At the beginning of every organization, of every business, of every invention—of every life—is an idea. An idea that is good, or an idea that is bad, an idea that is yet to be proven, but still, an idea.

Look at your own life. Who you are is no magical accident—if you look closely, you will see that your life represents ideas others have had that influenced you, for better or worse, ideas you have had that have influenced who you became, and even ideas you never even knew had influenced you. Like the idea of relativity. The idea of gravity. The idea of human equality. The idea of time. The idea of space. The idea of God. The idea of justice. The idea of management.

Certainly each and every one of these ideas has influenced your life to some degree, yet how many of these concepts have you questioned? Perhaps in the early years of your life you did. But as we know, the older we get, the less we have time for serious questions. As we get older, the most serious of questions become unserious answers; we’ve got a job to do, and we do it. Yet it is these very serious questions, these very ideas, that shape the work that men and women do. That shape each and every one of us as managers.

History teaches us that an unchallenged idea can be a dangerous proposition. Still, every day, tens of thousands, even hundreds of thousands, of managers just like you go to work in an organization founded upon someone’s idea and assume the responsibility of making something happen. Whether or not the idea is still viable, still achievable, still sane.

It doesn’t matter what kind of company or which kind of department or division you manage—the fact that you’re trying to manage it at all is, based upon my experience, insane. Management, as we have come to know it, is the product of many years of insanity based on an idea that to manage means to strive to control everything around us. Something humans were never born to do.

It is my belief that our idea of management dates back as far as people do, thousands upon thousands of years, as do our ideas of power, of work, and of prestige; our ideas of systems and bosses and careers; our ideas of what it means to have a job and what it means to lose one.

And at the top of the list is the idea of what it means to be a Manager.

The Accidental Birth of Management

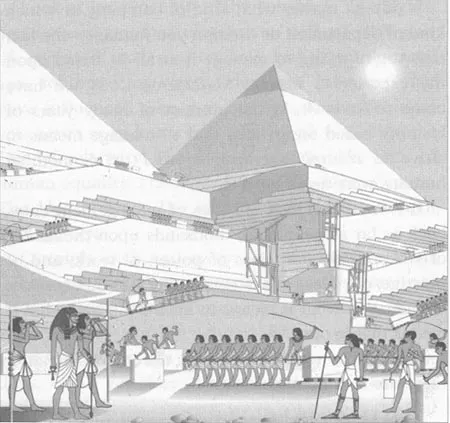

The idea of the Manager is best typified by the illustration on the following page. It shows the pyramids being built. It shows the workers, their immediate Managers (today we call them supervisors), and the supervisors’ Managers. The supervisors are the guys with the whips and chains. The workers, in case it isn’t obvious, are the ones moving 400 billion tons of monster rock into place to build the pyramid for their great leader.

As the story goes, the very entrepreneurial leader of this gambit was lying around one day eating grapes and cavorting with women and boys when it suddenly occurred to him that he wouldn’t get to do this forever. That, at some point, he was going to die. “There must be some way to memorialize my magnificence,” he thought, “to make me immortal.” He wondered for a moment, then exclaimed, “What about a great big rock or temple, or—I’ve got it—what about a pyramid! An Emperor’s tomb. The biggest box anyone has ever been put to rest in. Bigger than anything anyone has ever built before. Bigger than a mountain.”

Ah, the grapes must have tasted sweeter as this idea—this bigger-than-any-idea-he-had-ever-had-before idea—took form in his mind. And from the moment the idea possessed him, he lived with that picture in his mind, he ate with it in mind, he slept with it in mind. No matter what, he had to do it!

So he gathered together his ministers (the senior management team), his overseers (the middle management team), and his foremen (the supervisors). And he placed the execution of his precious Vision in the hands of the guys who carried the whips and chains and knew how to use them.

So the Emperor sucked on grapes while the senior Managers worried about the numbers and the middle Managers walked around with clipboards and made not-so-idle threats. And the subordinates, by the millions, dug up rock, inhaled rock, ate rock, spit out rock, swallowed rock, picked up rock, and moved rock toward its final destination, where they hoisted rock, shifted rock, lifted rock, balanced rock, and placed rock upon rock upon rock upon rock. Meanwhile, miraculously, the grand pyramid rose, out of sand, out of an idea as thin as the air between the ears of the Emperor, manifested from virtually nothing into the most magnificent something anyone had ever seen.

And in fulfilling the dreams of one man, other men began to dream of other grand ideas. If he could do that, they reasoned, why couldn’t we do this? And that? And some other thing?

Like build the Great Wall of China. Or stage the Russian Revolution. Or create McDonald’s, or Microsoft, or CNN?

All of these, built in the same way as that very first pyramid.

The Plight of the Modern Manager

Today’s Emperors—we call them visionaries—rely upon a “new” model of management, which, while not really any different from the old model, does feature a couple of new twists: one is the technological revolution, which is forcing us all to do more faster; the other is the aftermath of reengineering, which is forcing us to do more with fewer people.

No wonder modern-day Managers are so depressed.

In the absence of “elbows and shoulders,” the people who moved the rock and were lost to downsizing, Managers became the Emperors’ lackeys. They embraced the challenge in earnest. They bought business books and management treatises written by consultants and academics who translated the realities of the real world. They attended management trainings and seminars and workshops, to hear themselves being applauded as the twentieth century’s new profession. Like physicians and attorneys and the clergy, Managers felt they were making a significant contribution to society and to the world at large, and business was fast becoming a new church. They called where they worked a “culture.” They spoke of “quality” and “core values” and “missions.” They talked about uncovering the “soul” of the organization. They talked about “spirit” and “meaning,” and sent their people to “vision quests.” They learned about leadership and went to Utah to learn to distinguish themselves from ordinary Managers as extraordinary leaders. They learned there was a science to it all. That leaders are made not born. That you could learn the seven essential skills, or the six effective habits, or the trick of becoming a one-minute Manager. They listened in earnest and learned all the tricks, and still nothing changed, because the Managers—and the gurus who were teaching them—were only treating the symptoms, not the causes.

Meet Jack, a Guy Just Like You

Jack was one such Manager. Raised by his mother, a teacher, and his father, a loyal organization man, Jack grew up with management. His father’s boss came over once a week for dinner. His mother socialized with the wives of his father’s coworkers. To him, business equaled a blue suit and white shirt, eight-hour days, and dinner on the table by five for his father, who’d worked at the same corporation his entire life.

There had always been a kind of allure about management for Jack, and his father recognized this early on. He had egged Jack on even as a small boy, taking him to the office on occasional Fridays, introducing him to his staff and encouraging him to “manage” rather than just “play” store when Jack and his friends got together after school. An inquisitive student, Jack scored straight As throughout intermediate and high school, and went to Stanford University, where he majored in business and management. At the same time, he took a job as an assistant store Manager at the campus bookstore to help pay his way through school. He couldn’t have been more thrilled.

He liked working as much as studying, that was certain. But the job wasn’t what he’d thought it would be. The long hours and the mindless stacking were bad enough, but then there was Cody, the Manager of the bookstore, who had a way of making Jack feel bad. First, he’d told Jack he was lucky to have a job, that Cody was providing him with the best education he’d ever get. As time went by, Jack began to feel more like a slave to the whims and whimsy of Cody, rather than a valued employee. No matter how hard Jack worked, Cody raised the bar, and his evaluations of Jack’s performance often had little to do with the work actually being done. In spite of this, Jack stuck it out. He needed the money to get through school, and the devil he knew, he thought, was surely better than the devil he did not. He had also learned “not to be a quitter” from his father, who’d said, “Your career is who you are. It’s the path to financial, psychological, and cultural security.”

Jack eventually graduated from school, got married, and got his first “real” job, as an assistant sales Manager of a major department store. He was glad to have left Cody and the bookstore behind, and happy to throw himself wholly into the first illustrious step of his career. This first step on the corporate ladder wasn’t accomplished with great flourish, however; rather, it was a quiet, thoughtful, and unassuming one. The store was close to the small apartment he had rented with his new wife, Annie; the pay was good, and the challenge, great. Jack resolved to give everything he had—and then some—to succeed in his first real corporate role.

And succeed he did. He did what was asked of him. He pushed the limits of his personal life to accomplish tasks that were beyond the duty of an assistant sales Manager. He gave up his time, often studying into the night and working long hours every day. He even moved with his now growing family, three times during that first step, once across country, once to the Midwest, once back to where he’d started from. He became someone who could be depended upon to do the job well.

As reward, he was promoted three times, received more perks, benefits, salary, and bonuses, and gradually moved up the corporate ladder. Unbeknownst to Jack, however, his life was fast becoming a cliché. But he truly didn’t notice—in part, because he was just too busy, but also because deep down inside him there resided an earnestness he couldn’t account for, a need to be needed, to be relevant, to play a serious part in the life around him. Deep inside he thought he was doing exactly the right thing. He saw the signs, after all. The company grew. His people respected him. He felt a certain sense of growing dignity.

Jack even felt a sense of purpose in what he was doing. He identified with the company, his bosses, and their goals, which, he believed, were his goals too. And for a while, perhaps, they genuinely were. But to a large extent, Jack’s so-called happiness was dependent on a few very significant things: the largesse—or lack thereof—of his superior, whose own Vision all but ruled Jack’s working life; Jack’s own idea of management, which was influenced by many factors, including his father and his first boss; and Jack’s lack of real motivation to do anything beyond what others expected of him.

When I first met Jack, as a Manager at my own company, The E-Myth Academy, he’d just about had it with management, period. As luck would have it, I happened upon a visibly despondent Jack when I was “walking around” my business, as Tom Peters had exhorted me to do. Jack was pacing outside of another Manager’s office as he waited for her to get off the phone. With his face red and shiny, I could tell he was about to explode.

“What’s going on with you?” I asked him.

“Uh, oh…nothing I can’t handle,” he replied nervously.

“You look to me like a guy who’s harboring a lot of pent-up frustration.”

“Ah, no…it’s just…” He looked away.

“It’s okay,” I replied. “I see guys like you all the time, although usually in other people’s companies. But in my company it’s a lot harder to see, so I probably avoid it like the plague. What do you say we grab some lunch and get some of this negative energy out into the open so we can both take a look at it in earnest?”

Jack looked both terrified and relieved.

“Okay,” he replied. “Let me get my coat.”

I took Jack to a favorite coffee shop not far from The Academy offices in Santa Rosa, where we ordered coffee and sandwiches. Looking around nervously, he shifted uneasily in his seat. He was obviously not at all comfortable with the idea of discussing whatever was bothering him with me, the Emperor of the organization for which he worked. And I was intrigued, given how much experience I’d had helping other organizations and Managers solve their problems, to find a perfect specimen in my own backyard.

I decided to relieve him of the silence that stood between us.

“So, Jack,” I started. “We don’t know each other very well, but I’d like to help with whatever’s bothering you, if I can. So why don’t you start off by telling me what that might be.”

“It’s nothing, really,” he replied. “I mean, nothing that I haven’t dealt with many times before.”

“Is it a particular project? A coworker? A client?”

“No, no, nothing like that. It’s me…really, I’ll be fine.”

I had suspected all along that the look of utter exasperation—which comes only from an intense, accumulated emotional reaction—was the result of something having to do with Jack, not a client or coworker. In fact, my guess was that he had just about had it with his job as director of field operations. So I asked him.

“Is it your job that’s bothering you?”

He brightened with recognition for a moment; then a cloud came over his face. He clearly wasn’t sure what to say.

“It’s okay, Jack. Forget for the time being who you think I am. For the moment, just pretend to yourself that I’m here as a consultant and friend. Tell me what’s been going on.”

He lifted his glass, took a swallow of water, and began.

The Emperor Meets the Emperor

“The trouble is, I’m not exactly sure what’s wrong,” Jack star...