![]()

1

SCIENCE AND THE CREATION OF THE JAPANESE WOLF

On a warm, Rocky Mountain morning, while in my office preparing to teach a summer class, I received a letter from Inoue Katsuo, one of my teachers and a professor of Japanese history at Hokkaido University in Sapporo. I put down my lecture notes and eagerly ripped opened the envelope. Along with several prominent articles Inoue had recently published, I discovered a newspaper clipping from the Asahi shinbun (Asahi newspaper) that featured a color picture of some sort of wild dog. “I thought you might be interested in this,” he wrote. As I read the article, I began to realize that when I had ripped open this letter I had opened a metaphoric Pandora's Box, one that would force me to explore the taxonomy of Japan's wolves and, more generally, the cognitive and cultural origins of Japan's natural history.

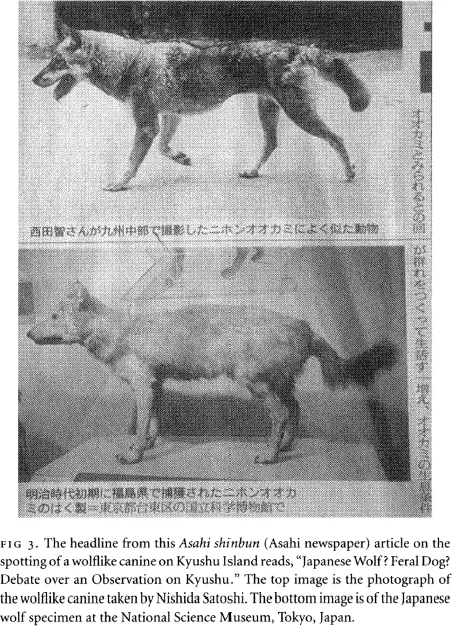

I learned that on the evening of July 8, 2000, Nishida Satoshi, a high school principal from Kitakyūshū City, in Fukuoka Prefecture, had photographed the medium-sized canine with its tongue hanging from its mouth as it loped within about ten or fifteen feet of him. The photograph, although only of grainy newspaper quality, shows that the canine was mostly gray and black, but that it also had shades of orange on its legs and behind its ears (see fig. 3). As it turns out, Nishida was an animal enthusiast, and he explained to Asahi reporters that the wild dog had approached him while he was hiking and then it had just vanished into the mountains. The animal was, quite literally, some sort of mountain dog. Later, the photograph was shown to Imaizumi Yoshinori, former zoologist at the National Science Museum in Tokyo (Kokuritsu Kagaku Hakubutsukan), who said that the animal resembled the extinct Japanese wolf. Needless to say, with the apparent sighting of an animal that now inhabits only the Environmental Ministry's “extinct species” list, the incident caused quite a stir in Japan, and over the next several weeks the photograph was plastered over most major dailies. Controversy surrounded the photograph, however. Maruyama Naoki, of the Tokyo College of Agriculture and Industry (Tōkyō Nōkō Daigaku), questioned Imaizumi's suggestion that the animal was actually a wolf. Currently head of the Japan Wolf Association and spearheading an effort to reintroduce wolves to that country, Maruyama explained that, during his studies of Mongolian wolves, even to get within a quarter mile of one was extremely rare, and so he doubted that Nishida could get so close.1

In the interview with Asahi reporters, Maruyama questioned the existence of wolves in Japan for ecological reasons as well. He explained that a mating pair of wolves can have seven to eight pups per year, and that this family becomes the core of what later develops into a pack. Maruyama thought it unlikely that a lone wolf would be spotted. The dynamics of wolf reproduction, combined with activities in Japan that have caused an explosion of deer numbers, led Maruyama to speculate that if Japanese wolves still existed, there would be significantly more sightings. He added that even more reports could be expected of their distant howls in the mountains. Maruyama admitted that the animal in Nishida's photograph shared some characteristics with the Japanese wolf, but to him, it appeared to be a German shepherd hybrid of some kind. The article went on to explain that Aimi Mitsuru, of Kyoto University's Primate Research Center (Reichōrui Kenkyūjo), had some time ago contacted Leiden (where one of the best-known specimens of the Japanese wolf remains housed) and elsewhere about obtaining samples for DNA testing; such samples might be compared with samples of hair miraculously recovered near Kitakyūshū City. These attempts to obtain DNA from preserved specimens had failed, however, because the harsh chemicals used in the taxidermy process ruined the samples. Even with quality samples, distinguishing dogs from wolves with mitochondrial DNA proves complicated because wolves and dogs became distinct species only about 15,000 years ago.2 More recently, scraps of dried flesh recovered from a wolf skull discovered in a private home in Kōchi Prefecture, on Shikoku Island, yielded inconclusive results; though wolf DNA to be sure, it nonetheless differed from more-common Eurasian wolves.3 Basically, the newest marvel of modern taxonomy, mitochondrial DNA testing, failed to distinguish between wolves and dogs with the Kitakyūshū, Leiden, and Kōchi specimens.4

One possible genetic reason for the inability of DNA testing to make definitive distinctions between Japanese dogs and wolves might be that Asian spitz-type breeds (which include Japanese breeds such as the Shiba and Akita) are now understood to be the closest genetic relatives to wolves and to the earliest “pariah dogs,” the latter of which originated in Asia and migrated alongside nomadic peoples around the globe. Quite simply, not only do Japanese breeds phenotypically resemble wolves, but they also genetically resemble wolves and these early nomadic pariah dogs. As Heidi Parker and her colleagues have noted, this makes genetic testing unusually complicated, particularly if any hybridization between the species occurred in earlier times.

As I stuffed Inoue's letter back in its envelope, I thought that where DNA testing has failed, surely a historical inquiry could solve this vexing mystery of the taxonomic status of Japan's wolves. Even with available sources, however, making any taxonomic determination is complicated because the zoological category of wolf in Japan is a surprisingly recent historical construct, one that did not really solidify in the minds of scientists until the beginning of the twentieth century. The emergence of Nihon ōkami, or the Japanese wolf, became possible only with the emergence of many other distinctly “Japanese” things at the turn of the century, such as Japan's unique brand of ethnic nationalism and its imperial ideology.5 Prior to the early twentieth century, the categories of canine remained diverse and dependent on social situations and ecological contexts; wolves (ōkami), sick wolves (byōrō), mountain dogs (yamainu), honorable dogs (oinu), big dogs (ōinu), wild dogs (yaken), bad dogs (akuken), village dogs (sato inu), domesticated dogs (kai inu), and hunting dogs (kari inu) all loped across the boundaries of status and of occupational, religious, and regional understandings of the categories of canine. Only in the early twentieth century, after debates spawned by the introduction of the Linnaean system and after changes brought by the Meiji Restoration, did the stable category of Japanese wolf emerge in the context of the development of Japan's modern national identity. It is this modern Japanese wolf—a product of the twin historical forces of the birth of the modern Japanese nation and the development of its own zoological sciences—that this book explores.

The introduction of the Linnaean system to Japan in the 1820s reconfigured botanical and zoological taxonomies, and so, for this chapter, the Linnaean moment serves as the epicenter of several enduring controversies over Japan's wolves, controversies resurrected by the sighting near Kitakyūshū City. Of course, these controversies tell us something valuable about the way the natural world was classified prior to Japan's Linnaean moment, when the joint legacies of imported Neo-Confucian and, simultaneously, more native Japanese orders ruled discussions regarding the classification of wolves and other animals. But they also tell us something about how the scientific categories inherent in the supposedly “universal” Linnaean system often proved counterintuitive to earlier, more ecologically and regionally valid methods of classifying the natural world.6

Scott Atran, an anthropologist of science, has argued that the Linnaean system was actually “universal” in a cognitive sense because it was rooted in earlier folk-biological “life-form” and “generic-specieme” categories shared by most human societies, but ones that Carolus Linnaeus, in the eighteenth century, converted into scientific categories of “species” based on morphotypes and the “rational intuition” of science. Atran insists that with human beings, “there are not any intrinsic differences in our cognitive dispositions to classify natural” objects, and Linnaean categories originated from this basic human cognition. That they made sense naturally to early modern Japanese scientists is one reason Linnaean taxonomies so easily transferred and translated into the Japanese context. For Atran, the similarities between European and East Asian folk-biological taxonomies are the result of “a biological conception of the world common to folk everywhere,” and this sort of propensity for rational thinking and even science, whether in Europe or in East Asia, “marks the true bounds of our common vision of the world” as humans.7

In Japan, with the rise of Western learning, European classifying systems piqued the cognitive interests of many Japanese natural scientists, who, by the first half of the nineteenth century, began uprooting plants from the pots of earlier Neo-Confucian and Japanese taxonomies and planting them in the Western scientific ones introduced by Dutch traders and their German doctors. In this way, the “universal” qualities of the Linnaean system were important in another sense, one less biological than cultural. Like Japan's adoption of the Gregorian calendar and acceptance of world time in the latter half of the nineteenth century, the Linnaean system classified the plant and animal life of Japan according to the same symbolic logic as that used by the Western powers. One suspects that, with the adoption of the Linnaean system, Japan took the first step, in the arena of science, in placing itself on a cultural and cognitive parity with the countries of Europe and the United States.

No matter how progressive this enterprise was to Japan's nineteenth-century modernizes, however, the hasty application of the Linnaean system still failed to address critical taxonomic issues regarding Japan's wolves. This failure opened the door for continued questions (many raised by postwar scholars who harkened back to Japan's pre-Linnaean past) over whether Japan's wolves were really, according to the universally accepted Linnaean system or otherwise, wolves at all. This is one reason the Kitakyūshū City sighting had caused such a stir in Japan's newspapers.

JAPAN'S PRE-LINNAEAN WOLF TAXONOMIES

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Japan's natural scientists were scholars for whom the semantics of Chinese cosmology, the nomenclature of natural order, the principle inherent in all things, the folklore of the fantastic, not to mention the authenticity of the historical, figured prominently in their categorical logic. Strict morphologies, internal anatomies, the reproductive “seeds” of natural creatures, and other aspects of the “rational intuition” inherent in Linnaean science were far from the minds of these scholars. Of course, they actively ordered their world in a biological and cosmological sense, but they did so with, to use Michel Foucault's words, the “grid created by . . . a language,” in their case the elite East Asian written language of Chinese ideographs and pictographs (called kanji in Japanese), and with the precedent set by that language in the canons of Neo-Confucian encyclopedic writings from China.8 Confucius had taught that language provided order in the form of the “rectification of names” (Chinese chengming, Japanese shōmei). As he explained in the Lunyu (Analects), “when the gentleman names something, the name is sure to be usable in speech, and when he says something this is sure to be practicable. The thing about the gentleman is that he is anything but casual where speech is concerned.”9 The learned gentleman strove for order through “speech”—the accurate use of names and language—and so too did early Japanese natural scientists.

Later, because Neo-Confucianism became essentially state supported and intellectually embedded in early modern Japan's educational and scientific landscape, natural scientists emphasized the study of past writings, mostly by certain Chinese and, to a lesser extent, Japanese scholars, and participated in only a limited amount of biological discovery until the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. One historian summed up this climate when he wrote: “Tokugawa Confucianism was not a progressive branch of study, constantly pushing at the frontiers of new knowledge. All that was worth inventing had been invented by the Sage Emperor; all that was worth knowing had been known by Confucius. The task of later generations was simply to absorb this body of knowledge passively and with humility.”10

For the Chinese scholar Zhu Xi, whom historians credit with synthesizing Confucian humanism with Buddhist and Taoist creeds in the twelfth century to form Neo-Confucianism, this “body of knowledge” and the study of nature did reveal an order, just not the scientific order and natural history advocated by Linnaean taxonomists. Rather, Zhu Xi, much like Confucian scholars before and after him, believed that the “investigation of things” (kakubutsu in Japanese), including things in the biological world, exposed the inherent principles of a universal moral, order that mirrored and, subsequently, legitimized human social and political hierarchies. Indeed, the study of nature only affirmed the natural place of people within their setting. As Zhu Xi wrote, if scholars “investigate moral principle, everything will naturally fall into place and interconnect with everything else; each thing will have its order. . . . In learning, you should desire nothing more than to understand this moral principle.”11 Most early modern biologists followed this sage advice and investigated the natural world to better understand the relationship between humanity, nature, and social virtue. For this reason, those who became interested in the natural sciences were often part of a broader category of scholars who studied traditional Chinese medicine (kanpō) or, later, Dutch medicine, perhaps the two most respected arenas of scientific inquiry in preindustrial Japan because they produced the most social good. Many of the early modern natural scientists discussed in this book, such as Noro Genjō, Ono Ranzan, and Itō Keisuke, came from such medical backgrounds.12

Though sophisticated, the taxonomies constructed by Japan's seventeenth- and eighteenth-century natural scientists remained, at least according to Scott Atran's framework, folk-biological in nature for three reasons. First, early modern Japanese taxonomies “represent a holistic appreciation of the local biota” and were centered on immediate human needs. For this reason, the alleged medical and culinary properties of plants and animals remained the two most prominent organizing principles of Japanese taxonomies. Second, the individual taxons, the taxonomic qualities that defined them, and the broader categories that hierarchically ordered them “reflect gross morphological patterns that subsume any number of generic-speciemes,” ones recognized as commonsense by most people. But this commonsense understanding of the natural world did have its limitations. That is, relying on human cognition, most peoples around the globe naturally classified wolves and dogs as taxonomically similar species; but “post-rational” symbolic speculations, ones culturally generated, then “go beyond the immediate and manifest limits of common sense” to imbue such animals, even though taxonomically similar, with conflicting meanings. Thus, though their DN...