![]()

1 Specific Aspects of Childhood Nutrition

Koletzko B, et al. (eds): Pediatric Nutrition in Practice. World Rev Nutr Diet. Basel, Karger, 2015, vol 113, pp 1-5

DOI: 10.1159/000360310

1.1 Child Growth

Kim F. Michaelsen

____________

Key Words

Weight · Height · Body mass index · Obesity · Stunting · Wasting · Growth monitoring · Insulin-like growth factor 1

____________

Key Messages

• Growth is a sensitive marker of health and nutritional status throughout childhood

• Growth monitoring is important both for children with disease conditions and for healthy children

• Early growth is associated with long-term development, health and well-being

• Breastfed infants have a slower growth velocity during infancy, which is likely to have beneficial long-term effects

© 2015 S. Karger AG, Basel

Introduction

Growth is a typical characteristic of childhood; it is also a sensitive indicator of a child's nutritional status. Deviations in growth, especially growth restriction, but also excess fat accumulation typical of obesity, are associated with greater risk of disease both in the short and the long run. Monitoring growth is therefore an important tool for assessing the health and well-being of children, especially in countries with limited access to other diagnostic tools. It is also important in more advanced clinical settings, but is often neglected, favouring more expensive, sophisticated examinations.

Growth of the Healthy Child

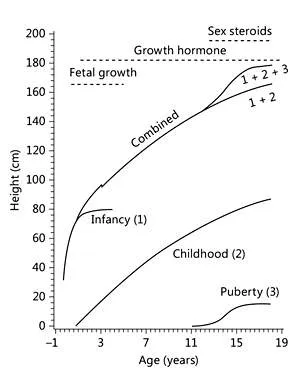

Growth during early life can be divided into periods: intrauterine, infancy, childhood and adolescence. Each period has a characteristic pattern and specific mechanisms that regulate growth (fig. 1) [1]. Nutrition, both in terms of energy and specific essential nutrients, exerts a strong regulatory effect during early life, growth hormone secretion plays a critical role throughout childhood and, finally, growth is modified by sex hormones during puberty.

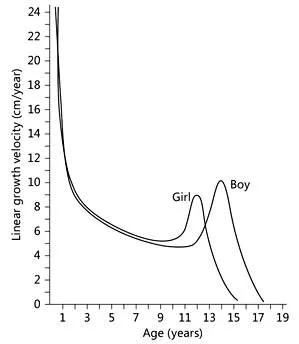

Insulin-like growth factor 1 mediates the effect of growth hormone on growth, but insulin-like growth factor 1 release can also be influenced directly by nutrients. Insulin, which has a potent anabolic effect on fat and lean tissue gain, is also positively associated with childhood growth. Length and weight gain velocity is very high during the first 2 months after birth, with median monthly increments of about 4 cm and 0.9-1.1 kg, respectively. Then, growth velocity declines until the pubertal growth spurt, which is earlier in girls than in boys (fig. 2).

Fig. 1. The infancy-childhood-puberty growth model by Karlberg[1].

Fig. 2. Linear growth velocity according to age in girls and boys. Modified after Tanner et al. [11, 12].

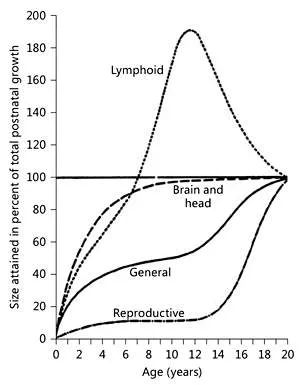

Fig. 3. Relative growth of different organ systems. From Tanner [13], with permission.

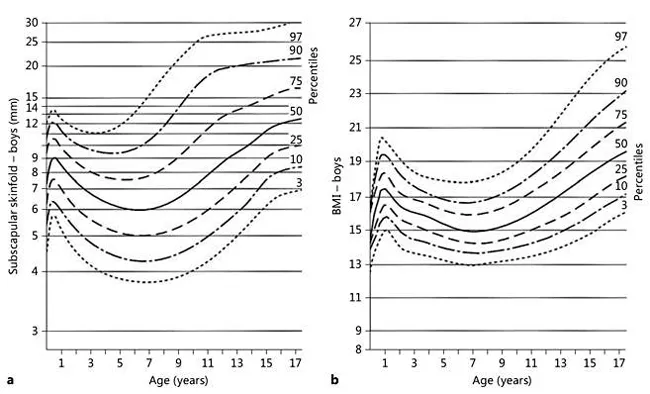

Different organs grow at very various rates (fig. 3). The relative weight of lymphoid tissue is greater in children than in adults and the size of the thymus peaks by 4-6 months of age and then decreases [2]. The brain, and thereby head circumference, grows mainly during the first 2 years of life, with the head circumference reaching about 80% of the adult values by 2 years. Body fat mass, expressed as percent total body mass, increases from birth to the age of about 6-9 months, then decreases until the age of about 5-6 years, followed by an increase (so-called ‘adiposity rebound’). These changes are reflected in reference curves for both BMI and skinfolds (fig. 4). The adiposity rebound typically occurs by 5-6 years of age. If this happens earlier, the risk of developing obesity is increased [3].

Fig. 4. Reference charts (percentiles) for subscapular skinfold (boy) and BMI. Modified after Tanner and Whitehouse [14] and Nysom et al. [15].

Regulation of Growth

Many factors influence growth. Genetic influences are strong, but these can be modified by multiple environmental factors. Ethnic differences are likely to be caused more by the environment than by genetic factors. The new WHO growth standards obtained for 0- to 5-year-old children from different parts of the world show a similar growth potential. Basically, under optimal nutritional and socioeconomic conditions, the growth pattern was the same, independent of geographic and ethnic diversity (see Chapter 4.1). Other studies show that with children of families moving to a country with very different dietary and socioeconomic conditions, the growth pattern can change over time (secular trend); within one generation the growth pattern becomes more like that in the adopted country. Adult height has increased over the last decades in many populations. This secular change came to a halt in Northern Europe around the mid-1980s, while it continues to increase in other countries [4]. The age of puberty differs considerably between populations, with later onset of puberty in populations with poor nutritional status.

Nutrition has a central influence on growth, especially during the first years of life. Breastfed infants grow faster in their first months and are slightly shorter at 12 months of age, they weigh less and are leaner than formula-fed infants [5]. Breastfeeding also influences body composition. Breastfed infants gain more fat during the first 6 months and gain more lean mass from 6 to 12 months of age than formula-fed infants [6]. The growth pattern of breastfed infants is likely to play a role in the effects of breastfeeding on long-term health. Differences in protein intake (quality and quantity) between breast- and formula-fed infants are likely responsible for some of the differences in growth pattern between breastfed and formula-fed infants. This is in line with evidence suggesting that cow's milk promotes linear growth, even in well-nourished populations [7]. There is some evidence suggesting that high protein intake during the first years of life is associated with an increased risk of developing overweight and obesity later in life [8, 9]. Other aspects of nutrition are also important in development of overweight and obesity, as discussed in Chapter 3.5.

Nutritional Problems Affecting Growth

Globally, the most common cause of growth failure is inadequate dietary quality and, in some cases, insufficient energy intake. Growth-related nutrients, e.g. zinc, magnesium, phosphorus and essential amino acids, are important. Overall, protein deficiency is seldom a problem, but if the protein quality is low (typically in diets based on cereals or tubers), essential amino acids such as lysine may be low in the diet, and this can have a negative effect on growth. Undernutrition, i.e. low weight-for-age, can be caused by low height-forage (stunting), low weight-for-height (wasting or thinness) or a combination. In populations with poor nutrition, stunting is regarded as a result of chronic malnutrition and wasting a result of acute malnutrition. However, both forms can coexist in a given individual; thus this nomenclature is often an oversimplification. Many acute and chronic...