![]()

PART I. POLITICAL PRINCIPLES, THE RULE OF LAW AND FOREIGN POLICY

![]()

1. POLITICAL PRINCIPLES

Provisions of the Association Agreement

The Association Agreement is premised on a commitment to pursue and respect:

…the common values on which the European Union is built – namely democracy, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms and the rule of law – [which] are essential elements of this Agreement.

The phrase “essential elements” links to Art. 478 of the Agreement, which provides that in the case of abuse of these principles the Agreement may be suspended.

Art. 6 provides for “dialogue and cooperation on domestic reform”. This political dialogue is conducted through regular meetings at different levels, including at summit, ministerial and senior official levels.

On the substantive implementation of the basic principles, the jointly agreed Association Agenda of 16 March 2015 is more explicit.3 Priority matters for short-term action include constitutional reform, election reform, judicial reform, human rights and public administration reform. These challenges are addressed in considerable detail.

Constitutional reform. The Ukrainian government is urged to embark on a transparent process of constitutional reform that aims to develop effective checks and balances between state institutions. The functioning of local and regional governments should be strengthened, including through decentralisation, in line with the European Charter on Local Self-Government and with the delegation of substantial competences and related financial allocations.

Electoral reform. Electoral legislation should be improved and harmonised, including the laws on referenda, on the Central Electoral Commission and the financing of political parties.

Human rights and fundamental freedoms. Ukraine has committed itself to a swift implementation of the judgments of the European Court of Human Rights. Awareness-raising among the judiciary, prosecution and law enforcement bodies is given special attention. The Association Agenda outlines measures regarding freedom of expression, assembly and association. On freedom of expression, best practices should be developed in public broadcasting and media access for electoral competitors, and freedom for journalists to work without the threat of violence, protected by law enforcement agencies. There is a need for legislation in line with best European practice on the freedom of assembly, and also to strengthen the awareness of law enforcement agencies. Regarding the freedom of association, the Agenda pays particular attention to ensuring the rights of minorities; the equal treatment of men and women; children’s rights; and combating torture and inhuman treatment.

The texts of the Agreement and Agenda are silent on the future political status of the occupied eastern Donbas region, although the Minsk II agreement raises the issues of decentralisation and elections.

The issues of judicial reform and corruption are taken up in chapter 2.

Implementation perspectives

The Constitution. According to its Constitution, Ukraine is a democratic state that adheres to the principles of the rule of law, human rights and fundamental freedoms. Ensuring respect for these principles, however, has proved to be problematic. Ukraine has been an unstable democracy so far. After gaining independence in 1991, the country experienced two periods of disguised authoritarianism (1995-2004 and 2010-14), which were ended only by massive public protest. After the last wave of protests, known as Euromaidan, Ukraine embarked on a path of democratic development, but the reform process has been slow.

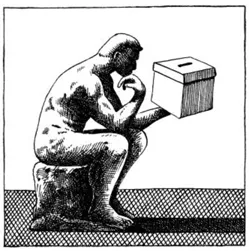

An overview of democratic governance. The most resilient component of the democratic system in Ukraine has been the ballot box. Although many of the elections in the 1990s and 2000s were not considered to be completely free and fair, they were still able to ensure a sizeable representation of the political opposition in the Parliament. They even produced electoral victories for the opposition in 1994, 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2010. After the Euromaidan the election process improved substantially. Despite a number of problems, most observers considered the elections in 2014 and 2015 to be generally compliant with international standards. Problems remain with the non-transparent financing of election campaigns, which allows wealthy businessmen and corrupt politicians to improperly influence the results with vote-buying and the abuse of power by officials.

Other components of the democratic system are weaker, however. After gaining independence, there was a power struggle between representatives of the executive and legislative branches of Ukraine’s government. The Constitution of 1996 established Ukraine as a semi-presidential republic, with a strong role for the president. But in the Constitution of 2004, adopted after the pro-democratic protests known as the Orange Revolution, the balance of power shifted towards a parliamentary system. Yet the new political system was flawed. A fierce struggle for power between President Viktor Yushchenko and Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko in 2007-09 reversed the gains of the Orange Revolution, and caused the country’s democracy to backslide in the subsequent years. In 2014, the Constitution of 2004 was reinstated, but once again power imbalances posed risks to democracy.

For most of Ukraine’s independence period, the principle of the separation of powers has not been implemented properly. The judiciary and the prosecutor’s office were prone to political influence by the executive and the legislative branches of government. The failure of the system was epitomised by the ‘general supervision’ function of the prosecutor’s office, which was allowed to check any individual or entity for compliance with the country’s laws. This function was the backbone of corrupt regimes. Recent amendments to the Constitution and plans to overhaul the justice sector are hopeful signs that improving the rule of law and fighting corruption are finally being taken seriously (see chapter 2).

Ukraine’s system of government is highly centralised, but with three levels of administrative, territorial entities: oblasts, rayons and towns/villages, each of which has elected representative bodies (councils). In reality the powers of these bodies are minuscule. Oblasts and rayons are governed by executives that are directly appointed by central government. As noted above, this system is currently under review.

Finally, the participation of Ukrainian citizens in politics and civic life is not effective. Although the share of Ukrainians who work in political parties or action groups is higher than in most EU countries, activists have little influence over their parties’ decisions. Ukrainian parties typically lack coherent ideologies and are just vehicles for their leaders and financial patrons. Most parties have a short lifespan (four out of the six parties that won the 2014 elections have been around for less than five years), and politicians often change party affiliation. As a result, political parties do not adequately represent large strata of society. Public trust in political parties, which grew in the 1990s and the first half of the 2000s, has fallen to 19% in recent years and has not really improved since the Euromaidan (24%).4 The share of Ukrainians working in civil society organisations was lower than in EU countries,5 although since the Euromaidan volunteer activities have accelerated.6

Reform of democratic governance. The scope of reforms since Euromaidan has been limited, and their pace slow. The reforms focused primarily on the decentralisation and independence of the judiciary, and less on contentious issues such as electoral rules. The problem of power distribution was not even mentioned in key strategic documents such as the parliamentary coalition agreement or the government action plan.

In March 2015, President Poroshenko established a Constitutional Commission with a mandate to draft amendments to the Constitution. The Commission, which was composed of legal experts and politicians, decided not to prepare a comprehensive bill to amend the Constitution at once. Instead, it began to draft separate bills aimed at resolving particular issues. In 2015, the Commission prepared three bills. The first one dealt with decentralisation, the second concerned the judiciary and the third revised the chapter of the Constitution on human rights. Another bill – on the procedure to remove parliamentary immunity – had been prepared prior to the creation of the Constitutional Commission, but it ran into problems with the Venice Commission of the Council of Europe.

The bill creating a framework for the decentralisation of power was completed by the Constitutional Commission in June 2015. It made provision for the establishment of local governments (executive committees) subordinated to the councils at the rayon and oblast levels. The local governments were intended to replace centrally directed local state administrations, which had to be dissolved. The bill provided few details on the powers with which the local governments had to be entrusted. Those details would have to be determined by later laws. The bill also established a framework for the modification of the administrative division of Ukraine, namely for the consolidation of the lowest-level administrative units. It was expected that 1,500-2,000 communities would be created instead of about 11,000 villages, towns, and cities (while higher-level units, rayons and oblasts, would be preserved). The decentralisation was planned for after the local elections, scheduled for October 2017.

The proposed amendments regarding decentralisation sparked two serious controversies, however. First, the bill determined that local self-government in the occupied areas of Donetsk and Lugansk regions might have special features, which was a requirement of the Minsk II agreement aimed at settling the conflict in the Donbas. A number of MPs and political activists vigorously opposed that provision, fearing that it might undermine Ukraine’s sovereignty. They believed that Donbas insurgents were effectively controlled by Russia, and that granting privileges to them would provide Moscow with a long-term lever to destabilise Ukraine and influence its policies. Second, the bill expanded the powers of the president, who would have the right to terminate the powers of locally elected officials and bodies if their decisions posed a threat to the national security or territorial integrity of Ukraine. Certain MPs deemed that this posed a risk of usurpation by the president.

With respect to the reform of electoral legislation, the authorities have so far fallen short of implementing the plans called for in the 2014 coalition agreement. The latter provided for a replacement of mixed proportional-majoritarian electoral systems with open-list proportional systems, for both parliamentary and local elections. The majoritarian component (single member constituencies) was widely seen as a key weakness of the electoral system, because that component created favourable opportunities for vote-buying and abuse of power by local officials. However, in July 2015, the Parliament introduced a proportional system for local elections that was not an open-list system. The new system preserved a strong degree of party control over candidates and did not resolve campaign financing issues. The question of parliamentary election rules was postponed. Nevertheless, the Parliament took a step to arrange party financing by passing laws that allow for public (budget) financing of parties that win elections.

Human rights. The Constitution of Ukraine proclaims that the main duty of the state is to affirm and ensure human rights and fundamental freedoms. The list of respected civil and political rights mentioned in the Constitution is consistent with international human rights norms. In practice, the majority of those rights and freedoms are generally protected. Notable exceptions concern the right to a fair trial, the right to an effective remedy before a national authority and the prohibition of torture. In the periods of backsliding on democracy, political rights were also significantly curtailed.

The Constitutional Commission has drafted a bill that revised the chapter of the Constitution on human rights. It is intended to align the contents of the chapter with the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, and to extend the protection of human rights. Specifically, it reduces the term for judicial approval for taking a person into custody from 72 hours to 48 hours. The bill explicitly prohibits the death penalty. The law on local elections that was passed in July 2015 determined that at least 30% of candidates on party lists should be women.

As a member of the Council of Europe alongside all EU member states, Ukraine adheres to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and Fundamental Freedoms and is bound by the rulings of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR).

Open issues regarding Ukraine’s record are set out in detail in the Association Agenda...