5 Winning by a NOSE: The Structure of Persuasion

IN AN ORGANIZATIONAL SETTING, PEOPLE WRITE for one of three reasons—to inform, to evaluate, or to persuade. For each of these purposes, there is a structural pattern that will produce the best results. You can think of these structural patterns as templates for delivering content in the right order. Keep in mind, however, that these are not templates created by English teachers or document designers. Rather, they arise from the brain of the reader. They are part of our innate mental apparatus.

The human brain is hard-wired to look for content in a specific order, depending on what purpose we will make of the message. If you use the wrong pattern in organizing your content, you will get the wrong results. It’s like trying to drive a nail with a screwdriver—you might eventually get the job done, but it’s going to be a lot harder than it has to be. In Chapter 2, I asked you to read an executive summary and make one simple decision: is it worth keeping or not? By asking you to make a decision, I established intentionality in your reading process. You were approaching the task with the goal of making a decision, so you were looking for certain kinds of content in a very predictable order. If I had given you a different challenge, such as reading the executive summary to determine how many factual statements the bank made about itself, you would have looked for a different pattern. And you would have approached the task differently.

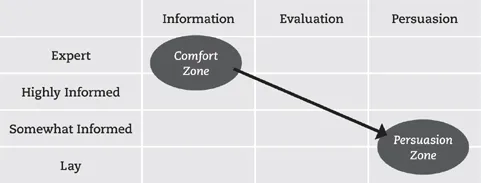

Information doesn’t create momentum toward a decision. Persuasion does. Unfortunately, people are often most comfortable providing information, particularly when they are speaking or writing to an audience that knows almost as much about their topic as they do. (See Figure 5-1.) That doesn’t work. We have to move out of our comfort zone and into the persuasion zone—a different structural pattern and a less-expert audience.

Figure 5-1. Move out of the Comfort Zone to Persuade Effectively

The purposes that govern informing, evaluating, and persuading are so different that using one mode when your purpose calls for the other will condemn your efforts to failure. So let’s distinguish among the primary reasons people write in a business setting and look at how those different purposes require different approaches.

Information

The first and most common reason people write is to inform. They’re writing to share content with somebody who needs it. The ideals of informative writing are clarity and conciseness, and the focus is on transferring the information quickly and easily.

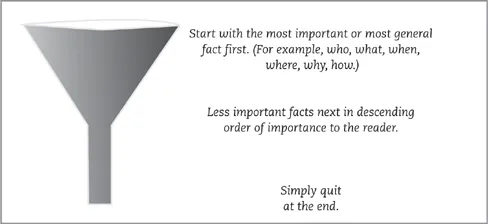

The best way to communicate informatively is to use the pattern taught in journalism classes: the funnel. (See Figure 5-2.) Start with the fact or set of facts most important to the reader. In journalism, that’s often who, what, when, where, why, and how? Then go to the next most important fact. Then the third level of importance, the fourth, the fifth, and so on, until there is nothing left to say. By structuring your document this way, you allow your readers to stop reading as soon as they have seen enough.

The challenge in writing informatively is to figure out which fact is most important to the reader. Too often we assume that everybody will have the same orientation to the material that we have. But that can be a big mistake. Even a single reader is likely to have different interests in the same story. If you pick up a copy of the Wall Street Journal, you’ll look for a different set of facts in the lead paragraph of an article than you would if you picked up a copy of People that contained an article about the same story. From one publication we expect a financial orientation, while the other will give us the human interest angle.

The most common mistakes in presenting information are writing chronologically, which usually leads to wordiness, or starting with facts that matter to the writer but not to the reader, which usually leads to confusion or false emphasis. Another error is to place important content at the end of an informational piece of writing. People tend to scan this kind of writing from the top down, so they bail out of the process when they think they have gist of it. They won’t see the content you put at the end unless you work hard to highlight it.

Figure 5-2. The Funnel-Shaped Structure of Informative Writing.

We use informative writing in proposals when we answer the simple, pro forma kinds of questions that often appear in RFPs—your headquarters location, names of top managers, or how many offices you have. Most of the time, these are just facts, not tactical differentiators that are going to help you win the business. When you believe the question being asked is simply a checkbox item, use informative structure to answer it.

Evaluation

The second reason businesspeople write is to evaluate something or somebody. A performance appraisal, a competitive analysis, an appraisal of an asset—in all of these cases, simply presenting the facts is not enough. What people want to know is what you think, what your opinion or value judgment is.

When they are offering a professional opinion, people are trying to interpret what the facts mean. This is particularly true when the information being offered is being compared to another set of related facts. For example, consider what happens in a court case when one side calls in an expert witness. Such a witness isn’t asked to establish facts about the case—“Where was the defendant on the night of July 15?” Instead, the expert witness is asked to offer an opinion about what a certain body of facts indicates: “On the basis of these facts, do you think the defendant is mentally competent?” “Do these actions match the accepted standard of care?”

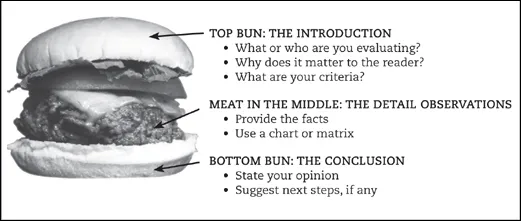

The pattern for evaluative writing is depicted in Figure 5-3, in which an evaluation is compared to a hamburger. The point of the illustration is that you need a top bun (the introduction), a bottom bun (the conclusion), and lots of meat in the middle. By contrast, informative writing doesn’t need an introduction to set the scene and it really doesn’t require a formal conclusion. To write an effective evaluation, however, you must begin with an introduction, in order to define your subject—what (or who) you are evaluating—and the criteria on which you are basing your evaluation. Then you need to present your observations and evidence. Finally you need to offer your opinion. If you follow that structural pattern, your opinion will sound logical and your evaluation will be easy to follow.

Figure 5-3. The Three-Part Structure of Evaluation.

Good examples of evaluative writing can be found in Consumer Reports. If you were thinking about buying a new camera or a refrigerator or snow tires, you could find articles there that would evaluate the various brands and models available. Because we trust the source, we usually skip the opening and middle and go right to the end of the article, which tells us which brand is the “best buy.”

Sometimes, though, you get an evaluative report in which the opinion is shocking or doesn’t make any sense. Suppose you are looking for an appraisal of a piece of real estate you own, perhaps to use it as collateral on a loan. Typically, a bank will want to get two appraisals of that property. You probably have a pretty good idea of what the property is worth, so if one of the two appraisals comes in at half the value of the other one, you’ll immediately turn to the body of the report to find out why they are so different.

We use evaluative writing in proposals when we are asked questions that involve comparing two or more approaches. Sometimes the question will be worded to ask for “strengths and weaknesses in your opinion” of a particular approach, technology, or other element of the solution. I have even seen RFPs that ask you to indicate what differentiates you from your competitors. Using the evaluative structure enables you to set up the terms of comparison so that you offer a reasonably objective opinion based on rational assumptions.

Persuasion

The third reason people write is to persuade. In this kind of writing you are trying to influence the audience so they are motivated to take action. Effective persuasion requires more than...