![]()

CHAPTER ONE

HYBRID CHINESE PLACES IN A FORMER COLONIAL CAPITAL

ALTHOUGH Rangoon was designed by the British as a grand commercial and administrative center to inspire awe, the Rangoon of today evokes little of that grandeur in its damp decay. Navigating my way through the city, I focused much of my attention on the ground to avoid stepping into gaping holes or tipping up a loose paver and thereby falling into the fetid sewage that ran just below the sidewalks. In addition, there were usually street vendors who had spread their wares halfway across the sidewalk and shoppers who stopped or crouched down to examine potential purchases, further limiting the space for movement and requiring even more vigilance. In this maze of obstacles where I was rarely able to look up, the neoclassical, Victorian, Queen Anne, and eclectic Western-influenced architecture was rendered a faint, moldy, and only half-noticed backdrop. At eye level, the brick and masonry work of colonial architects and builders was mostly masked by rusty metal gratings, layers of flaking paint, and false modern facades that had been hastily attached to create new shop fronts and small eateries. The few structures that retained their original Italianate or Renaissance facades were well worn, with softened corners and surfaces stained with soot, mold, and betel nut spit. These streets and sidewalks that were once designed to facilitate the movement of goods and people in order to produce profits for the British Empire now seemed intent on thwarting everyday movement and commerce.

Despite these challenges, Rangoon residents traverse the streets of the former colonial capital with aplomb, apparently unperturbed by the broken sidewalks, tangled webs of electrical wires, and potholed roads. Under the willful neglect of the municipal and national governments, the degradation of Rangoon’s urban environment is only one of a number of obstacles confronting their daily lives. Compared to infrastructural issues such as frequent power outages, inconsistent water supply, and clogged sewers, the aesthetics and functionality of Rangoon’s streets are minor nuisances.1 Everyone, regardless of ethnicity or descent, has learned to make do with the limited services provided by the government.

This making do is not the passive acceptance of the dominant power structure but the use of creative tactics to sustain life in the interstices. As defined by Michel de Certeau, tactics are the makeshift maneuvers of the disenfranchised, exercised within strong constraints, to create momentary opportunities. In contrast, strategies are the comprehensive plans and policies of the powerful that seek to define absolute order and regulate physical and social space.2 In Rangoon, the unequal relations between the government (both colonial and postindependence) and its subjects are evident in the rational, rectilinear downtown core and the way contemporary Rangoonites inhabit and modify that rigid framework.

RANGOON: THE MODERN COLONIAL CAPITAL

Rangoon was explicitly designed as a capital city to serve the needs of the colonial state: to encourage trade and instigate order in a newly conquered territory. By the early part of the twentieth century, Rangoon was usually described by British officials as “the only large Indian city which has grown up on a scientific plan” and was rated as “a study of modern urban development.”3 However, through the eyes of the colonized, Rangoon was a doubly colonized city that was artificially implanted. Passing through the city in 1916, Indian Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore wrote: “This city has not grown like a tree from the soil of the country . . . [it] floats like foam on the tides of time. . . . I have seen Rangoon, but it is mere visual acquaintance, there is no recognition of Burma in this seeing . . . the city is an abstraction.”4 He lamented that colonial commerce had dominated and determined the character of the city and noted that Indians, as the overwhelming majority, had essentially colonized the Burmese once more, almost in lockstep with the British Raj. As a later conquest of the British Empire, Burma was ruled according to the precedents established in British India, and its capital, Rangoon, was laid out according to so-called scientific principles that had been formulated to solve the environmental and public health problems of nineteenth-century London. The Industrial Revolution, along with other factors, led to a dramatic increase in London’s population, which overwhelmed the capacity of the city to serve its residents and resulted in unsanitary slums, air pollution, increased crime, and rampant spread of disease. To solve these problems, Victorian reformers and government officials applied the science of their day, advocating wide and straight streets that could become the tools “to rout dangerous vapours as well as dangerous criminals.”5 These principles were applied indiscriminately to Rangoon as British officials sought to create an international port befitting and benefiting the empire.

As with many colonial and capital cities such as Bombay, New Delhi, Singapore, and Brasilia, the conquered landscape was seen as a tabula rasa to be shaped at will in service of the ruling elite. The physical form of Rangoon would be molded not only to reshape the native environment that was seen as primitive and unsightly but also to transform the indigenous people into proper British subjects. The order of Rangoon society would be determined by the rational order of the city. Veiled behind the pragmatic goals of promoting trade in order to increase England’s dominance in the world economy and rendering the city more easily ruled through scientific rationality, the design of Rangoon was to transpose British civility to a colonial outpost, to encapsulate all the colonial territories into the British world order.6

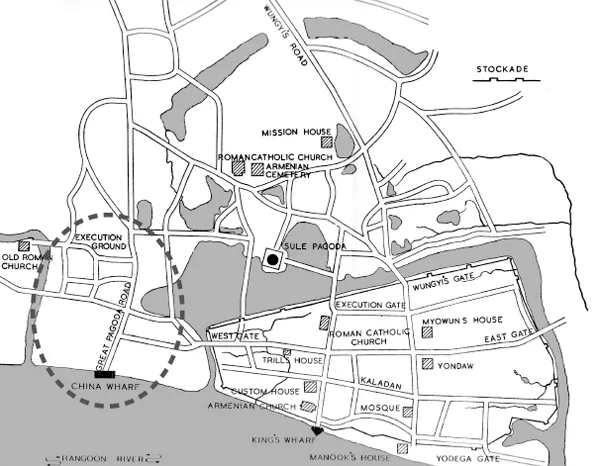

Rangoon and Lower Burma as a whole were seized by British forces during the Second Anglo-Burmese War, which started in April 1852. Even before the first commissioner, Colonel Arthur Purves Phayre, arrived in December 1852, the riverfront had been identified as the source of future growth and planned accordingly. The first plan proposed by Dr. William Montgomerie, the superintendent surgeon during the war, reveals that the implicit approach to city design was to surgically remove undesirable elements. This plan was later modified by Lieutenant Alexander Fraser and submitted to Colonel Phayre for consideration. Both officers advocated a rational gridiron plan composed of wide streets to avoid the congestion that was seen as the root cause of inefficient transportation and inadequate sanitation. They, along with their brethren in England, saw the need to discourage the spread of bodily disease and societal disease—illness and crime—through proper city planning. This grid plan mandated a wide strand along the river that would be 150 feet wide and another main road that ran from the wharf north to the Shwedagon Pagoda that would be 100 feet wide. Phayre agreed with this layout that emphasized the riverfront strand and wrote to his superior in Calcutta that the design of Rangoon would be “with reference to the lines of these two [main] roads, which will run at right angles. At intervals of about 750 feet there will be roads of 100 feet broad, running from the strand road north, and intersected by roads of similar width running east and west. The intervening spaces between these main roads will be divided by three roads of 30 feet width each.”7 Phayre also decided that wider streets would be named and narrower streets numbered, clearly marking the hierarchical spatial order imposed on the city (Map 1). This grid of major and minor streets was not unique to Rangoon, for Dr. Montgomerie, having previously served in Singapore, based his schematic design on the latter’s form. As with Singapore, the strand in Rangoon was seen as the public face of the city that would properly impress travelers and “spur an aesthetic response which would reinforce the solidity and permanence of its European and commercial quarter.”8 This grand facade’s audience was other Europeans arriving by sea, not the local inhabitants, just as the promotion of trade was intended to benefit European and other foreign merchants, not the local Burmese.

The network of regular streets not only made Rangoon visually more aesthetic, more in line with good taste; it also rendered the city more readily ruled, more legible within British conceptions of order and manageability.9 Wide and straight streets provided few hideouts for potential criminals, and the clear lines of sight made it easier for police to capture dacoits (bandits). This rectilinear grid also produced standard lots that could be systematically sold and taxed or otherwise regulated. Soon after arriving in Rangoon, Phayre declared all land in and around Rangoon government property, citing the destruction of Rangoon immediately before the war in 1852 as just cause for assuming state ownership. On this conveniently blank slate, Fraser and Phayre planned 25 blocks that were subdivided into 172 lots per block, which resulted in 4,300 lots that would be available for sale. They assigned an alphabetical letter to each block, and the lots within these blocks were numbered, creating an ultimately orderly system through which to govern the city.10 “Phayre and his officers would have absolute knowledge of the town’s geography, conveniently reduced to numbered and lettered parcels which could be quickly located on a map and readily understood.”11 Furthermore, Phayre’s ruling on property rights meant that the government would supervise and direct the distribution of all land. “Private citizens were only allowed on their new property by the grace of the government’s law. Living and building in the town was being made constantly available to government scrutiny.”12

In fact, these lots were divided into five different classes, with the lots closest to the river, along Strand Road, commanding the highest prices. The riverfront, the most valuable property, was reserved for official buildings that would present a majestic facade to Europeans arriving by sea. The next three classes of property were valued according to their distance from the river and proximity to existing wharves.13 In addition, specific requirements were dictated for different classes. All buildings in the first-class lots near Strand Road and in the business district had to be made of brick, with pukka or tiled roofs.14 Regardless of class, all owners of all lots would have to build “a good and substantial bona fide dwelling house or warehouse” within one year of purchase or the property would be confiscated.15 This latter regulation was initially implemented to prevent speculative buying but also to mandate a particular kind of physical and social environment. Only the wealthy could afford to both buy a lot and build on it according to regulation. Brick was not a common material in Rangoon and required significant skill and investment to produce. The local building materials of bamboo and thatch were deemed too flimsy and primitive, counterproductive toward creating an orderly society. Phayre and his officers thought that living in more substantial houses that had to be purchased or rented would teach the Burmese to value personal property and take proper measures, using doors and locks, to protect their possessions. They were frustrated with the high incidence of theft and placed blame on the Burmese, who were seen as incapable of comprehending the standards of prevention or protection. Rangoon’s magistrate wrote, “Until their unsubstantial tenements of bamboo and leaves are replaced by houses capable of resisting the efforts of burglars and thieves, by the simple process of locking the door, we cannot expect that temptation will be less strong.”16 These stipulations were a means to maintain control over the real estate in Rangoon and to mold proper British subjects.

This spatial and legal structure instituted a new social order that would have been completely alien to the local residents. Before the British designated Rangoon as their center of operations in 1852, Rangoon was a loosely organized town that had grown organically around the swamps and hills in the area (Map 2). Historically, this town was ruled by the Mon people and was known as Lgung or Dagung, which became “Dagon” in Burmese. In 1755, Alaungpaya, a Burmese king, conquered the town and renamed it Rangoon, meaning “the end of strife” in the Burmese language, to mark the cessation of warfare between the Burmans and the Mon. Although Rangoon served as a port for the Konbaung dynasty (the last Burmese kingdom, 1742–1885), it never rose to prominence as a regional port because it was prone to flooding and because the trade of silk and spices bypassed Burma, going straight from Java and Melaka to Calcutta.17 In addition, the town was never significantly built up, because ports and trade towns in Southeast Asia were generally conceived of as temporary places that expanded and contracted according to the vagaries of trade.18 A stockade with a wungyi (minister) had been established next to Rangoon River, but there were few buildings and the irregularity of the sparsely populated town struck the British as sadly inadequate.19

Map 2. Alaungpaya’s town showing precolonial Chinese settlement. Based on B. R. Pearn, A History of Rangoon.

For those who moved to British Rangoon from central Burma, the city would have been just as alienating. The only planned cities in precolonial Burma were sacral cities such as Mandalay, which was explicitly laid out in the form of a mandala to represent the cosmic order on earth and thereby proclaim the legitimacy of the Burman kings.20 In contrast, the rectilinear grid of Rangoon was focused on the secular power of commerce and the authority derived from international capitalism and wealth. Almost everyone came from villages that were oriented toward the local Buddhist monastery, which was placed at the head of the village, and where the location of one’s home was determined not by law or a foreign government but by the natural resources in the area.21 In this context, the straight avenues and strictly delimited lots of Rangoon would have imposed an order unlike any the Burmese had experienced. Furthermore, Burmese people were mostly excluded from the planned city because the prici...