![]()

PART ONE

History of Shiraz from Its Founding to the Conquest of Timur

![]()

1

History of Shiraz to the Mongol Conquest

I said, turn your path to the greater world,

So I should be free of the chains of slavery.

But I found no place for me outside of Fars,

Not Syria, not Anatolia, not Basra, and not Baghdad.

—Hafez

ORIGINS

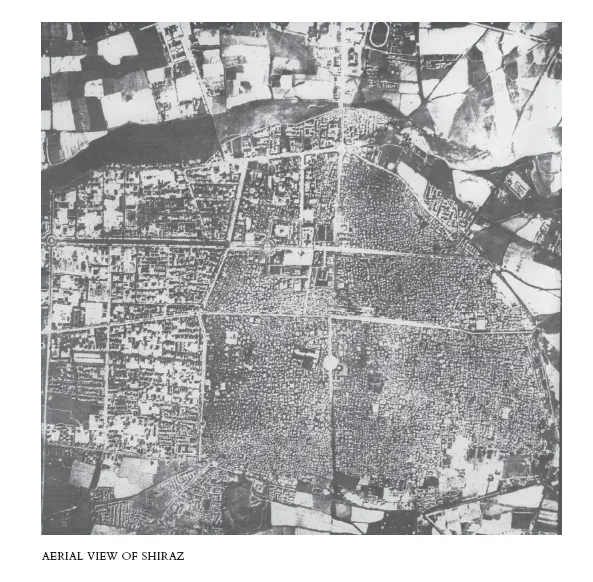

Shiraz is the capital of the Iranian province of Fars, the ancient homeland of the Achemenian (ca. 549-330 B.C.E.) and the Sassanian (ca. 224-651 C.E.) dynasties. The Greeks called this area Persis, from which came our name “Persia” for the entire country. The Iranians derive the name of their beloved national language, Farsi, from the name of this province.

Fars is unique among Iranian provinces in its geography. It consists of a series of plains or valleys (jolgeh, dasht) at varying elevations separated from each other by mountain ranges. Each plain, depending on its latitude and elevation, has a distinct climate, and these climates have determined three distinct types of agriculture. The high elevations, or sardsir, produce grain, apples, walnuts, mulberries, etc.; the lowlands, or garmsir (collective, garmsirat), produce dates and citrus; and the temperate or mo'tadel regions produce grain, pomegranates, grapes, and sour oranges.1 The most famous pre-Islamic Iranian dynasties originated and built their great monuments in these plains—the Achemenians first in the Dasht-e-Mashhad-e-Morghab in the highlands northeast of Shiraz and later in the more temperate plain at Marvdasht; the Sassanians in the subtropical valleys of Darab, Firuzabad, and Kazeron.

Shiraz today sits about 5,500 feet above sea level, in an area of mild climate at the northwestern end of one of those long, narrow plains, which runs northwest to southeast. It has occupied the same site for 1,300 years. The medieval city, although much changed by reconstruction and Pahlaviera town planning, is located in the eastern and southern parts of the modern town.

Shiraz was not always the capital of Fars, and by Iranian standards it is a new town. Muslim historians agree that the Omayyad Caliph Abd al-Malek b. Marwan founded it in the first/seventh century. A local historian tells us, “It has never been defiled by idol-worship.”2 Another historian, Hamdullah Mostowfi of Qazvin, relates several accounts of the city's origin and concludes:

The most reliable account, however, is that after the preaching of Islam, Shiraz was founded, or restored, by Mohammad, brother of Hajjaj b. Yusef Thaqafi [Omayyad governor of Iraq]—another version giving it as restored by his cousin Muhammad b. Qasem b. Abi Aqil—the date of its restoration being 74/693.3

Pre-Islamic settlement must have existed at or near Shiraz, if only to give the new city its name—notice Mostowfi's use of the word “restored.” The anonymous geographer of the Hodud al-Alam (tenth century C.E.) reports the existence in Shiraz of two venerated fire temples and an ancient fortress, called Shahmobad.4 Pre-Islamic remains on the Shiraz plain also indicate the existence of settlement near the site of the present city. There are Sassanian reliefs both east and northwest of Shiraz at Barm-e-Delak and Guyom, respectively, and remains of Sassanian castles at Qasr-e-Abu Nasr, east of the city, and at Qal'eh-ye-Bandar (Fahandezh) near the present Sa'adi village. The latter has been tentatively identified as the geographer's Shahmobad fortress.5

Elamite clay tablets from Persepolis contain the name of the castle of Tirazzish, in one version in the form Shirrazish. On late Sassanian and early Islamic clay sealings found at Qasr-e-Abu Nasr appears the name Shiraz, along with Ardashir Khurreh, the Sassanian administrative unit with its capital at Firuzabad, of which this pre-Islamic Shiraz was a part. This evidence suggests that the name Shiraz originated from the Tirrazish (or Shirrazish) of the Elamite tablets and that the name originally applied to a fortress on the site of Qasr-e-Abu Nasr. This settlement, which flourished in the sixth, seventh, and eighth centuries C.E., must have been the center of government for the Shiraz plain until the founding of the present day city, to which it gave its name.

During the years 640-53, Muslim armies, in a series of expeditions from Basra in southern Iraq, conquered the Sassanian province of Fars, which in its five districts included present-day Fars, Yazd, the Persian Gulf coast and islands, and parts of Khuzestan.6 The Muslims reached the Shiraz area in 641. There was no city in that region, but there were castles, which agreed to pay tribute to the conquerors. The Sassanian capital of Fars, Estakhr, did not finally submit to Arab rule until 653 following a bloody revolt. During the fighting at Estakhr, the Arabs reportedly used the plain of Shiraz as a camping ground for their army.

SHIRAZ UNDER THE ARAB CALIPHS

The chief town of Fars, Estakhr, had close connections with the Sassanian dynasty and the Zoroastrian faith, and the new Arab rulers wanted to create a rival, Islamic center in their newly conquered territory. When the Arabs originally founded Shiraz, it was laid out to be greater than Esfahan, and to be a thousand paces larger. Despite this auspicious beginning, Shiraz remained a provincial backwater for the first two centuries of its history, overshadowed by its older rival, Estakhr. Estakhr would keep its importance as long as there was a substantial Zoroastrian community in Fars, which would prefer not to live in the new, Muslim Shiraz.

The historian Richard Frye believes that the final decay of Estakhr and the growth of Shiraz coincided with the decay of Zoroastrianism and large-scale conversion to Islam in Fars.7 The sources say little of this early period, and the city did not have a jame’ (congregational) mosque until the late ninth century, when the Saffarid rulers established Shiraz as the capital of their semi-independent state.

During this earliest, obscure period of Shiraz's history, important events were shaping the city's future appearance, geography, and social and religious life. By tradition, during the rule of the Abbasid Caliph Ma'mun (813-833), Abbasid authorities in Shiraz executed several descendents of the Caliph Ali. The martyrs’ tombs—often rediscovered after centuries of oblivion—were to become major centers of Shirazi pilgrimage, burial, scholarship, and charity. According to later (Sunni) tradition, in the disturbances following the accession of the Caliph Ma'mun in 813 and the death of the eighth Imam of the Shia, Reza b. Musa Kazem, in 817, three of the Imam's sixteen brothers took refuge in separate houses in Shiraz. According to varying reports, there they either lived in obscurity and died natural deaths, or were executed by the Abbasid governor of Fars.

Shiraz's original group of patron saints was complete when the nephew of these three brothers, Ali b. Hamzeh b. Musa Kazem, fled to Shiraz around 835. There he took refuge in a cave with a few friends and made his living gathering and selling firewood. After a short time Abbasid agents discovered and executed him.

Four centuries passed before thirteenth-century Salghurid rulers and their ministers discovered most of these lost or forgotten graves and endowed them with appropriate monuments. If the original graves do, in fact, antedate the building of the first congregational mosque in Shiraz (894), then their locations, and the sites of other identified early graves, provide an outline of some important points in or near the ancient city. These points were to become centers of the city's religious and economic life.

The location and identification of these graves comes from tradition rather than solid historical evidence, but these traditions are almost the only surviving guide to the earliest period of the city's history. Ali b. Hamzeh's grave was never lost, but over a century passed before Fana Khosrow Azod al-Dowleh, the Shia Deilamite ruler of Shiraz between 950 and 983, restored the grave and improved the site. In the case of Sibawayh the Grammarian (d. 796), the sources are nearly unanimous in locating his grave in the Bahaliyeh district of Shiraz.

The rediscovery of the reputed graves of the three brothers of the eighth Imam, however, had to wait more than four hundred years. According to local tradition, the Amir Moqarreb al-Din Mas'ud, the famous minister of the Salghurid Atabek Abu Bakr b. Sa'd (1226-60), found the grave of Ahmad b. Musa (now famous as Shah-e-Cheragh) while having land cleared for a building near the old congregational mosque. The authorities identified the saint by a seal ring on his miraculously intact body. In the same period, after people saw light emanating from a hill, came discovery of the site presently called Astaneh, the purported grave of Ahmad's brother Hosein. The owner of the property, Atabek Abu Bakr, had the hill excavated and discovered an intact body with a Qoran in one hand and a sword in the other. When the body had been identified (by its “splendor”), the ruler ordered a dome built on the site.8

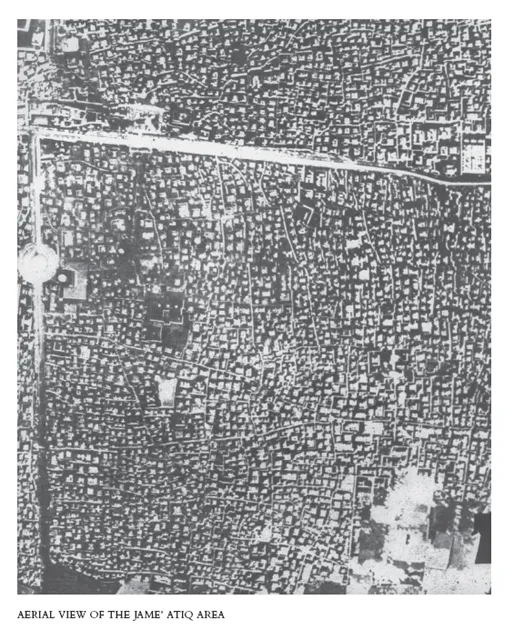

Shiraz acquired its congregational mosque in 894, when Amru Leith the Saffarid ordered the construction of the Masjed-Jame (now known as the Jame Atiq, or Old Congregational Mosque). He chose a central location near the bazaar of Shiraz, and later historians report that the Bazar-e-Bozorg (Grand Bazaar) ran to the door of this mosque.9

SHIRAZ UNDER THE BUYIDS

Under Buyid rule in the tenth century C.E., Shiraz grew into a large and prosperous town. It was both the capital and largest city of Fars province (including Yazd), followed in importance by Fasa and the port of Siraf. It was a league in circumference and remained without a wall until 1044. Economically, it was of considerable importance, and then, as now, consumed the products of its province rather than raising produce for export. Among the products of Fars noted in the tenth century C.E. were grapes, textiles of linen, wool, and cotton, collyrium, rose water, violet water, palmblossom water, carpets, and the woven rugs called zilu and gelim.

The city itself had twelve quarters (called tassuj) and eight gates.10 In 974 Fana Khosrow Azod al-Dowleh Deilami, the greatest ruler of this dynasty, built a suburb for his court and his army south of the city. He named it Fana Khosrow Gerd (gerd = town or fortress) after himself, and during his reign it became so prosperous that its taxes amounted to 20,000 dinars. But a few years after Azod al-Dowleh's death the Buyids abandoned his city and its palaces, and looted its materials to build fortifications. By the beginning of the twelfth century, as part of the general decline and insecurity, the site had reverted to farms, with a tax value of only 250 dinars.

More substantial Buyid remains still exist in and near Shiraz. There is the original shrine of Ali b. Hamzeh, located just north of the Esfahan Gate. Farther away are the Gonbad-e-Azodiyeh (Azod al-Din's Tower) on the mountains north of the city, and the Band-e-Amir, a dam on the Kur River twenty-five miles to the northeast. Also surviving is Ab-e-Rokni, an underground channel (qanat) named after Rokn al-Dowleh Hasan b. Buyeh, the father of Azod al-Dowleh. This channel supplies water to Shiraz from a source nine miles northeast. Long vanished are the Azodiyeh Library and Azodiyeh Hospital (Dar al-Shafa), although the name of the latter has survived as a quarter of the old city.

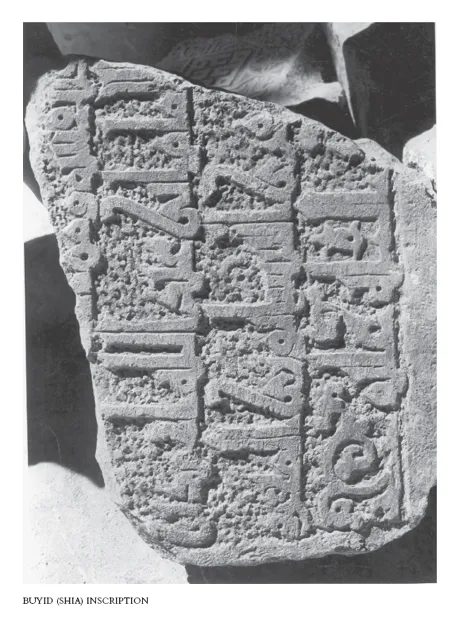

There are also inscriptions, believed to date from Buyid times, located around the city. The most interesting one (p. 10) is the gravestone of Ahmad b. Ali Bishapuri (or Nishapuri). Originally buried near Ali b. Hamzeh, his gravestone was moved to the garden of Haft-tan on the northern edge of the city during rebuilding of the shrine about 1950. Mr. N. H. Pirnia, who helped me read the inscription, believes that this Ahmad b. Ali had a Zoroastrian ancestor named Shadhfari, and that he was a Shia, because of the final inscribed “Ali” and the following decorative doubled vav, representing Shia twelve in abjad numerology.11 Other surviving Buyid inscriptions are an inscribed mehrab (prayer niche) in the hills north of Shiraz, the grave of Abi Zare’ Ardebili, and the grave of Sheikh Abu Sa'eb Shami (d. 957), who was famous for owning a hair of the prophet. His grave was popularly called Mu-ye-Rasul (the prophet's hair) or Asar-e-Rasul (the prophet's relic).12

Members of the Buyid family were followers of “twelver” Shi'ism, and as such actively encouraged the preaching of this religion by instituting public mourning during Moharram, celebrations of Eid-e-Ghadir, and cursing the enemies of the family of the prophet. But the Buyids, and Azod al-Dowleh in particular, were generally tolerant rulers. They paid the greatest respect to the famous Sunni saint and mystic of Shiraz, Abdullah b. Khafif Sheikh-e-Kabir (882-982). Azod al-Dowleh's son, Sharaf al-Dowleh Shirzil (r.983-89) built a khaneqah (dervish lodge) for the sheikh's followers outside the city gates.

In Buyid times, Fars was famous for having the largest Zoroastrian population of any Moslem province—every region possessed a fire temple. The non-Moslems of Shiraz wore no special mark to distinguish themselves, and the bazaars of the town were illuminated during Iranian festivals such as Mehregan and ...