eBook - ePub

My Grandmother

An Armenian-Turkish Memoir

Fethiye Çetin, Maureen Freely

This is a test

Buch teilen

- 128 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

My Grandmother

An Armenian-Turkish Memoir

Fethiye Çetin, Maureen Freely

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Growing up in the small town of Maden in Turkey, Fethiye etin knew her grandmother as a happy and respected Muslim housewife called Seher.

Only decades later did she discover the truth. Her grandmother's name was not Seher but Heranus. She was born a Christian Armenian. Most of the men in her village had been slaughtered in 1915. A Turkish gendarme had stolen her from her mother and adopted her. etin's family history tied her directly to the terrible origins of modern Turkey and the organized denial of its Ottoman past as the shared home of many faiths and ways of life.

A deeply affecting memoir, My Grandmother is also a step towards another kind of Turkey, one that is finally at peace with its past.

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist My Grandmother als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu My Grandmother von Fethiye Çetin, Maureen Freely im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Sozialwissenschaften & Sozialwissenschaftliche Biographien. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Whenever I think of that January, I shudder; I feel cold. Somewhere deep inside, I begin to ache. When my mother wanted us to know that she was in great pain, she would put her hand on her left breast and say, ‘I ache here, just around here.’ Somewhere deep inside my heart, I ache in just the same way.

The high walls that enclose the cold mosque courtyard are made from massive stones that are blackened with age but undiminished; the icy funeral stone chills a person just to look at it, and there, on top of it, is a coffin. The slab and its pedestal have both been chiselled from the same great stone. The pedestal is so cold that when I touch it, I fear my hand will stick, so I draw back. It is as if this courtyard – these colossal stones, these giant walls – existed for no other purpose than to make a person feel helpless and bereft.

Whenever I see a funeral stone now, I shudder, no matter what the season, and usually I leave that place at once. But if I linger, it all rushes back – the mosque courtyard, the funeral stone, the freezing cold. And I begin to shiver.

It is night when Emrah rings. ‘We’ve lost our grandmother,’ he says. I already know she’s dead. In the morning, in the cemetery, in the place where they do the ritual cleansing (they call it a bath house, and so now these words, too, send a chill through me) the women wash down her body and when their work is done, they summon me so that we can say our farewells. I say goodbye to her cold body; I kiss her on the cheeks. On my lips I feel the chill that even now seems so ill-suited to her. I know she’s been placed in a coffin but I just can’t accept it. It feels like a dream. I cannot believe that my grandmother can be lying so still and helpless, inside that coffin. And neither can I believe how hopelessly the rest of us are going through the motions.

We wait with the women who are huddled together in the most sheltered corner of the mosque courtyard. As we wait, crying uncontrollably as we embrace each new arrival, someone rushes over to us from the huddle of men and in a panic-stricken voice, he asks:

‘Auntie Seher’s mother and father – what were their names?’

At first none of the women answer. Instead they exchange glances, as the silence becomes ever more awkward. And still the silence goes on, until one of the women, my Aunt Zehra, finally breaks it:

‘Her father’s name was Hüseyin, and her mother’s name was Esma.’

No sooner has my aunt said these words than she turns to me, as if to seek my approval, or so it seems to me.

Relieved to have extracted the answer he wants from this group of tight-lipped women, the man turns back to the all-male crowd that has gathered around the funeral stone, and as he does so, these words rip from my heart through the silence:

‘But that’s not true! Her mother’s name wasn’t Esma, it was İsguhi;! And her father wasn’t Hüseyin, but Hovannes!’

This man has taken it upon himself to furnish the imam with the names of the deceased’s parents, and now, just as he prepares to do so, I am declaring those names to be false; he turns around, fixing me with a hostile stare as he struggles to understand what I have said.

My aunts begin to cry. Then all the other women join in, as if my aunts have given them a sign. Usually crying is contagious. I can’t stop my tears either. I fall silent, anxious that I might make those around me cry even more if I repeat my accusation or stand by my words. I bow my head as I cry inside, ashamed that even here we have to carry on pretending.

The man stares at the huddle of weeping women for a while longer, and then he gives us a look, as if to say, ‘Women!’ as he walks away from us.

For the same reason that her mother’s name wasn’t Esma, and her father’s wasn’t Hüseyin, my grandmother’s real name was not Seher, but Heranuş. This, too, I found out very late.

At the time of Heranuş’s childhood, Habab1 was a large village of 204 dwellings, situated within the boundaries of Palu and the district of Ergani-Maden. The village boasted two churches and one monastery.

Heranuş was the second child to be born to İsguhi; and Hovannes2 Gadaryan. Because she was born after the death of their first child, Markrit, Heranuş was raised with great care. Two more children arrived soon after her. When she was still a tiny girl, Heranuş helped look after these two boys, whose names were Horen and Hirayr.

Heranuş’s father Hovannes was the third of seven children and one of six boys. His two older brothers were named Boğos and Stepan, his younger brothers were named Hrant, Garabed, and Manuk, and his only sister was named Zaruhi. The family became bigger still after the eldest brothers married. At an early age, Manuk was afflicted by an unknown malady from whose clutches he was unable to wrest himself free. The entire village went to church to pray for his recovery but to no avail. Yet just as the last hope was dying away, Manuk returned to life. The entire village celebrated, for the Gadaryans were its most important family.

Heranuş’s grandfather, Hayrabed Efendi, was a highly respected teacher who was known and loved throughout Palu and its environs, as well as Ergani-Maden, and Kiği. He was known as a good man; people listened to what he said. In those days there were colleges in Ergani-Maden and Kiği to which children went to study after finishing primary school. Hayrabed Efendi taught in these colleges. He was a trustee of the church and served as its choirmaster. It was said that his brother, Antreas Gadaryan, was a distinguished teacher who was even better known than he. If people had trouble reading old Armenian texts, they would take them to him. No matter how difficult it was, Antreas would decipher it in no time. In his book entitled Palu and its Traditions: its education and its intellectual life,3 Father Harutyun Sarkisyan wrote these words about him: ‘The educator Antreas Gadaryan was a child of Anatolia … he was short and spoke very little, but under his thick eyebrows, his bright eyes shone with an intelligence that impressed all those who met him from the moment they made his acquaintance.’

The Gadaryan and Arzumanyan families both had roots in this crowded, long-established village. The Gadaryans’ Hovannes was fond of their neighbours’ eldest daughter, who was an Arzumanyan, and who, like his own mother, was named İsguhi;; a day arrived when his father asked him whether or not he wished to marry their neighbour’s daughter. He said ‘yes’ without hesitation; he was so happy he could almost fly. İsguhi;, who was six years younger than him, also came from a big family. She was the eldest, with two younger brothers, and four younger sisters. After Hayk and Sirpuhi came the twin girls, Zaruhi and Diruhi. The youngest was Siranuş.

İsguhi’s mother Takuhi was the village healer. It was said that she had as much knowledge as a doctor and was sought after throughout the area when there was a case of broken bones. The two families were on the best of terms, so everyone was in favour of Hovannes marrying İsguhi;. So it was a love-match, and Heranuş was their second-born. Her godfather was Levon Eliyan, whose own forefathers had been godfathers to many other Gadaryans over the years.

Heranuş was a child who learned fast, and she also had an ear for music. Because she loved to sing, her repertoire was always growing, and she would also try to teach whatever she learned to her sisters, brothers, and cousins. But there was one song she loved more than any other, and she would return to it as often as she could. And when her grandfather sat her on his lap to teach her new songs, he would stroke her hair to let her know how much he liked the way she sang them. She was usually the one to start games; she was the leader, the one who showed the way, and the other children were happy to go along with her.

In 1913, the year Heranuş started school, her father and two of her uncles went to America, in the hope of working to save enough money to set themselves up in business, as a number of their relatives had already done. In those days, many men in the village dreamed of going to America, to work amongst the rich and become wealthy themselves. The first to go to America was Uncle Boğos. Uncle Stepan followed. The next to undertake the long and tumultuous journey were her father and Uncle Hrant.

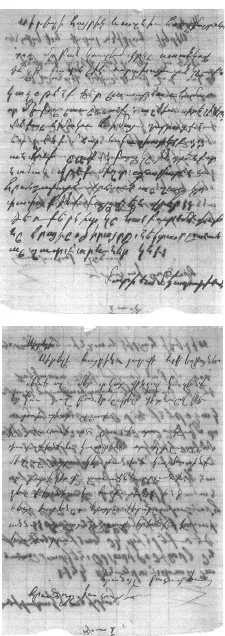

Heranuş started school the same year as her Uncle Stepan’s daughter Maryam, and as soon as she had learned how to read and write, she wrote a letter to her father and her uncles. Maryam wrote her own message on the other side of the same sheet of paper, which they sent to America.

These are the lines that Heranuş wrote on her side of the paper:

Dear Father, Dear Uncles,

We too hope to use our feeble pens to jot down a few lines and tell you how we are, because we know this will please you.

We hope you are well, we all keep hoping and praying that you are well. And we are going to school every day, and we are trying very hard to be well-behaved children.

I kiss your hands, and so do Horen, Hirayr, Jirayr, and Maryam.

Anna misses you very much and she sends you kisses.

Heranuş Gadaryan

The Jirayr she mentions in the letter was, like Maryam, her uncle Stepan’s child. Anna was her mother İsguhi;’s name within the family. On the other side of the paper, Maryam wrote:

Dear Father, Respected Uncle,

I want to jot down a few lines and tell you how we are, because maybe this will please you.

We pray for you to be well, so that we can be well too. Dear and respected fathers, be sure that we never shy away from school, and we are working hard.

Do not worry. But we ask you to please keep writing us letters. We wish that our big Ohan Ahpar and Hrant Ahpar4 would write us letters, but they don’t.

I kiss your hands. Horen, Hirayr, Jirayr, Nektar, and Anna also send their greetings.

Maryam Gadaryan

And so it was that the cousins Heranuş and Maryam sent their good news to their fathers and uncles on two sides of the same sheet of paper. But the beautiful handwriting on one side of the sheet is immediately noticeable. Its words look like flawless pearls; they come from the hand of Heranuş.

Heranuş wrote on one side of the sheet of paper, and her cousin Maryam on the other. The letter was found in Hovannes’ wallet after his death. See p. 8 for translation.

Hovannes and İsguhi; loved to dance, and if there was a celebration in the village, they would be there; they would become one with the rhythm of the music and dance the halay for hours on end. When her husband went to America, İsguhi; would attend weddings and other village festivities with her uncle, to dance the halay with him.

In the winter, when the nights were long, the dervishes would come to visit, and that was when the village celebrated most boisterously. The villagers would form a circle around the dervishes, to watch with fear, surprise and adulation as they performed with their skewers and burning braziers. They would send their iron skewers in through one cheek and out the other, but without spilling a single drop of blood. They would take the burning braziers into their arms but their arms and their hands would not burn. Heranuş found the whole business shocking. One day, while she was at school, her brother Horen was scalded by boiling water, and there were terrible burns on the left half of his chest and on his left arm. When Heranuş looked at the burns on her brother’s body, she had trouble believing what she’d seen the dervishes do, and would spend long hours at night trying to make sense of it.

The Gadaryans lived in a spacious two-storey house with many rooms and a spacious courtyard. Heranuş was good friends with the dog that guarded the house and enjoyed playing with him. Years later she would tell, over and over, the same wistful stories about this courtyard and the games she played in it with her...