![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Arriving

After eight hours of hairpin bends, knife-edge ridges, spectacular views, dry riverbeds, dust and bumps we branched off the Trans-Flores highway. After a mile or so down a seemingly unpassable track my co-tour leader, Hilman, asked the driver of the local bus we had chartered to halt. Immediately we were surrounded, half-dressed children appeared, pushing their faces against the windows while others began climbing on the bus. Drums and gongs could be heard. Hilman and Pak Ben (a representative from the Department of Education and Culture) alighted through the back door, informing me simply ‘Sudah tiba‘ we had arrived.

The 13 tourists were clearly nervous as I translated our arrival and told them to follow me off the bus. Getting down from the bus past masses of children, I could see through the village entrance. Men were waving swords as they stamped the ground. With anxiety and trepidation I persuaded the tourists not to worry about their belongings on the roof and join me at the entrance. Behind the sword waving men, women, also in full ceremonial costume, danced.

The ‘welcome dance’ appeared more like a threatening war dance. The villagers didn’t seem to be smiling. The swords looked menacing and the repetitive rhythms on the drums and gongs compounded our sense of fear. Although I was leading my first tour, I knew that containing my own fear was necessary for the well being of my clients. My outward expression of excitement masked my inner turmoil of combined surprise and apprehension.

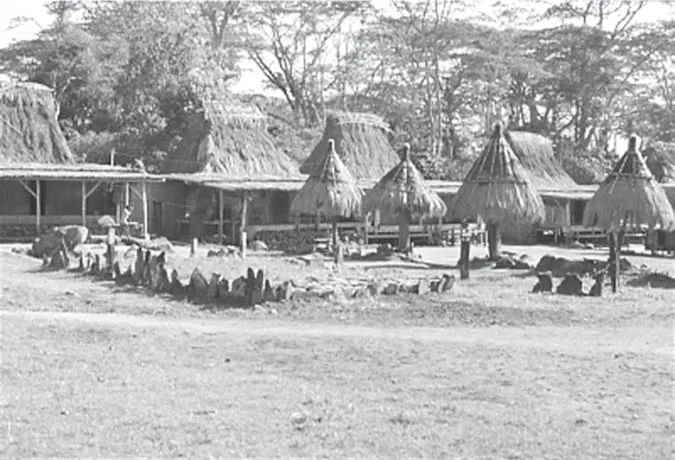

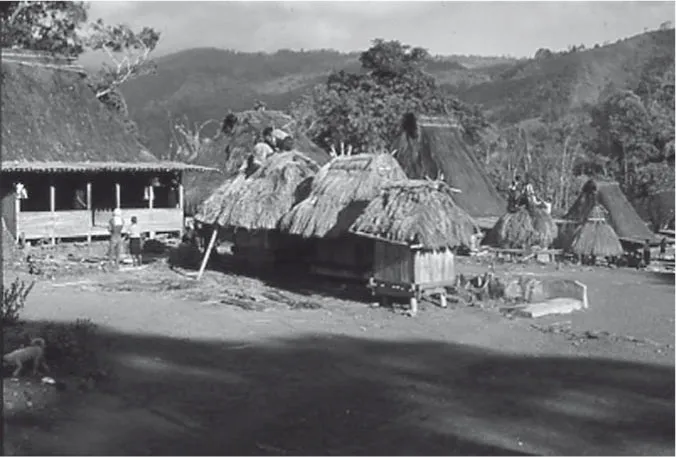

Following instructions from Pak Ben we followed the villagers around the village of Wogo passing in front of the 32 majestic wooden houses with high thatched roofs, to a house where we crowded on the terrace. In the centre of the village we could see stone structures or megaliths, clan posts (ngadhu) and miniature clan houses (bhaga) (see Plates 1 and 2). We were presented with drinks: very sweet coffee and sugared water (as tea). The children began by keeping a safe distance and staring. As they gradually inched forward, an adult would chastise them and they would retreat a few metres.

Plate 1 The lenggi and some ngadhu in Wogo

Plate 2 Re-thatching a bhaga in Bena

The 13 tourists were split between four houses to get to know their host families. Hilman and I shared our time between houses to help translate and settling. We ate our main meals in a fifth house but host families kept up a constant supply of snacks: roast sweet potatoes, boiled bananas and baked cassava.

The next 42 hours were partly negotiated on our reconnaissance trip1 but the villagers had put the main activities together. Briefly it involved: a cultural description of the village centre; a walk to observe local agriculture and palm toddy tapping; visiting villagers’ garden homes; walking to the local volcano to observe volcanic activity; bathing in a pool that had hot and cold water sources; a walk to the old village site and megaliths, where we had a picnic lunch of rice, pork and vegetables cooked in bamboo tubes over a fire, washed down with palm toddy; and a cultural show of songs and dances by adults and children.

As I had refused to allow individual tourists to tip individual villagers or households, the tourists had made a collection for the village. This raised a significant amount of cash which, following a discussion the villagers, was put towards a project to bring water to the village. After we had visited the village with three groups, the water project was up and running, and some of the villagers had had the opportunity to take part in a festival of international bamboo music in Bali. When we met again they asked me ‘How can we have tourism and not end up like Bali?’ The disturbing aspects of Bali that they described were the volumes of scantily clad tourists; the traffic jams; the wealth disparities, mansions and beggars; shops, hotels, and restaurants everywhere; and no peace at all.

On our fourth visit the villagers were faced with decisions of what to do with future finance raised from tourism. No consensus was reached during our visit. Unlike in any previous visit we felt unhappy about leaving money in the village. There were disagreements about who should look after it.

It was also on the fourth visit that our tourists encountered other tourists in ‘their’ village. In the afternoon a few independent tourists, arrived, looked around and departed. Later that evening, a guide arrived with a group of tourists just as our cultural show was about to start. I approached the guide and told him that we had sponsored the show and therefore found it unacceptable for his tourists to ‘watch for free’. The presence of other tourists detracted from my clients’ special event. The guide claimed to have permission from a villager, whom he had paid. I was powerless.

Visiting remote, untouched villages with anthropologists had become the unique selling point of our tours. When I heard my clients’ comments that the village was ‘obviously getting touristy’, I knew the competitive advantage of my company relied on finding a remoter village. However I have continued personal visits to Wogo for shorter (days) and longer (months) periods ever since.

On my visits we would always discuss tourism, its development and how things were changing, or not. As my visits continued and my role changed from tour operator to academic researcher it became clear that tourism was developing, but that the process was outside and beyond the villagers’ control. Their village was visited, and they became passive recipients of visitors without any signs of development. The village was not becoming ‘like Bali’, but the villagers were deriving no benefits from tourism, yet at the same time I felt sure that tourism was changing the village. Was the passivity confined to this village and if so why? From the early days of excitement and enthusiasm for tourism, why had their attitudes changed? With my changed role I ventured further afield to other villages in the Ngadha area to learn from them of their experiences and see for myself how they coped with tourism.

The Ngadha villagers have been incorporated into the cash economy requiring cash for taxes, schooling, health care and basic commodities. The opportunities for economic development in the area are minimal. Steep slopes and a harsh climate limit agricultural development. The area has no known mineral resources but does have thermal power. Industrial development is unlikely due to the region's peripheral position, far from markets and lacking entry ports either by sea or air. Cultural tourism development could potentially provide the villagers with opportunities to obtain cash. The villages have the raw cultural resources to provide the context for tourism although development requires their refinement for tourism consumption. Too little refinement and there is minimal economic benefit from tourism, too much and the resource is spoilt. Understanding the intricacies of the culture and the value systems of the actors is crucial to ensuring the sustainability of their tourism. This book details the first 20 years of tourism development, examines the values of key actors to identify real and potential conflicts, and discusses the ways tourism is incorporated into two of the villages: Wogo and Bena.

Themes: What This Book Is About

This book provides a holistic picture of the first 20 years of tourism development in two remote marginal villages. It provides the tourism story from multiple perspectives. It contrasts the values, attitudes and priorities of the different actors in tourism. It discusses how tradition, ethnicity and culture are strategically articulated, moulded, manipulated andused, to serve the different actors’ purposes. In doing so, the book reveals the ‘conflicts of tourism’ both between actors and because of tourism processes.

Based on 16 years of visits from 1989–2005 this book provides a rare longitudinal study revealing not only socio-cultural change and development but also changes in tourists’, villagers’ and the mediators’ attitudes and priorities. The book focuses on two villages and makes comparisons between them; this micro-level analysis shows the importance of very local detail and thus challenges some of the assumptions in the tourism development literature.

While this book is about tourism and socio-cultural change, it also highlights how globalisation can be about powerlessness and a lack of change. The ethnography provides a rich description of life in a non-western marginal community in a contemporary global context and how they face the challenge of balancing socio-economic integration and cultural distinction. It tells the story of how tourism has entered social processes in the villages, has brought dreams and hopes, and has affected the balance of power but has done little to change the economic situation of the villagers.

This book is not an exhaustive ethnographic study. It is a partial ethno-graphic study that deliberately focuses on some areas of the respondents’ lives. While the narrative concentrates on tourism and the changes it has brought about, it should be remembered that it is not possible to disaggre-gate socio-cultural change brought about as a result of tourism from other influences. Using a series of stories, vignettes and quotations from all the stakeholders I will attempt to evoke what life is like for the villagers in Ngadha. Their experience is only one part of the complex story; by examining the views of the other actors I hope to present a holistic picture, to reveal the connections and contrasts, and how these change.

Location

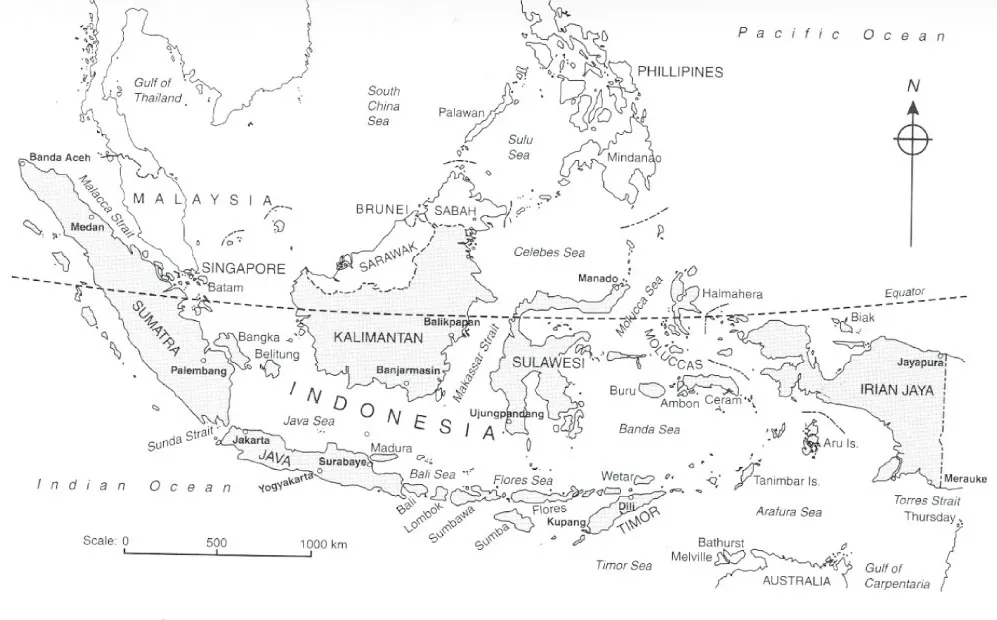

The Ngadha live in the rugged mountainous region between two active volcanoes: Inerie and Ebolobo2 in the south-east quarter of the Ngada regency. The regency (Kabupaten Ngada) is located in central Flores in Eastern Indonesia (see Figures 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3). Formerly part of the Dutch East Indies, the regency is known after its colonial name, Ngada, which is a misrepresentation of local pronunciation of the name. (The Dutch appear to have difficulty rendering the local ‘dh’ sound and wrote it as ‘d’.) The people in this study, however, call themselves – and are referred to by neighbouring groups when speaking Indonesian – as orang Ngadha. Outsiders continue to be confused by this, since the regency, a geographical designation, is spelt one way, Ngada, but a group of people living in the south-east corner use Ngadha.

Figure 1.1 Map of Indonesia

Figure 1.2 Map of the Eastern Isles

Figure 1.3 Map of Flores showing the location of the study

The Ngada regency lies between 8 and 9 degrees south and 120 and 121 degrees east (Kabupaten Ngada, 1998). As with so many areas of Flores, the area is subject to frequent seismic activity. The young volcanic soils are littered with volcanic boulders. Gradients vary across the region but over 40% of the land is very steep (Kabupaten Ngada, 1998). The area receives 1750mm of rain in the rainy season (October to April) and 157mm in the dry season, far more than the rest of the Kabupaten (Kabupaten Ngada, 1998). Temperatures range from between 20°C and 33°C in the day but can get down to less than 10°C at night in the mountains. However, significant variation exists between villages in terms of temperature and rainfall due to altitude and aspect.

The population of the regency in 1997 was recorded at 212,271, giving a population density of 70/ sq. km. However the Ngadha part of the regency is by far the most populated, supporting an average of 184/sq. km (ibid). The area is economically poor with one of the lowest per capita incomes in Indonesia (Rp900,000/yr approximately US$180) (Kabupaten Ngada, 1998). Communications in Ngada are also among the poorest on Flores. The area has one major tarmacked road, the Trans-Flores Highway, which runs east–west across Flores. Small single-tracked, partially tarred roads run off this main artery. A small airport north of the capital exists but has not been in regular use.

The Ngadha language is currently classified as belonging to the Centra...