![]()

1 Introduction

Even though many parts of the developing world are in the midst of an information technology (IT) revolution which affects firms, households and all sectors of the economy, one would not think it from reading the scant academic literature on the topic. Tellingly, for example, there is little or nothing to be found on the subject in the latest versions of the major textbooks on economic development. Academic books are few and far between, and only a small number of journals cited in the Social Science Citations Index (SSCI) is dedicated to the topic. All in all it seems that academia has not kept up with developments on the ground, which include most notably widespread penetration of mobile phones even in some of the poorest countries (see below). Apart from that discussed in Chapter 12, for example, there is no adequate measure of the leapfrogging underlying the widespread penetration of mobile phones.

The problem is especially severe in economics, which, among all the relevant academic disciplines, has been least in evidence in the literature. Yet, as this book seeks to show, it has a great deal to offer in the debates over information and communication technologies (ICT) for development. This is true at the level of micro- as well as macroeconomics.

What is also missing is a systematic attempt to compare the measures of different concepts of the digital divide (see definition below), though, as I will show, they sometimes produce completely different results. Nor are there many attempts to assess, with any degree of rigour, popular policy issues such as low-cost computers, leapfrogging or bandwidth expansion. In seeking to redress these and other weaknesses of the literature, this book focuses on issues related to international inequality and national poverty, including the connections between them. Two parts deal with the former while the third and largest part is concerned with IT and national poverty in developing countries. A common theme in this book is that relying on Western concepts and measures is a flawed way of understanding much that goes on in the relationship between IT and development (in the developed world, for example, users of IT usually own their own technology, but this is not at all the case in developing countries, where users much more rarely own the hardware that they use, especially in the case of the Internet). Sharing is one important way in which the gap between use and ownership is breached (especially in the case of mobile phones, as described in Chapter 4).

International inequality and national poverty

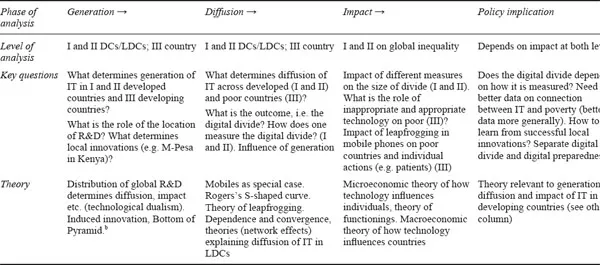

My task in this introductory chapter is first to compare the different parts of the book and then to compare the chapters within each part with one another (allowing for connections between them). Both of these tasks make use of the entries shown in Table 1.1. These entries, one should note, are not at all meant to constitute an exhaustive summary of the book. Rather, their goal is to give the reader a sense of its main directions and focus. For this more modest objective Part I and Part II on international inequality are separated from Part III (national poverty).

In terms of rows, one can see first that they define the level at which the analysis takes place, whether that of an individual country or between countries. The second row looks at major questions at each stage of the analysis; and in answering these, one is concerned in the last row with the theories that are pertinent to each phase. For example, the s-shaped curve approach to diffusion of new technology mentioned in the last row and second column of the table throws light on the question posed in the row above about the determinants of diffusion across and within developing countries. What also needs to be considered in this context is that throughout the table there may be substantial differences between mobile phones and the Internet. Whereas, for example, use of the former has grown at unprecedented rates in developing countries, the same cannot be said of the latter, whose penetration continues to lag behind.

A major underlying recognition in Table 1.1 is that the four columns – generation, diffusion (penetration), impact and policy – are inter-connected; they are part of what is known as the project cycle. Consider, for example, a technique that is generated to fit in with the socio-economic circumstances of rich rather than poor countries. This is likely to mean in the diffusion stage that the new technology benefits the former rather than the latter countries. And this in turn will likely have an impact that widens global inequality and does very little for national poverty in the developing countries. An opposite story, however, may be told of an innovation that is generated in and for a poor country. Consider, for example, M-Pesa, a mobile banking solution in Kenya. The scheme allows those without a bank account (some of whom presumably are relatively poor), to ‘transfer funds as quickly and easily as sending a text message’ (BBC 2010). In the language of Part III, M-Pesa would clearly be described as an appropriate technology.

In terms of the crucial impact stage (third column), I have singled out three of the most important issues. The first concerns the impact of the measurement of the digital divide on its size (Parts I and II). The second is about the influence of technology on poor inhabitants of developing countries (Part III) and the final issue deals with the special case of leapfrogging’s influence on such persons (Part III) and countries more generally.

Parts I and II: the digital divide and digital preparedness

Chapter 2 takes as its point of departure the basic recognition from Table 1.1 that the generation of new technology influences the speed of diffusion in different countries, which in turn shapes the impact of the policy and its implications. The problem, as already noted, is seen as being the result of a concentration of research and development (R&D) in the developed countries (though the performance of China is beginning to ameliorate this issue). For what then occurs is a focus of R&D on the demands of these rather than poor countries. This problem is sometimes referred to as technological dualism (Singer 1970) and it has implications for the other phases of the project cycle as well. In terms of impact, for example, the gains of R&D tend to be biased in favour of those countries with relatively high income and skills and an advanced infrastructure (though this is much more true of the Internet than mobile phones).

Table 1.1 Outline of the book

Notes

I, II and III refer to the different parts of the book. A similar idea is expressed in Chapter 2 but not as fully;

b See Prahalad (2004).

The remaining chapters in Parts I and II focus mainly on the measurement of the digital divide and what it implies for developing countries. The standard measure, for example, is to take the ratio of IT in the developed countries to that in the less-developed countries (LDCs); according to this ratio the digital divide has been falling over time and continues to fall. Against this is a measure that reflects a world distribution of Internet users with different income levels, which makes particular reference to those living in poverty. The point is that the conventional measure of the digital divide provides us with little or no information on the divide between citizens of the world, who are differentiated, among other ways, on the basis of income level. Such information would allow us to trace changes in the degree of world inequality in Internet use among individuals with different income levels.

Making the transition to this concept of the digital divide entails weighting by country size (as Sala-i-Martin 2006 has done in the context of world income inequality). Given the fact that the country which experienced the most rapid rise in Internet use between 1994 and 2004, China, also happens to be the most populous and was located at the time among the poor developing countries, the effect is to sharply reduce the relative to the standard measure (for example, whereas the unweighted measure is around 8 to 1, the weighted version almost eliminates the distinction between rich and poor countries).

Similarly, though it is not often mentioned in the literature, the most common way in which poor people gain access to mobile phones and the Internet is via sharing rather than ownership of the technology. I am thinking here of, for example, schemes like Grameen Telecom, informal sellers of phone time on street corners in Sub-Saharan Africa, kiosks in India, telecentres and simple sharing with family and friends. Some of my calculations in Chapter 4 suggest that when sharing is taken into account, the digital divide may be greatly reduced or eliminated altogether.

Note that the gains from sharing mobile phones do not accrue in only economic form. In relation to Grameen Telecom, for example, von Braun et al. (1999) show that women owners of phones in the village enjoy an increase in empowerment and a rise in status. Goodman’s (2005) study of South Africa and Tanzania found that social capital was increased as a result of mobile adoption and manifested itself in greater participation in group activity and social networks. Note too in Chapter 18 that Sen’s concept of functionings is often a better measure of poverty than purely economics-based measures.

Chapter 3 is similar to Chapter 6 in that it looks within the aggregate known as the developing world at the characteristics of individual countries within the group. In particular, research shows that some developing countries are closing the digital divide while others are not. What have not been investigated are the implications for the digital divide of the differential experience of individual developing countries. The issue is whether the digital divide is narrowing in relatively rich or in poor developing countries. In the case of the former the result will be an increase in global inequality and vice versa. Recall that the notion of technological dualism (see also Chapter 2) predicts a rise in inequality because countries that are similar to the developed ones will presumably adopt IT at a faster rate than those that are dissimilar. Using a sample of cross-country data I show in Chapter 6 that there is indeed support for this theory. (Note that, unlike Chapter 3, there is no attempt here to adjust for the population size of different countries.)

Another chapter on measurement issues related to the digital divide, Chapter 5 is concerned with the difference between relative and absolute concepts of this phenomenon (the distinction as shown in this chapter is that in the former case IT in developed countries is divided by IT in developing countries, whereas the absolute divide is measured as the stock of IT in developed minus the stock in LDCs). This distinction is important for two related reasons. One of them is that the digital divide is almost always measured in relative terms. The other is that there are numerous reasons to think that an absolute measure better reflects economic welfare (for one thing because it tells us the differential extent to which inhabitants of rich and poor countries actually benefit from mobile phones and the Internet). What then are the results of using absolute rather than relative measures?

At the aggregate level of developing countries as a group, I find that the digital divide is being reduced for both the mobile phone and the Internet (though less so for the latter). In the case of mobile phones there are only a few countries where the digital divide is increasing, whereas for the Internet this occurs with much greater frequency. The difference is, as I see it, due to the greater infrastructural and skills demand of the latter (see Chapter 2). What was common to both forms of IT, however, was the finding that the countries experiencing a widening of the digital divide tended to be drawn more heavily from low-income countries with low diffusion rates. Furthermore, in the case of both technologies the group experiencing a widening of the digital divide tended to show a strong presence of low-income African countries. Here, as in other areas of development policy, countries from this region may suffer from a vicious circle. In particular, at low penetration levels, network effects (whereby a service becomes more valuable as more people acquire it) are low, causing penetration effects to stay low, and so on.

The penultimate chapter in Part I is somewhat more technical than its predecessors: Chapter 7 challenges the (often implicit) prevailing assumption in the digital preparedness literature that variables can be perfectly substituted for one another and can hence be added together. The reality, however, is likely to be nearer the opposite extreme of totally limited substitutability. Beyond a certain point, for example, no extra computers add to output with a given level of skills, infrastructure and so on. (This is one important reason why computers so often go unused in developing countries.) Generalizing this example, I suggest that the components of digital preparedness indicators be multiplied rather than added together. Doing so reveals a substantial understatement of the true difficulty of closing the digital divide and a need for a different set of policies (empirical examples are used to support this view as they are in most chapters of the book). Such policies might include sharing arrangements and the use of intermediaries who come between the technology and those seeking information. (Further analysis of the relationship between the digital divide and digital preparedness is contained in Part II below.)

The final chapter in Part I focuses on and criticizes the popular view that expresses complacency over the closure of the digital divide. One of the key components of this view is an extrapolation of early growth rates of the Internet in developing countries into the future. The problem, however, is that for poor countries beginning the diffusion of the Internet high initial growth rates are almost inevitable. In addition, developed countries are mostly at or near saturation levels so that they are bound to exhibit lower growth rates than in poorer parts of the world. This reasoning suggests that in the future the closure of the digital divide in the Internet will be less rapid than it is now. Furthermore, there is a tendency among the complacency school to redefine the global digital divide in terms of IT per unit of gross domestic product (GDP). This redefinition is important because, if valid, it reduces or even eliminates the existing digital divide since medium- and low-income countries tend to score better on it than countries defined as being relatively high income.

The effect, however, is pure sleight of hand because the measure is then no longer of the digital divide. Rather, it is an input measure where the input (the IT) is divided by the output (GDP). Note that it is even questionable whether the GDP is a true measure of development, for according to Sen’s theory of functionings the ultimate goals are literacy, numeracy, health, etc. A number of factors come between IT an...