1

Introduction

Background

Many scholars focus on the country allocations of bilateral and multilateral donors (Feeny and McGillivray 2008; Collier and Dollar 2002; Hansen and Tarp 2000; Lensink and White 2000; Burnside and Dollar 1997). Many also research the geographic choices of NGOs at the sub-national level (e.g. Barr and Fafchamps 2005; Fruttero and Gauri 2005; Bebbington 2004; Zeller et al. 2001). However, hardly any research has been done on the country choices of international NGOs, the recent work by Nancy and Yontcheva (2006) being a notable exception, or on the determinants of these choices. This is surprising since these international NGOs have by now a combined budget of some US$26.9 billion.

Besides the increased size of international NGOs, there are also other recent development whose relationship with geographic choices are not evident, such as the sharp increase in the number of international NGOs, their intensified competition for funding, and their heightened financial dependence on official aid agencies.

The number of international NGOs runs into the thousands. Umbrella organizations of international NGOs in the OECD countries had more than 2,500 members in 2008. Coordination among organizations is known to be difficult, especially when large groups are involved (Brett 1993). It is not clear to what extent international NGOs are ensuring an even distribution of their activities, or rather, are displaying herding behaviour. An obvious research question is thus whether the multiplication of the number of international NGOs hampers geographic coordination among them.

Heightened competition for funds among international NGOs is another factor that influences the behaviour of international NGOs (Schulpen and Hoebink 2001). Back donors (official aid agencies) increasingly work through competitive tender systems, in which NGOs vie for contracts. Various scholars and international NGOs have claimed that this process of ‘marketization’ erodes their capacity to take risks and engage in the poorest areas (e.g. ECDPM 2004a). However, claims that international NGOs made more audacious geographic choices in the past, and have abandoned those because of competitive pressures, have yet to be verified and could be the subject of new research.

Over the past decades, official aid agencies have worked increasingly with and through international NGOs (Wang 2006; Edwards and Hulme 1998). Many donors, including the United States, Norway and the Netherlands, provide more than 20 per cent of their aid through international NGOs. Back donors argue that they channel aid through international NGOs because they are able to reach people who are beyond the reach of official donors because they live in countries characterized by endemic state corruption (UN Millennium Project 2005). Yet, the underlying assumption that international NGOs complement the efforts of official aid agencies and that they are effective in those types of countries has never been tested, and thus poses another research question.

Since back donors increasingly choose to work with and through international NGOs, the majority of them now receive more than half their budget from official donors. Many authors have strongly criticized this situation, casting doubt upon whether international NGOs are worthy of the name ‘non-governmental’ (e.g. Smillie 1997; Wallace 2000). Because of the growing infusion of public funds into international NGOs it is unclear whether they have become the executing subcontracting agencies of Northern governments or whether they are still able to make autonomous policy and country choices. This is yet another area for research.

There are various angles from which to analyse the ramifications of the increase in size and number of international NGOs, the heightened competition among them and their growing financial dependence on official donors. The operating procedures of international NGOs could be analysed, for instance, to ascertain whether their working practices are starting to resemble those of government agencies, as Fowler (1995) and Feldman (2003) suggest. Alternatively, it could be analysed how such increasingly large organizations create knowledge, as Porter (2003) and Tvedt (2002) have done, or whether they coordinate their efforts. This could be researched by determining to what extent international NGOs work on complementary themes, which Gauri and Galef (2005) did for Bangladesh.

This research takes yet another angle. It seeks to explore the implications of the trends discussed on the country choices of international NGOs, which has so far been uncharted territory.

Research outline

Independent evaluations of the long-term impact of international NGOs are still relatively rare. However, there are indications that international NGOs can have a substantial and lasting effect on poverty in the countries in which they work. Using panel regressions for 58 countries, Masud and Yontcheva (2005) demonstrate that aid from international NGOs contributed to a reduction in infant mortality rates during the 1990s. Bradshaw and Schafer (2000) find that growing involvement of international NGOs in a country leads to stronger economic development, more widespread provision of clean water and other facets of human development. Roberts (2005) corroborates these findings. He shows that the level of human development increased more in countries with strong ties to international NGOs in the early 1980s, than those with weaker ties, when controlling for other factors, in the subsequent two decades. The important contribution of international NGOs to pushing debt cancellation to the top of the G8 agenda has been widely documented, as well as the effects of these debts reductions on poverty in a number of developing countries (e.g. Hertz 2004; Hinchliffe 2004).1

This research thus refrains from questioning the ‘raison

’ of international NGOs (Hearn 2007; Petras 1997). It takes their existence and the potential benefits of their work as a given, and analyses critically one aspect of international NGOs: their country choices. In a sense, this research thus falls within the type of research of Mosse (2005), who shows that a critical research approach towards international aid actors can produce interesting insights in how aid policies and practices (co)-develop.

The following three questions guide the research:

- What are potential determinants of the geographic choices of international NGOs?

- What explains the geographic concentration of international NGOs?

- What are the academic and policy implications of the research findings?

The research is divided into three parts, which each focus on one research question.

Part I: Mapping and testing potential determinants of the geographic choices of international NGOs

The first part of the research asks: what are determinants of the geographic choices of international NGOs? The following potential determinants are mapped and tested in Chapters 2 and 3:

- poverty levels in recipient countries;

- governance situation in recipient countries;

- preferences of back donors;

- processes of concentration (the preferences of other NGOs);2

- NGO specific missions.

Part II: Explaining the geographic concentration of international NGOs

The second part asks: What can explain the process of geographic concentration of international NGOs?

- Can an evolutionary economic geography approach help explain the geographic concentration of international NGOs (Chapter 4)?

- Can poor country images explain why international NGOs exclude certain countries (Chapter 5)?

- Can differences in the funding situation of international NGOs, for example due to competition among international NGOs and their level of financial dependence on back donors, explain differences in concentration of international NGOs (Chapter 6)?

Part III: Analysing the implications of the geographic choices of international NGOs

The last part of the research asks: What are the academic and policy implications of the research findings?

- How does the concentration of international NGOs affect cooperation between them (Chapter 7)?

- What are the academic and policy implications of the findings on the five determinants (poverty and governance levels in recipient countries, the importance of the preferences of back donors, geographic concentration, NGO-specific mission?) (Chapter 8).

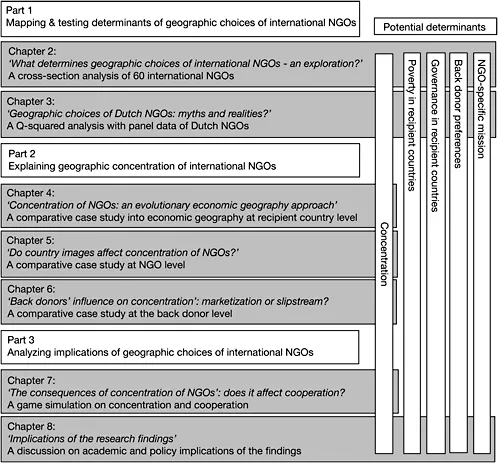

Figure 1.1 illustrates how the different parts and chapters are linked. Part I (Chapters 2 and 3) focuses on mapping and testing five determinants of the geographic choices of international NGOs. This shows that the concentration of international NGOs is a prime determinant of their geographic choices. Part II (Chapters 4 to 6) subsequently analyses why this geographic concentration of international NGOs emerges. Each chapter focuses on a different level of the aid chain: Chapter 4 looks at recipient countries; Chapter 5 at international NGOs; and Chapter 6 at back donors. Part III (Chapters 7 and 8) builds on the two previous parts and assesses the findings of the research. Chapter 7 focuses specifically on the consequences of the concentration of international NGOs on cooperation among them in a recipient country. Chapter 8 discusses the academic and policy implications of the findings regarding the five determinants of the geographic choices of international NGOs that were mapped and tested in Part I.

Research approach

The five determinants that are the focus of this research (poverty levels, governance situation, preferences of back donors, concentration, NGO specific mission) by no means represent all potential determinants of the geographic choices of international NGOs. They are sometimes not even the pervasive drivers of such choices. However, they are cited frequently in the literature on the geographic choices of international NGOs. Furthermore, initial empirical research conducted for this study shows that this set of determinants provides a wealth of new and occasionally contradicting findings.

Figure 1.1 Analytic map of the research

‘Poverty in recipient countries’ is often considered the prime determinant of the geographic choices of international NGOs. Their decisions are therefore often analysed from this perspective (e.g. Nunnenkamp 2008; Dreher et al. 2007; Nancy and Yontcheva 2006). International NGOs are thought to be unsusceptible to geo-political pressures and therefore in a position to target the poorest parts of the world. An exploratory analyses of the data compiled for this research points in a different direction, however.

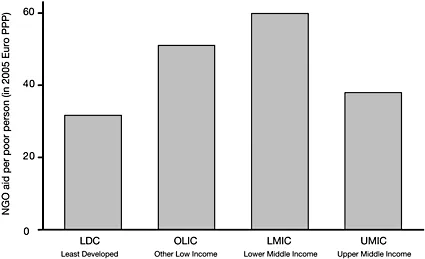

Figure 1.2 seems to suggest that international NGOs do not target the poorest countries and that they allocate more aid per poor person in Middle-Income Countries than in the poorest countries.3 This relationship will be explored further in Chapters 2 and 3.

The second potential determinant included in this research is ‘the governance situation in a recipient country’. As discussed in Chapter 2, the academic and policy literature suggests that international NGOs are effective in countries where other governmental actors are not, notably in countries with poor governance (UN Millennium Project 2005; Edwards and Hulme 1998; World Bank 1998). However, a preliminary scan of the data compiled for this research shows that this assumption may not hold true.

Figure 1.2 Figure 1.2 NGO aid per poor person over DAC classification

Source: World Development Indicators (2006), OECD (2007) and Koch, own data.

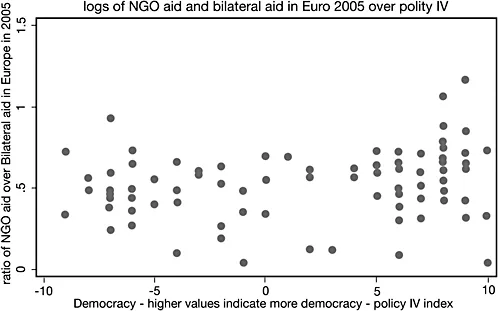

Figure 1.3 appears to suggest that there is no relationship between a country’s level of democracy and its ratio of international NGO aid to bilateral aid. A country like Zimbabwe, which sits on the left side of the graph, receives the same ratio of international NGO aid to bilateral aid as a country like Ghana, which sits on the right side of the graph. This figure highlights a potential disconnect between the claims made in the literature and the actual geographic choices of international NGOs that deserves to be analysed.

The ‘preference of back donors’ is the third angle from which to analyse the geographic choices of international NGOs. It is heavily contested whether international NGOs can be considered truly non-governmental or not (e.g. Ferguson 2006; Kalb 2005; Biekart 1999; Fisher 1997). Some argue that international NGOs are mere implementers of the policies of their back donors. Others argue that international NGOs operate autonomously even though a large share of their budget is covered by back donors (Nancy and Yontcheva 2006). This research aims to contribute to this debate through a systematic analysis of the influence of back donors on the geographic choices of international NGOs.

The fourth determinant covered in this research is the concentration of international NGOs. The academic literature includes relatively little on the clustering of non-profit actors, Bielefeld and Murdoch (2004) being the exception. However, the data gathered for this research reveal that the geographic choices of international NGOs are characterized by strong patterns of concentration.

Figure 1.3 Ratio international NGO aid to Official Development Assistance over Democracy

Source: Koch, own data.

Note: The OECD/DAC data on bilateral data also include, in some instances, aid to and through NGOs. It appears that the DAC includes decentralized funding to NGOs in the country-wise breakdown of bilateral aid through NGOs. This could potentially lead to a bias in this graph, as arguably embassies and decentralized aid agencies in poorly governed countries provide relatively more aid to NGOs than to governments. However, an in-depth analysis of one of the major bilateral donors, the Netherlands, showed that there was no relationship between decentralized NGO funding and governance levels. Furthermore, the funding available for NGOs through decentralized funding is much smaller than the funding available for NGOs at the headquarters level.

Figure 1.4 illustrates how the activities of 61 of the world’s largest international NGOs are concentrated.4 The map shows per capita NGO expenditure (in Euros) in developing countries, with countries with a darker shade receiving more NGO aid per capita.

In 2005, the combined budget of the 61 international NGOs included in the s...