eBook - ePub

Models of Futures Markets

Barry Goss, Barry Goss

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 186 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Models of Futures Markets

Barry Goss, Barry Goss

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

This volume presents an entirely new analysis of the economics of futures markets, that will be of interest to both specialists in the area and the generalist economist seeking a new perspective.

Through a combination of theoretical investigation and empirical application, three important themes are explored: the gains from futures trading and the efforts of emerging markets to reap these benefits; rationality and rival hypotheses of trader behaviour, such as noise trading; and the effect of regulatory tools on price formation.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Models of Futures Markets als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Models of Futures Markets von Barry Goss, Barry Goss im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Business & Business generale. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

Welfare, rationality and integrity in futures markets

This volume provides new analysis and evidence on three major themes in the economics of futures markets. The issues selected for discussion are, first, the gains from futures trading and their pursuit in emerging markets; second, rationality and rival hypotheses of agent behaviour; and, third, the integrity of price formation in the presence of regulatory tools. The first and second issues are linked by the hypothesis of utility maximisation, whereas the third issue is related to the other two by the question of whether the price signals to which agents respond are distorted by regulatory intervention. These issues were selected for discussion not only because they are important unsettled questions in the economics of futures markets, but also because it is hoped that the reader will find the individual chapters provide appropriate responses to the specific challenges they address.

The gains from futures trading

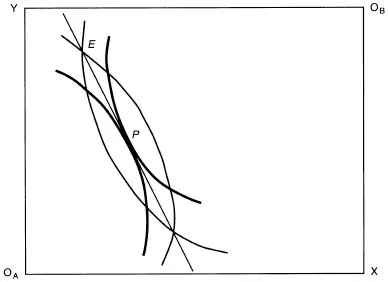

Suppose, in a world with two goods X and Y, in which current consumption decisions are based on currently formed expectations of prices next period, that agent A expects the spot price ratio (Px/Py) to be 2, and agent B expects this price ratio to be 0.5. Suppose further that the current allocation of these goods between A and B, at E in Figure 1.1, is based on these expectations (where Px is the price of X and PY is the price of Y). If a market anticipation of this price ratio in the form of a forward (or futures) price is determined at say 1.25 and if these agents contract at this price, Pareto gains will be made; the allocation will then be at P in Figure 1.1.

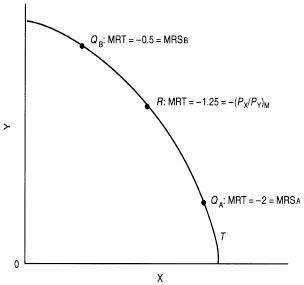

Suppose that A and B are also producers of goods X and Y, and that current production decisions are based on currently formed expectations of prices next period. Assume that with identical product transformation curves T, these agents equate their respective marginal rates of substitution (MRS) to their marginal rates of transformation (MRT) under autarky. Then A will produce at QA and B will produce at QB in Figure 1.2. If the market forward price ratio is established at 1.25 and if both agents adjust to this price ratio, then aggregate production of both X and Y will be increased. Both A and B will relocate their production at R in Figure 1.2. Francis, in Chapter 2, uses these simple but powerful tools to demonstrate the gains from futures trading in what is possibly one of the first general equilibrium analyses of the welfare effects of this institutional arrangement.

Emerging futures markets

Until the early 1970s, the question of the establishment of new futures markets was analysed typically with reference to a list of feasibility conditions which were thought necessary for such markets. This list included the conditions, inter alia, that the commodity in question must be both storable and deliverable (see, for example, Houthakker, 1959, pp. 147–50, 158).2 Such an analysis, however, does not constitute an economic theory and was unable to predict the introduction in 1964 of futures trading in finished live beef cattle, which are virtually non-storable, and in 1982 in share market indices, which are non-storable and non-deliverable.

Figure 1.1 If the initial allocation of X and Y is at E, where E (PX/PY)A = 2 and E (PX/PY)B = 0.5, a futures market is formed in which (PX/PY)M = 1.25. If both agents trade at this price ratio, the allocation is at P, where the slope of the straight line through P is – 1.25.

Figure 1.2 Initially, A locates at QA, where the MRT = MRSA = –2, and B locates at QB, where MRT = MRSB = –0.5. With futures trading, if both agents locate at R, where MRT = –1.25, the production of both X and Y will increase.

By the early 1970s, this commodity characteristics approach had lost favour, and economic theories emerged that focused on key economic variables rather than on attributes of the commodity. Telser and Higinbotham (1977) argued that the net benefits from futures trading are a direct function of price variability, liquidity, turnover and commitments of traders. Empirically, these authors found inter alia that liquidity varies directly with turnover, whereas commission charges and margins vary negatively with turnover. Veljanovski (1986, pp. 25–6) argued that futures markets develop when they are a more efficient vehicle, in terms of transaction costs, than spot or forward markets for transferring certain property rights attached to price. Williams (1986, p. 74), in contrast, argued that futures markets emerge from a need by firms to borrow or lend commodities. For example, a short hedge (purchase of spot, sale of futures) is equivalent to borrowing a commodity and is part of an implicit loan market for the commodity.

Futures trading in emerging market economies is unlikely to have the precedents of a developed cash market and of established forward trading practices, common to futures markets in many developed Western economies, to draw upon.3 Nevertheless, the benefits from futures trading, outlined by Francis in Chapter 2, as well as externalities,4 are available to agents in these economies. Peck, in Chapter 3, discusses developments in two new exchanges in China and Kazakhstan with vastly different prospects: one in Zhengzhou, China, with a major mungbeans contract, has attained substantial volumes and continues to grow; the other, in Almaty, Kazakhstan, with an important wheat contract, is in decline. Peck suggests some reasons for this difference in fortunes between the two exchanges.

Rationality and rival hypotheses

Critics such as Isard (1987) and Meese (1990) have claimed that traditional economic models of exchange rate determination have performed poorly in recent decades, in that they are unable to explain a significant proportion of exchange rate variation and are unable to outperform a naive random walk model in post-sample forecasting. Perceived deficiencies in traditional models to which critics have drawn attention include undue reliance on single equation methods and inadequate modelling of expectations. Alow point was reached, perhaps, a few years later when Krugman (1993, p. 7) claimed that ‘...for the most part international monetary economists have given up, at least for now, on the idea of trying to develop models of the exchange rate that are both theoretically interesting and empirically defensible.’

Prior research, of course, had already cast very serious doubts on the informational efficiency of the foreign exchange market. Although Bilson (1981), Frenkel (1981) and Baillie et al. (1983) did not reject the unbiasedness hypothesis for major currencies with single equation estimation, Bilson (1981) and Bailey et al. (1984) did reject that hypothesis with SURE estimation for a group of major currencies. Hansen and Hodrick (1980) rejected the semistrong efficient markets hypothesis (EMH) for the Deutschmark, Swiss franc and Canadian dollar, against the US dollar, when the set of publicly available information was defined as lagged forecast errors for own and other major currencies. Although Hansen and Hodrick (1980) did not reject the EMH for the British pound/ US dollar exchange rate, Bailey et al. (1984) cast doubt on the rationality of expectations in that market when they found autocorrelated residuals in their single equation estimates.

Unbiasedness embodies the joint hypotheses of rational expectations and risk neutrality, and the predominance of rejections, especially with wider information sets, has been interpreted by some researchers as evidence of market inefficiency (for example, Bilson, 1981; Taylor, 1992) and by others as evidence of a time-varying risk premium (for example, Hodrick and Srivastava, 1984, 1987). (On these various interpretations, the reader is referred to the surveys in Hodrick, 1987; Baillie and McMahon, 1989; Taylor, 1995.)

Although academic research can do little to rectify any lack of speculative efficiency in the foreign exchange market, it can at least address the first set of issues. This is the objective of Goss and Avsar in Chapter 4, who develop a simultaneous model of the US dollar/ Deutschmark market. This model contains behavioural relationships for short hedgers and long hedgers, for short speculators and long speculators, and for agents with unhedged spot market commitments (an alternative way of closing this model is by the introduction of a spot rate equation, as in Goss et al., 1998). Expectations of spot and futures exchange rates are obtained as fitted values on a set of public information defined as all predetermined (current exogenous and lagged endogenous) variables in the model. This method of empirical representation of a rational expectation of an economic variable is based on McCallum (1979), and any test of the rational expectations hypothesis based upon this methodology is a joint test of the expectations hypothesis and the appropriateness of the model (Maddock and Carter, 1982). The post-sample forecasts of the spot rate produced by this model are compared with the forecast provided by a naive random walk model and with that implicit in a lagged futures rate. The first comparison has the clear policy implication that those who would improve economic forecasts of spot exchange rates should take into account information from both spot and futures markets in the context of simultaneous determination because the model presented here by far outperforms a random walk. The second comparison permits a test of the semistrong EMH (Leuthold and Hartmann, 1979). If the model outperforms the lagged futures rate as a predictor of the spot rate, this is evidence against the EMH because the model evidently contains information that is not reflected in the futures rate. This outcome, however, is a necessary but not sufficient condition for rejection of the EMH. The sufficient condition requires a demonstration that the model in question can be used to produce risk-adjusted profits (Rausser and Carter, 1983; Leuthold and Garcia, 1992). However, if the lagged futures price outperforms the model in predicting the spot rate post-sample, this is not necessarily a demonstration of market efficiency, but may be simply a reflection of an inappropriate model.

Noise traders

In the early 1980s, the hypothesis emerged that security prices fluctuated to an extent that was too large to be justified by news on market fundamentals alone. Furthermore, evidence accumulated to support the view that non-information events caused the demand for shares and, hence, their prices to change: for example, it was found that the share market was less volatile on Wednesdays when the exchange was closed, that maximum volatility did not coincide with most important news days, and that shares which were added to the Standard and Poors 500 Index exhibited price increases (Shleifer and Summers, 1990, pp. 19, 22–3).

The noise trader theories of asset pricing, which attempt to explain these outcomes, typically postulate that security prices are determined in a world that comprises rational investors and noise traders (or ‘ordinary investors’). Rational investors fully and efficiently utilise new information and have rational expectations of security prices. Noise traders, on the other hand, respond to non-information, such as the advice of brokers, or they follow fads; alternatively, they may exhibit extrapolative expectations by chasing trends, using technical analysis or ‘stop loss’ orders. Noise traders are assumed, therefore, to misperceive the distribution of security prices. The impact of noise traders on prices will only be significant, of course, if their responses to non-information are correlated.

Although rational investors can make significant returns by arbitrage on the difference between the correct and the misperceived distribution of security prices, such arbitrage is assumed usually to be risky. The result is that the impact of noise traders on p...