![]()

Sadness, grief, guilt and isolation are feelings parents described when they were told their child was “mentally retarded.” The strange names for the diagnosis—mongolism, infantile schizophrenia, brain damage, spastic—were unknown to them. They turned to their doctors, pediatricians, and religious leaders for help only to learn that they too knew very little. Information was scant, contradictory, and often inaccurate. Based on “disreputable” research, mothers were often blamed for their child’s “condition.” The “prescription” most parents were given was to institutionalize. To forget about this child and have another.

Parents describe how dependent they were on the medical system for guidance. After nearly twenty years of hardship during the Depression and World War II many Americans learned to depend upon “official leadership” and agency programs for relief. Yet when they sought an institution for their child, they found that lack of funds and staffing during the Depression and war years left them overcrowded, understaffed, and with inhumane conditions. During the economic optimism of cold war America, to put one’s child on a waiting list for the purgatory of institutional life, as it was often described, added another layer of stress, guilt, and anger. The relationship of the parent to the institution is the first chapter in this story and the first step toward civil activism for many.

“About Children” follows five families whose range of experiences gives a picture of the ways parents pulled inward, made choices, and grappled with issues in the home and community. While many kept their child at home, others chose an institution or special boarding school, though without abandoning their child. These parents stayed close to their child, visiting often and providing an ever-watch-ful eye. Their presence helped to transform institutional conditions.

Marcella Nelson and her daughters Linda Nelson and Nina Seaberg talk about Merrill

The Nelsons

Marcella: Merrill was perfectly normal when he was born. When he was two days old, he got a high temperature and jaundice. It was the high temperature that caused the brain damage. It was 1936 and they didn’t know how to treat him. The doctor just told me to bring him home and love him. At first, it was hard for me to realize that something was wrong. It was my husband’s mother who made me face it. He was a good baby, but he was slower than my daughters. Then we found Dr. Wyckoff. They really didn’t have any treatment; they called it spastic at that time. He invited Dr. Earl Carlson from New York, who had cerebral palsy, to meet with some of the doctors and parents and explain certain things to us, to make us aware of what we had to face. One doctor said, “There is nothing out there for your kids. If you want something to happen, you’re going to have to do it for yourself.” Another doctor suggested massage and to give him experiences. They said not to spoil him, he has enough problems. He was quite pysically disabled, and they said he wouldn’t walk. But he did when he was ten.

Dr. Wyckoff was an orthopedic surgeon, and, unlike the other doctors, he got us to try and think of what we could do. A small group of us whose children were patients of his interviewed other doctors and got the names of their patients who had cerebral palsy. We were to find others and share what we knew. Some mothers were scared, some weren’t, some were eager, others kind of held back, some were embarassed and ashamed. We were the mothers and others.

I guess I had to have a reason to be an activist.

Children from the spastic children’s school, c.1945, unknown location

We parents became really obnoxious after awhile. There was no special education at that time, and the public schools wouldn’t take our kids because they thought they weren’t educable. So in 1942, our church let us use their Sunday school rooms during the week. There were only six or eight children to start. There was a steep flight of stairs. I’ll never forget those Far West Cab drivers who would come and help us carry our kids up those steps. I remember some of the mothers bringing their kids on the streetcar. So often they arrived late, or not at all. Miss Boxeth and her sister came to teach. They were older, but they taught speech and anything they could. Two old retired teachers—we convinced the school board to give us the teachers and pay their salaries. We had to cook for the school and clean. We charged $20, but we never turned anyone away. We had to prove that these children could learn. The teacher reported to the school board and we kept pressuring. I went to women’s guilds to speak and Dad went to talk to legislators in Olympia. In 1944, there were so many parents blowing their horns they gave us a portable unit behind an elementary school on Warren Avenue and we became a part of the Seattle Public Schools.

Nina: My mother forgets. But I remember how upset she got when people called and said we have a neighbor with a child, we think it’s in the back room, we’ve never seen it. Maybe this is someone you should contact, and of course, she would. Because of Merrill there were a lot of things we didn’t do. But it was also World War II with gas rationing, and all kinds of things you couldn’t do. But this was my family—it made no difference. Merrill was my brother. I don’t think we were really aware that we were doing anything different. But we were the only kids who went to kindergarten with housemaid knees from scrubbing floors at home. But I thought this is just what happened.

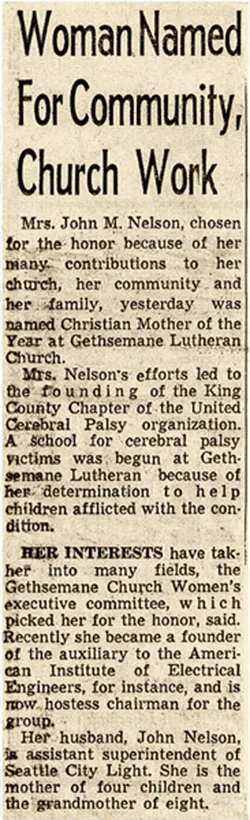

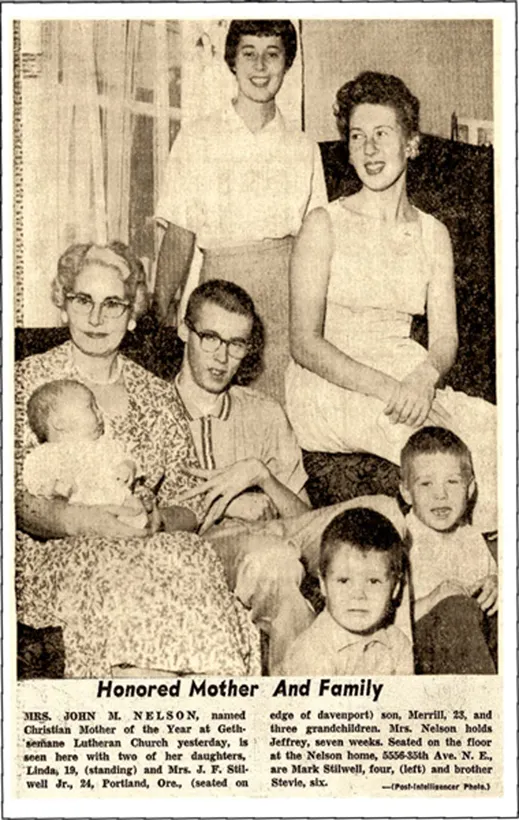

Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 8,1960, p. 7

It’s funny, I’ve always got the feeling that people would say when they saw me, There goes Marcella, all she talks about is …

United Cerebral Palsy sheltered workshop, 1959

Linda: Merrill took a lot of Mom and Dad’s time away from the family. As the youngest I’m aware that my sisters took care of me a lot. My mom and dad were always working on things. After Merrill graduated they hit the pavement and got a sheltered workshop started. After all the work getting him into school, they didn’t want him home with nothing to do.

I think we were well accepted in our neighborhood. I do remember discrimination—going to restaurants where I was asked not to bring my brother back. There was always pain outside of our immediate circle of people.

Nina: One incident I will always remember is one day when we went with mother to a deli downtown. There was a man ahead of us in line—and mother said he was spastic. He couldn’t talk very clearly and the waitress skipped over him. My mother said to her, “Don’t take my order, this man was first!” We were young and shocked at her anger.

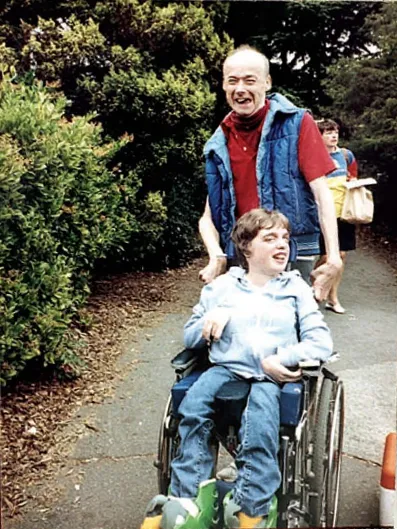

Linda: They always said Merrill wouldn’t do a lot of things, but he did. He tried to talk, but you couldn’t understand him. He would spell on the palm of your hand. He wrote notes and he used the typewriter. He was also an artist and did many paintings, and he read. When he got older he got angry because the story he wanted for his life and the story he was forced to have were very different ones. Mom and Dad made a point to give him as normal a social life as possible because this was a time when kids like Merrill would have been put in an institution—parents who had a child like Merrill would have been asked to sterilize him. Eugenics was popular at the time. We weren’t just a family, we were a family with a disability; it defined our history, it defined our story. Merrill was my brother.

Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 8,1960, p. 7

Marcella: When Merrill stood straight he was six feet tall. The opinion was that he had a high IQ. He read but I’m not sure how much he really understood. He was interested in his father’s job with Seattle City Light. Our concern was that we would have to live forever—to outlive Merrill. Some of the parents started to die so we worked to get a residential home built. He met his girlfriend, Cynthia Fischer, there and he would have liked to been married, but he died before that ever played itself out. He died in 1991 from the same thing that caused his condition. He had surgery for his neck and they gave him a procedure to see if he could swallow. Well fluid got into his lungs and he died.

The Dolans

Katie: Patrick was born in 1950. He was my first child. The family literally worshiped this child. With autism you don’t notice anything. Often they are beautiful children. He talked before he was a year old—all kinds of words. We thought he was so advanced. He didn’t crawl; he walked and ran and climbed. He was three when he was diagnosed as infantile schizophrenic. Without any real tests or proof, they jumped to the conclusion it was the mother that caused it. We believed it. We grew up with the belief in God, Jesus, and the doctor—rolled into one. I mean if they told us to cut off Patrick’s head and adjust a few things and sew it back on we would have let them. So I went into psychotherapy. I suppose it helped me. But it didn’t help Patrick. He had stopped eating and talking. He’d walk up the stairway and throw...