eBook - ePub

Engineering Nature

Art and Consciousness in the Post-Biological Era

Roy Ascott, Roy Ascott

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 328 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Engineering Nature

Art and Consciousness in the Post-Biological Era

Roy Ascott, Roy Ascott

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

This is the third book in a series drawing on papers presented at annual Consciousness Reframed conferences. In addition to focusing on the 2003 conference, it also includes papers published in the journal Technoetic Arts. With some 45 contributors, each chapter presents current issues arising in the context of art, technology and consciousness.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Engineering Nature als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Engineering Nature von Roy Ascott, Roy Ascott im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Physical Sciences & Mathematical & Computational Physics. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

1. The Mind

1.1 Towards a Conscious Art

Robert Pepperell

The goal of a scientific study of human consciousness seems to be perpetually thwarted by a logical dilemma. Whereas conventional science proceeds through empirical observation of an extrinsic object by a scientific subject (for example, the mineral deposit is observed by the geologist), in the case of self–consciousness it is less clear how one person could objectively observe someone else’s inner experience. Despite the range of methodological tools available to experimenters, including introspective reports and sophisticated scanners, they are inevitably left with a rather second–hand picture of what is going on within the minds of their subjects, which are also their objects of study. Because the subject and the object become thus entangled in attempts to observe inner experience, it seems we might never be able to represent the self–conscious mind with anything other than itself. Without a way of representing, or even visualising subjective experience it could remain immune to scientific scrutiny.

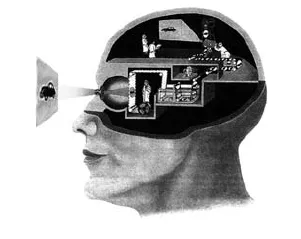

In an attempt to address this I propose that the concept of infinite regression, which is normally associated with the ‘homuncular fallacy’, be reinterpreted productively, in a way that puts self–reference at the heart of our conception of phenomenal experience. Infinite regression is a recurring motif in consciousness studies and is usually treated with suspicion at best and derision at worst. If the various sensory data we draw from the world is bound together somewhere in the brain and observed by an internal ‘self’ or ‘pilot’ to whom we can attribute the experience of existence, we run the danger of supposing a further pilot in order to account for the first pilot’s experience and so on. The problem is clearly illustrated in the following image, which suggests by its own analogy that to see the car on the miniature screen inside the subject’s head the clipboard–holding observers (suitably attired in white coats) should carry identical apparatus in their own heads of which they themselves are part.

The potential absurdity of this line of explanation has lead many thinkers to see infinite regression as sterile and to propose ways of describing consciousness that avoid invoking it (for example, Dennett 1991). But the fact that we bump up against infinite regression so frequently when trying to understand the self–conscious mind may suggest there is more at stake than a simple logical error.

Figure 1

I would suggest that there are in fact two kinds of infinite regression, which can broadly be categorised as conceptual and physical. Conceptual regressions, such as Aristotle’s ‘Unmoved Mover’ or the homuncular fallacy referred to above, are logically irresolvable. Physical regressions on the other hand, such as mirrors that reflect each other or cameras that see what they are recording, do not suffer the same logical flaw since the constraints of natural law demand that any self–referential physical system must reach some sort of resolution. So in the case of the self–reflecting mirror the very nature of light and the way it reacts to certain surfaces sustains a condition of infinite regression without leading to a conceptual black hole. One could say much the same about video feedback, which occurs when a video camera is suitably directed at a monitor displaying the camera’s output (the classic paper on the subject is (Crutchfield 1984). Here a number of non–linear attributes, such as screen discretisation, changing light levels and minute voltage variations, can produce an overall state of great complexity, beauty and variety from what is essentially an infinitely regressive process (see Web link in bibliography for examples).

The idea that consciousness may be linked to self–reference –that is, something looking at itself looking at itself ad infinitum –has a very long history, particularly in Eastern philosophy. In his book Zen Training, Katsuki Sekida (1985) outlines a theory of immediate consciousness using the behaviour of mental actions called ‘nen’, approximately translated from Japanese as ‘thought impulses’. For the purposes of this paper I want simply to sketch the basic principle of nen–action, introduced by a passage from the book itself:

Man thinks unconsciously. Man thinks and acts without noticing. When he thinks. ‘It is fine today,’ he is aware of the weather but not of his own thought. It is the reflecting action of consciousness that comes immediately after the thought that makes him aware of his own thinking ... By this reflecting action of consciousness, man comes to know what is going on in his mind, and that he has a mind; and he recognises his own being.

According to Sekida, thought impulses rise up all the time in our subconscious mind, swarming about behind the scenes, jostling for their moment of attention on the ‘stage’. Of these ‘first nen’, as Sekida calls them, most go unnoticed and sink back into the obscurity of the subconscious, perhaps to return later in some harmful form. But those that are noticed, just momentarily, by the reflecting action of consciousness (the ‘second nen’) form part of a reflexive sequence that supports our sense of self–awareness. The second nen follows the first so quickly they seem to occur simultaneously –they seem to be one thought. The obvious problem of how we know anything of this second nen is resolved by the action of a third nen which ‘illuminates and reflects upon the immediately preceding nen’ but ‘also does not know anything about itself. What will become aware of it is another reflecting action of consciousness that immediately follows in turn’ and so on. Meanwhile, new first nen are constantly appearing and demanding the attention of the second nen.

For the sake of simplicity this sequence is initially presented as a linear progression but Sekida goes on to elaborate the schema with a more subtle, matrix–like organisation while the basic principle remains. What follows from this is that, as Sekida states, ‘Man thinks unconsciously’; there is no localisation of conscious thought, no conscious object as such, other than an ongoing, infinitely regressive loop of self–reflections. Nevertheless, because of the rapid sequencing of the internal reflections, one has the impression of a sensible self, much in the way that one has the impression of moving objects in the cinematic apparatus. This theory would suggest that the notion of the ‘self’ does not exist outside a process of continuous self–reflection, nor in any part of that process.

Analogies between video feedback and consciousness

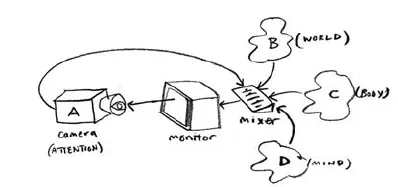

It was Sigmund Freud who, as far back as 1900 in The Interpretation of Dreams, suggested consciousness acted as a ‘sense organ for the perception of psychical qualities’ (Freud 1976) –in other words, as a ‘sixth’ sense. It does seem that self–consciousness allows us to see what we see, hear what we hear, taste what we taste, etc. Bearing this in mind (and referring back to the larger project of constructing a ‘conscious art’ system), I’d like to propose the following analogy between a video feedback system and a conscious being. Imagine an extended video feedback system that includes a video mixer that merges four distinct sources. The monitor not only displays the image from a camera –A –but also a ‘mix’ of three other sources, or sub–signals –B, C and D –such that all four sources merge in the monitor display and are observed by the camera. In such a set–up the feedback image generated by the looped signal A also incorporates the information from the sub–signals B, C and D. Whichever is the strongest sub–signal tends to have a greater influence on the overall properties of the feedback image. From this quite simple set–up one can draw surprisingly rich analogies with the operation of human consciousness.

Figure 2: Sensory self–awareness

As many have observed, consciousness is always consciousness of something and the content of our awareness is derived from one of three sources: objects in the world apprehended by the sense organs, sensations from inside the body (e.g. pains, tingles, hunger), mental data (e.g. ideas, memories, thoughts) or combinations thereof. Activity in the world, body and brain can go on quite happily without us being in any way conscious of it but something special or ‘phenomenal’ occurs when we do become aware of it. For the purposes of this analogy, think of the video camera as the agent of self–reflection that not only sees the combined data–sources of world B, body C and unconscious mind D (the ‘content’ selected for prominence by signal strength, or level of excitation) but sees ‘itself ’ seeing them, insofar as its own signal A is fed back into what it ‘sees’ (by analogy Freud’s ‘sixth sense’). As the signals flow an overall unitary state is reached that obviates the necessity for any further unifying agent, or homunculi, as the system is self–generating whilst also being infinitely regressive, or self–referential. The same principle might be applied to any reflexive sense: the smelling of smells, for example, or the feeling of feelings. Multiplied over the whole sensory system, one might start to speculate how a system with a capacity for self–awareness of some kind might emerge through having an integrated array of feedbacking self–sensors.

Perceiving continuity and discontinuity

Elsewhere I have argued that nature is neither inherently unified nor fragmented but that the human sensory apparatus gives rise to perceptions that make the world seem either unified or fragmented to differing degrees depending on what is sensed (Pepperell 2003). The process of infinite regression in video feedback illustrates how a complex, non–linear self–referential system can spontaneously give rise to patterns of similarity and difference. If consciousness is in any way analogous to video feedback it may help us to understand why, in a world that may be neither inherently continuous nor discrete, we are able to experience both qualities.

The binding problem

Some of the functional parts in the video feedback system are necessarily non–local (the camera lens must be a certain distance from the monitor) but are also connected by light or, like the brain, electrical conduits. In the case of video feedback, non–local components can give rise to coherent global behaviour that cannot be isolated to any part of the system. However, the feedback effect itself can only be observed locally; that is, on the monitor or in the camera eyepiece, despite the distributed nature of the system. Whatever the confusion or variation might be between the sources or sub–signals B, C and D in the analogy described above, the overall feedback image will retain a certain stability and unitary coherence as long as all the variables stay within certain parameters. This could be likened to the unitary coherence of first–person experience –the so–called ‘binding problem’.

The value of these analogies for the scientific study of consciousness is the way in which video feedback can practically represent the complexity that can emerge from a physical process that is essentially regressive. It may serve, therefore, as a means of analogically visualising what consciousness might ‘look’ like and thereby offering a way of observing the phenomenon.

Conscious art

I would like to sketch out, in very general terms, how these ideas might inform a practical investigation into the production of a self–conscious work of art.

It might be interesting for the reader to know that the ideas presented here originated less from the relevant philosophical literature than from a combination of introspection, personal experience and artistic enquiry. In particular, the practice of meditation and examination of its related philosophies have helped to clarify a number of issues to do with the behaviour of the mind and its relation to the body and the world. In addition, whilst using LSD some years ago I experienced vivid recursive patterns of luminous colour very similar to those seen in video feedback, which triggered an intuition about the self–referential operation of the visual system and by extension the mind. It is these experiences, together with the various pieces of interactive art I have produced and exhibited over the years, that have circuitously led me consider how it might be possible to construct an object of art that displays some self–awareness.

Using some of the principles discussed above, a system is envisaged that combines three sources of data from 1) the external world (with sensors for light, sound, and pressure, etc.), 2) the internal state of the system (such as levels of energy and rates of information flow, etc.) and 3) repositories of images, sounds and texts to be activated by rules of association (what one might describe, crudely, as ‘memories’). These three data sources will be synthesised into an overall system state, which is then ‘observed’ by separate sub–system of sensors, much like the video feedback referred to above. This observed state is then fed back into the overall system state and re–observed, indefinitely. In this way the system will generate a condition of infinite regress not dissimilar to that found in video feedback, which it is envisaged will achieve some overall coherence. At the same time, because conditions will constantly vary in the exhibition space (in terms of audience actions, internal system data states and associative links with stored data), the global behaviour of the system will be non–linear and unpredictable.

However, I should stress that I am not claiming any such system, even if it performed well, would actually be conscious in the same way that we are. Nor am I even claiming it would be quasi–conscious, or yet further, that it would be an accurate model of how conscious processes occur in humans. To claim any of these would not only pre–empt the results of the investigation but would suggest a far grander purpose than the thesis I have presented here could justify. At best the system might have a rudimentary functional self–awareness.

But even given the obvious limitations, I do expect many more artists to become interested in the creative possibilities of self–aware systems. This is on the basis that such systems will have unique and compelling qualities, including a capacity for producing semantic richness in response to audience behaviour, at the same time as generating a frisson of expectation amongst audiences as they apprehend an artwork that displays, albeit in the mildest of forms, some of the same sentient behaviour they recognise in themselves.

Conclusion

Infinite regression then, understood in relation to phenomenal experience, may be understood as a process of perpetual self–reference of self–observation, however this might occur within the physical substrate of the human system, the non–linear nature of which can give rise to intricate and novel behaviour. By exploiting the mechanical and analogical properties of video feedback systems, including their inherent complexity and creativity, one can envisage a functional model of a self–referential system that might inform a wider theory of a conscious, or self–aware art.

(This paper is based on a larger text published in Technoetic Arts Volume 1:2 2003).

Bibliography

Crutchfield, J. (1984). ‘Space–Time Dynamics in Video Feedback’. Physica, 10D, pp. 229–45.

Dennett, D. (1991). Consciousness Explained. London: Penguin.

Freud, S. (1976). The Interpretation of Dreams. London: Pelican.

Pepperell, R. (2003). The Posthuman Condition: Consciousness Beyond the Brain. Bristol:

Intellect Books.

Sekida, K. (1985). Zen Training: Methods and Philosophy. New York: Weatherhill.

www.videofeedback.dk/World/

1.2 Effing the Ineffable: An Engineering Approach to Consciousness

Steve Grand

The easy problem of ‘as’

According to the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, the word ‘ineffable’ has a number of meanings, one of which seems, inexplicably, to have something to do with trousers. More usually, it’s used to describe a name that must not be uttered, as in the true name of God, but it can also mean something that is incapable of being described in words. Consciousness, in the sense of what it really means to be a subjective ‘me’, rather than an objective ‘it’, might turn out to be just such a phenomenon. Language, and indeed mathematics, may be fundamentally insufficient or inappropriate as explanatory tools for describing consciousness, and Chalmers’ ‘Hard Problem’ (Chalmers 1995) might in the end prove quite ineffable.

Nevertheless, there are other means to achieve understanding besides abstract symbolic description. After all, even apparently trivial concepts are often inaccessible to verbal explanation. I am completely unable to define the simple word ‘as’ and yet I can use it accurately in novel contexts and interpret its use by others, thereby demonstrating my understanding operationally.

Linguistically speaking, an operational und...