CHAPTER 1

The Sorry Places We Live

Boredom sets in first, and then despair.

One tries to brush it off. It only grows.

Something about the silence of the square.

—MARK STRAND, “Two de Chiricos. 2. The Disquieting Muses”

The fact that a man does not realize the harmfulness of a product or a design

element in his surroundings does not mean that it is harmless.

—RICHARD NEUTRA, Survival Through Design

The headline to one of my early essays in architecture criticism, published in The American Prospect, was written by my editor, not by me. But when he sent along the galleys, it was clear he thought I’d pulled no punches: “Boring Buildings,” the title thundered. In the subhead I could almost hear my own plaintive voice, wondering “Why Is American Architecture So Bad?” Since that essay’s appearance fifteen years ago, our country’s and our world’s political, social, and economic landscapes have much changed. The events of 9/11 ushered in a far more perilous and increasingly self-conscious era. The Internet and digital technology changed how we communicate and how we shop, the nature of our right to privacy and even our sense of ourselves; they also rapidly accelerated economic integration and made globalization an economic, social, and cultural reality. Even so, fifteen years later, the indictment announced in that headline rings true, and not only in the United States.

Four Sorry Places

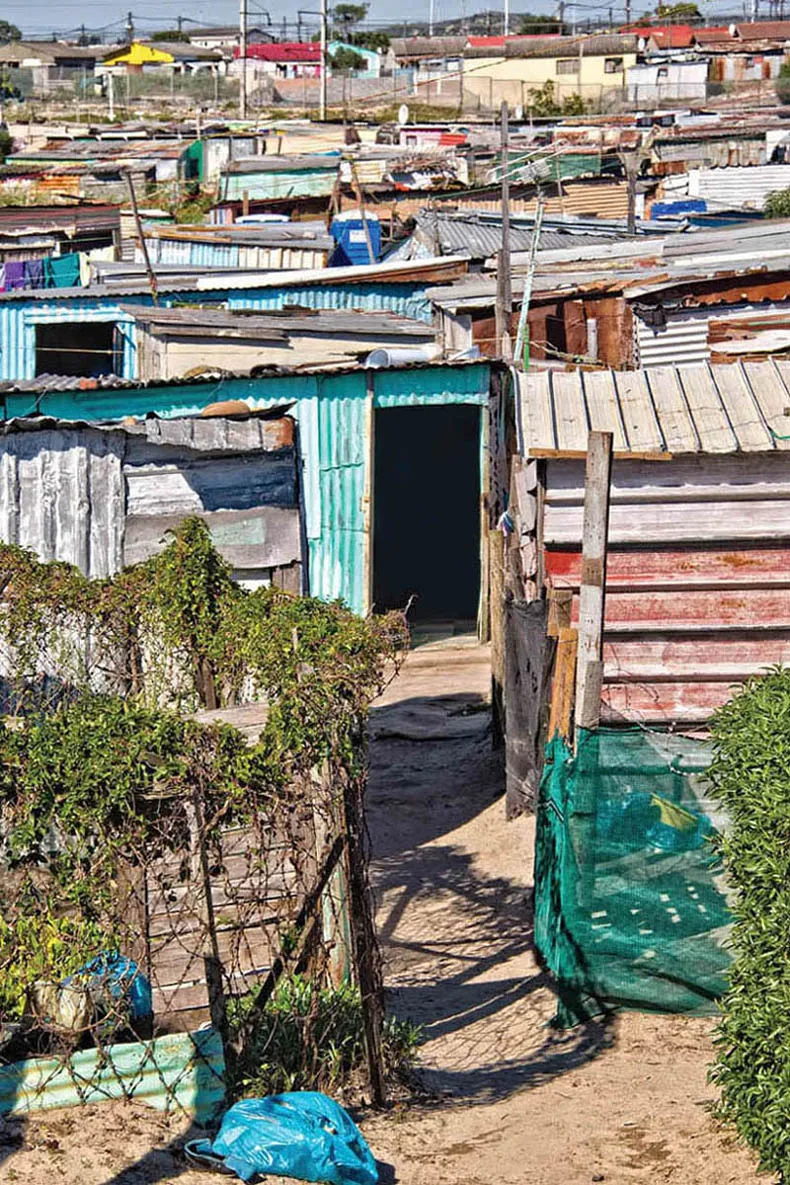

In the places we live, beggary casts a wide net, as four very different kinds of settings exemplify. The shacks inhabited by many millions of people on every continent except Antarctica make the case that built environments lacking in any sort of considered design greatly contribute to the degradation of human life. If we consider such slum dwellings in relation to the developer-built single-family houses that hundreds of millions more call home, however, we see that lack of resources constitutes only one part of the problem. Then, if we examine both alongside the design of a resource-rich high school in New York City, it becomes clear that people’s failure to accord their built environments sufficient priority plays an important role. And if we take all that information and synthesize it with what we can learn from an art pavilion in London designed by a Pritzker Prize–winning architect, Jean Nouvel, we see that even with ample resources, good intentions, and well-placed priorities, things go wrong. These four examples of built environmental beggary show how pervasively poor our built environments are, and suggest the complex reasons why. They also belie what slum dwellings by themselves might suggest: money, or lack of it, constitutes only a small part of the challenge.

Slums are an example where resources truly are scarce. In Haiti, one and a half million people lost their homes in the devastating 2010 earthquake, and many lived in the aftermath and continue to live in encampments of makeshift, temporary shelters. Among the thousands of heartbreaking images documenting the Haiti disaster was this photograph of a huddling row of shanties clutching to the median strip of Route des Rails in Port-au-Prince, where entire families inhabit tarp-covered one-room shacks with dirt floors. Cars and trucks rumble and speed by. No electricity. No plumbing. No privacy. No quiet. No clean air to breathe, fresh water to drink. Just unlucky people trying to maintain their rectitude and dignity in a built environment that pulls them down every day.

Life on the Route des Rails one year after the catastrophic 2010 earthquake, Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Ruth Fremson/The New York Times.

Although this photograph depicts people struggling to survive in the wake of a singularly catastrophic event, the circumstances in which they live are unusual in only two ways: cars pass through this linear settlement very quickly, and fabric tarps cover their shacks instead of the usual corrugated metal, scraps of plastic, thatch, or rotting plywood or cardboard sheets. These Haitian shacks otherwise resemble their analogues: favelas in Brazil, bidonvilles in French-speaking countries such as Tunisia, townships in South Africa, shantytowns in Jamaica and Pakistan, campamentos in Chile, and to use the most generic name among the dozens of such appellations in usage, slums around the world. The names, the materials from which they are built, the destitution of shelter they provide, the degree of desperation within differs depending upon economy, culture, climate, and continent. But the basic living arrangements are the same. One, two, even three generations jammed together with their belongings in one or two insalubrious rooms that lack the basic infrastructure of power and sanitation.

Thirty percent of all South Asians, including 50 to 60 percent of the residents of India’s two largest cities, Mumbai and Delhi, live in slums; estimates of the population density of Mumbai’s Dharavi slum range widely, from between 380,000 and 1.3 million people per square mile—five to nineteen times that of Manhattan. Sixty percent of sub-Saharan Africans inhabit slums. Four million people dwell in the largest slum in the world, draped across the outskirts of Mexico City. All told, one out of every seven of the planet’s people, totaling one billion, and one-third of all urban dwellers call such places home. The Housing and Slum Upgrading Branch of UN-Habitat predicts that by 2030 the number of people living in slums will more than double, as slums are “the world’s fastest-growing habitat.”

How might a child growing up in a leaky shack in Port-au-Prince or Mumbai or Lagos be affected by the physical circumstances of his surroundings? Children who inhabit chaotic, densely populated homes exhibit measurably slower overall development than do children raised in more spacious quarters. They underperform in school and exhibit more behavioral problems both in school and at home. An acoustically uncontrolled space too tightly packed with people, with little privacy, correlates with disorder, explaining why crowded homes are associated with higher rates of child psychiatric and psychological illness. We know that the degree of control a child feels he has over his home environment is inversely related to the number of people per square foot who live there, and a diminished sense of control compromises a child’s sense of safety and autonomy, of agency and efficiency, and hence likely of motivation.

Slum dwelling in Africa. iStock.com/Delpixart.

This is just the most obvious way that the design of a shanty house compromises people’s lives. Overcrowding, lack of privacy, and environmental noise diminish a child’s capacity to manage her emotions and hinder her ability to deal effectively or even to cope with life’s challenges. So not only do slum-dwelling children enjoy fewer opportunities, but they are also less capable of taking advantage of the opportunities available to them. Even if an adult raised from birth on the Route des Rails unexpectedly encountered sudden good fortune, she would likely struggle, and struggle more than a woman whose childhood had not been permeated with such built environmental deprivation and degradation. A person’s experience of growing up in challenging and impoverished circumstances results in lifelong diminished capabilities.

It’s not only such patently deprived places, lacking in any sort of design, that diminish people’s well-being. Resource-rich middle-and upper-middle-class housing developments in the United States prove that. Consider two new ones that differ greatly in locale, price point, consumer base, and design. Lakewood Springs is in Plano, Illinois, a suburb approximately one hour’s drive west of Chicago. A relatively small middle-class development, its homes are arrayed on the paper-flat land that constitutes much of America’s midwestern plains. Stylistically, the architecture at Lakewood Springs reinterprets the traditional midwestern farmhouse in two basic models, with low-slung, single-story homes and two-story townhouses alternating along cul-de-sacs and gently curving streets. The second settlement can be found in Needham, Massachusetts, a development of McMansions. Homes here run larger, and though their configurations vary more widely, they hew stylistically to what might be termed Realtor Historicism.

Middle-class developer-built suburban home. iStock.com/Paulbr.

Size and price differences notwithstanding, the $200,000 house in Plano, and the $1 million house in Needham, share many basic features and problems. Each unit accommodates a single nuclear family. In spite of clear demographic trends toward the aging of our population, in spite of the growing variability of family composition, there is no place at Lakewood Springs or in Needham for elderly parents or for the disabled incapable of living on their own. Within each development, lot sizes are more or less identical (bigger in Needham), with houses plunked down at the lot’s midpoint, sandwiched between a front and back yard. Residents enter their homes through the garage, yet “front” doors gaze sorrowfully onto the street while “front” yards go largely unused. The layout of the homes and the scarcity of locally accessible services afford inhabitants limited opportunities for spontaneous social interaction.

Both in Plano and in Needham, these homes are tossed together from off-the-shelf materials using simple construction techniques requiring little skilled labor. Their environmentally suspect materials are cheap and thin; their timber harvested with little regard for sustainability; the PVC piping threaded through them leaching volatile organic compounds into the ground and the water the inhabitants drink; and gypsum walls that visually demarcate one room from the next offer but scant acoustic or thermal insulation. Carelessly standardized room arrangements and stock floor plans result in poorly placed windows and rooms with little attention to where the house happened to end up on the lot. No heed is paid to prevailing winds or to the trajectory of the sun’s rays. For example, in one house, the living room might be dark, while in another, it might blaze with sunlight; some bedrooms might be too cold, others too warm. Efficient thermostats and artificial light cloak poor design.

Higher-end developer-built surburban home. iStock.com/Purdue9394.

Okay, you may think, so these middle- and upper-middle-class housing developments aren’t great. Surely the homes and institutions and landscapes that serve more affluent people are better? Some are, but many more are not. Take my own experience with trying to find a school for our son. A few years ago, preparing to move to New York City from out of state, my family visited a number of private schools in Manhattan and Brooklyn in search for the right fit for our soon-to-be high schooler’s challenges and considerable abilities. Most families would be happy to send their children to a certain school in upper Manhattan. This pre-K–12 school occupies a collection of buildings abutting one another on a leafy side street; its entrance sits in a heavily shadowed, deeply sculpted, Richardsonian Romanesque masonry pile of earthy tans and reddish browns. But its high school, located in a newer building perhaps forty years old, looked a little less and a little more like a hundred suburban high school degree factories. Its many classrooms, below-grade, were rectangular cinder-block grottoes, with industrial-grade wall-to-wall carpeted floors and ceilings lined with standard-issue white acoustic tiles. Furniture for the classroom consisted of metal desks and chairs. Ninth-, tenth-, and eleventh-grade classrooms lined a narrow linoleum-tiled internal corridor, with sound bouncing around and off walls like so many balls on a crowded playground.

It got worse. Even though one of an adolescent’s principal challenges is to learn how to navigate an increasingly complex social world, only one large space explicitly facilitated this important pursuit, an informal gathering area that students called the Swamp, a nickname that conveys, presumably, not the room’s physical appearance but a student’s experience there. Forlorn castaway sofas floated in a cramped afterthought of a corridor, an unwelcoming muskeg that offered a prix fixe menu of social opportunities: being or not being part of a large, amorphous group. In the Swamp, teenagers buzzed like dragonflies and crickets and locusts, a deafening din.

Yet research clearly demonstrates that design is central to effective learning environments. One recent study of the learning progress of 751 pupils in classrooms in thirty-four different British schools identified six design parameters—color, choice, complexity, flexibility, light, and connectivity—that significantly affect learning, and demonstrated that on average, built environmental factors impact a student’s learning progress by an astonishing 25 percent. The difference in learning between a student in the best-designed classroom and one in the worst-designed classroom was equal to the progress that a typical student makes over an entire academic year. Students participate less and learn less in classrooms outfitted with direct overhead lighting, linoleum floors, and plastic or metal chairs than they do in “soft” classrooms outfitted with curtains, task lighting, and cushioned furniture, all of which convey a quasi-domestic sensibility of relaxed safety and acceptance. Light, especially natural light, also improves children’s academic performance: when classrooms are well li...