media regarding refugees and the language policies which affect resettlement mold communities’ perceptions of refugees (Gale, 2004; Leudar et al., 2008). Refugees themselves may react in different ways to the label refugee, either choosing to disassociate themselves from the term to avoid negative associations and connotations, or identifying themselves with the label in order to access legal rights or resources. Language is at the crux of these issues, and each of the chapters that follow highlight the linguistic issues as they relate to refugee resettlement policies, practices and pedagogies.

Why Focus on Refugees?

Refugees are a very specific group of political immigrants, and the policies around their resettlement are complex. They are distinct from other immigrants for a confluence of reasons: (1) they are not voluntary or economic immigrants.1 Refugees are forced to flee from their homes because of persecution and are resettled in countries and cities based on allowances and services, not personal choice. (2) Refugees have legal status which provides them with special services upon arrival, including funding and welfare access, as well as work permits and access to training and educational resources. (3) Refugees arrive into a country of resettlement having survived traumatic experiences, often with limited or interrupted education, and regularly suffering from severe mental and physical health issues as a result of their lives in their home countries and refugee camps.

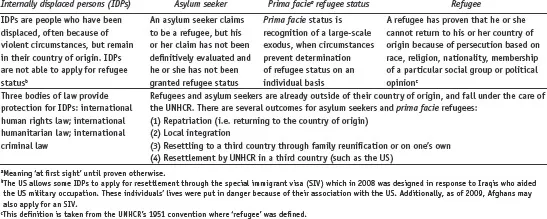

In order to better understand the refugee resettlement process, it is important to explore several of the keywords regarding refugees. Table 1.1 outlines some of the key policies regarding resettlement, especially who has access to refugee status.

The definitions in Table 1.1 are contested and the interpretation of these labels on the ground is often unclear (Gabrielatos & Baker, 2008). Those who must flee their homes in search of asylum are essentially political beings, involved in power – or its inverse, resistance – in its most basic and physical sense (Chilton & Schaeffner, 1997). The political pressures and the context of each case influence the ways that labels are applied. Williams (1976) presents the idea that keywords are those terms which are difficult to define because the semantic range is broad and tied to the socio-historical context of each utterance. Keywords, he argues, are especially those which involve ideas and values so that any investigation of the meaning of a word goes well beyond the ‘proper meaning’ to the range of meanings. Critically considering their internal developments, structures, range and edges uncovers the lack of neutrality with which they are used. The chapters in this volume will critically explore the keyword refugee, in relation to other keywords such as race, resettlement, self-sufficiency, support, immigrant, (dis)citizen, among others. However, throughout each chapter, it becomes evident that many of the crucial meanings have been shaped by those in power, while those who are labeled refugee, asylee or immigrant construct semantic webs that to varying degrees reproduce or counter recognized meanings. Such work illuminates the ideologies upon which these discourses are founded.

By critically analyzing the discourses which mediate access to refugee and asylee status, relationships of power and underlying ideologies are revealed. Ideologies both define groups (e.g. who counts as a legitimate refugee?) and place them in complex societal structures through their relationship to other groups (e.g. who is denied access to status or services?). However, ideologies are not solely social systems, but mental representations that have cognitive functions of belief organization of which individuals may be more or less aware (van Dijk, 1997; Fairclough, 2010). It is when these ideologies dominate and oppress social groups that researchers and practitioners must intervene on the side of the dominated in order to reveal oppressive regimes (Fairclough, 2010; Fairclough & Wodak, 1997). In other words, ideologies mitigate between language and social structures, and when social structures are oppressive, revealing the ideologies and discourses that legitimize such structures is necessary when attempting to resist them. The chapters in this volume uncover the dialectical relationship between the discourses, policies, ideologies and power/social structures that position refugees and their process of resettlement in very particular ways, as well as local discourses of resistance.

Table 1.1 Defining refugees, asylees and IDPs

Yet, there are gaps in research pertaining directly to the policies and pedagogies which affect refugees, particularly how ideological and discursive constructions shape their fates. Critically interpreting the policies of asylum seeking allows for a better understanding of the process of applying for refugee status in the US, particularly related to discriminatory practices and unequal treatment based on ideologies of asylum and refugee. Like Blommaert (2009), Eades (2005, 2009) and Maryns (2005), this introductory chapter presents issues of language in relation to the asylum-seeking process in order to orient the reader to some of the issues around becoming a refugee. However, rather than focusing on the language of the asylum claims and the beliefs about language that guide the claims’ analysis as previous research has done, this introduction will focus on the political constructions of asylum and refuge in policies. The goal is to show how forces of discrimination and unequal access are legitimized through the language of policies and demonstrate why a focus on refugees is important within the field of applied linguistics.

The following section explores the political nature of labeling, taking the current example of unaccompanied Central American minors crossing the Southern US border. This is an example that demonstrates the ways in which language, policy and ideology construct refugees, asylum seekers and resettlement. The following section is intended to provide the reader with some background and context for the larger issues which influence refugee resettlement, and the role of language in the construction of who counts as a refugee.

Unaccompanied Minors Coming to the US

The unaccompanied minors from Central America who have been crossing the Southern US border since 2013 are being labeled variously depending on the context and political orientations of the speaker. These unaccompanied minors are fleeing unstable and violent circumstances,2 and it seems as though they should be recognized as prima facie refugees (an estimated 57,000 arrived between October 2013 and July 2014), or at the very least asylum seekers. However, rather than being labeled as refugees or even asylum seekers, they are more commonly referred to in the media as children, minors or kids who are unaccompanied, undocumented, immigrant, migrant or illegal3 – the latter being the most problematic (see Wiley [2013] for a discussion of this). Such labeling erases the violence from which they fled and the potential for violence if they are repatriated, and focuses on their immediate status in the US through analogy to other immigrants.

United States immigration policy requires that asylum seekers must enter the country first, and then file the necessary documents to apply for asylum, regardless of age or ability. The application is only in English, spans at least nine pages and requires an interview where persecution and abuse are recounted in detail.

Furthermore, children – like adults – who have been apprehended are not provided with legal aid to navigate this process, unless they have the wherewithal to hire a lawyer or a pro bono legal service offers help. Congress directed the department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to ensure that the unaccompanied children would have counsel ‘to the greatest extent practicable’ but also they should ‘make every effort to utilize the services of pro bono counsel who agree to provide representation to such children without charge’ (American Immigration Council 2015). And yet, as of April 2015, over 38,000 children’s cases remained unrepresented, leaving these children to navigate the asylum process and the immigration court legal defense by themselves (American Immigration Council 2015). The Department of Homeland Security (DHS), on the other hand, has a lawyer trained in immigration law present at eve...