![]()

PART I

Swimming Culture

![]()

Chapter 1

Atlantic African Aquatic Cultures: A Cross-Cultural Comparison

The first recorded interaction between Europeans and Sub-Saharan Africans occurred in the water. Off Senegal in c. 1445, Portuguese sailors, coming from a maritime culture that devalued swimming, were astounded by the aquatic expertise of Wolof-speaking fishermen. Sailors lured fishermen in six canoes close to their ships to capture and interrogate them. As a Portuguese longboat overtook one dugout, the fishermen “leapt into the water.” It was with “very great toil” that two were captured, “for they dived like cormorants.” Though the incident occurred well offshore, the others rapidly swam ashore.1

From the fifteenth through the late nineteenth century, the swimming and underwater diving abilities of African-descended peoples regularly surpassed those of Westerners. Most white people could not swim. Those who could were inexpert. To reduce drowning deaths, some philanthropists, beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, advocated swimming as a means of self-preservation. In 1838, Sailor’s Magazine, a New York City missionary magazine, published the inscription of a city placard titled “Swimming.” It read: “For want of knowledge of this noble art thousands are annually sacrificed, and every fresh victim calls more strongly upon the best feelings of those who have the power to draw the attention of such persons as may be likely to require this art, to the simple fact, that there is no difficulty in floating or swimming.” Regardless, in 1899, swimming advocate Davis Dalton lamented: “Few persons know how to swim.”2

Sources indicate that many Africans were proficient swimmers who learned at a young age. Aquatics were woven into people’s spiritual beliefs, economies, social structures, political institutions, and worldviews, shaping societal relationships with waterscapes. A comparison of African- and European-descended peoples reveals striking differences in valuations and practices that suggest the African origins of slaves’ aquatics. Swimming pervaded Africans’ muscle memory. Along with walking, talking, and reading, swimming becomes virtually intuitive, once learned, and was one of the easiest skills to carry to the Americas.

Ancient Europeans were proficient swimmers, but from the medieval period until the modern period and for numerous reasons they discouraged swimming. Christian texts characterized the ocean as the unfinished chaos preceding civilization and “realm of Satan,” while stories of the Great Flood and drowning of Pharaoh’s army depict water as an “instrument of punishment.” Catholic and Protestant epic stories of colonization described Satan dispatching sea monsters to destroy Christian colonists seeking to expand Christendom. Writers routinely equated water to hell and swimming to eternal torment, describing it as a futile act and an allegory for the loss of salvation. Jesus, for example, admonished His followers to be “fishers of men,” pulling them from waters of damnation. In 1602, a Jesuit compared sinners to “a swimmer who, extending and contracting his arms, displays the gesture of a man utterly vanquished and in despair. Thus Saint Jerome, Adam, &c., compare [the ungodly] with a shipwrecked swimmer in the sea because, just as such a one is tumbled about in the depth of the sea, so the ungodly, being shipwrecked from salvation, are tumbled about in the abyss of Gehenna,” or “hell.”3

Medieval swimming was regarded as a fruitless struggle against nature, while changes in warfare favoring knights precipitated a shift in attitudes regarding its utility.4 Doctors discouraged immersion, as water purportedly upset the balance of the body’s humors, causing diseases. Since swimming was generally performed nude, Catholic officials admonished it for moral reasons.5 Furthermore, many believed waterways were filled with “noisom vapours” and ravenous creatures. By the fourteenth century, the crawl was virtually forgotten.6

White authors indicate that few European-descended people could swim well enough to negotiate moderate turbulence. Advocates recognized that some could swim if permitted to strip nude and enter calm waters while keeping their heads above water. They encouraged proficient swimming in which individuals resurfaced if submerged during maritime accidents and swam until rescued.7

More specifically, Europeans preferred variants of the breaststroke, concluding it was the most civilized and sophisticated stroke. When performed correctly, both arms are extended forward and pulled back together in a sweeping circular motion, the legs are thrust out and pulled together in circular frog kicks. Early modern whites used forms akin to the dog paddle, keeping their heads above water, letting their legs drop almost vertically, which reduced speed and endurance. During the sixteenth century, theorists began publishing treatises that advocated elementary versions of the breaststroke, believing that swimming should be graceful and sedate.8

Theorists neither swam themselves nor consulted swimmers. Instead, theories largely evolved as analytical speculation on “ideal forms of swimming” that had little influence on swimming practices.9 Many speculated on how swimmers could cut their toenails, catch birds, or perform other still unperfected activities. Some considered how to escape unlikely scenarios like “lions, Bears, or fierce dogs lurking in the river” Thames.10

Observers, including Benjamin Franklin, referenced the breaststroke as the “ordinary,” or white, method.11 White people became averse to the crawl, also called the “freestyle” or “Australian crawl,” because it generated splashing, and they felt swimming “should be smooth and gentle.” The crawl was judged savage while the breaststroke, which was relatively basic, was deemed refined and civilized.12 During the 1830s, George Catlin documented Amerindian culture in print, drawings, and paintings, revealing how whites appreciated the crawl’s speed while dismissing it as uncivilized. In North Dakota, he wrote: “The mode of swimming amongst the Mandans, as well as amongst most other tribes, is quite different from that practiced in those parts of the civilized world, . . . The Indian, instead of parting his hands simultaneously under his chin, and making the stroke outward, in a horizontal direction,” used the “bold and powerful” crawl.13

Fear of submerging one’s face prevented many whites from becoming proficient swimmers. In 1587, theorist Everard Digby guided readers into the water. Paraphrasing Digby, Franklin encouraged readers to “walk coolly into it till it is up to your breast, then turn round, your face to the shore, and throw and egg into the water between you and the shore.” The real test came when readers were told to submerge their faces “with your eyes open” while retrieving the egg. Annette Kellerman, an early twentieth-century movie swimming performer, believed swimming was an ideal sport for women. She too encouraged people to relinquish their fear of water by getting wet: the first hurdle in transforming land-bound people into swimmers.14

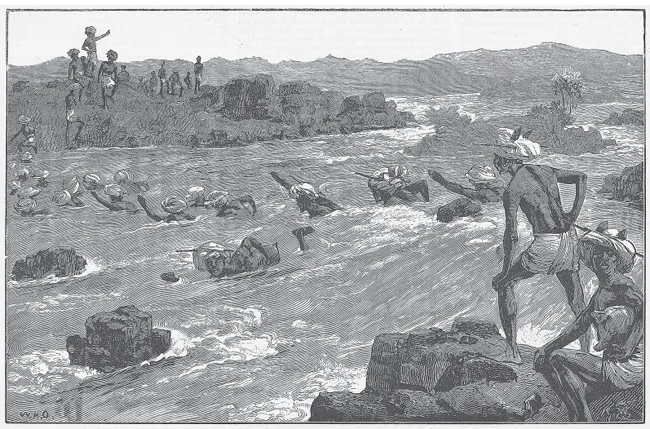

Figure 1. Dongola Men. This image depicts Dongola men in the Sudan using the “high elbow” of the crawl while crossing rapids, illustrating the widespread use of this stroke within Africa. These men were part of a British military expedition. British troops apparently could not swim well enough to traverse the river and were shuttled across in boats. “The Nile Expedition for the Relief of General Gordon,” Illustrated London News, 85 (October 4, 1884), 316; article on 318. Author’s collection.

In contrast, Africans created immersionary cultures that valued aquatics, which we must consider since humans do not instinctively swim. Swimming transforms water into a “mystical medium,” permitting swimmers to glide weightlessly through liquid infinities as body and water slip into fluid motion. Africans treated swimming as a life skill and a method of personal cleanliness, devising efficient techniques for traversing surface and submarine strata. Swimming was a sensual experience, blunting some senses while accentuating others to provide an otherworldliness. It was a rhythmic, dynamic pursuit that defied terrestrial forms of locomotion, stimulating the skin’s nerve endings as they came in contact with warm tropical waters and cool surface breezes. “Swimming cultivates imagination,” permitting people to focus their thoughts or set them adrift. It has long been described as “poetry in motion;” allowing humans to feel “almost capable of soaring in the air.” One advocate felt that the “experienced swimmer when in the water may be classed among the happiest of mortals in the happiest of moods, and in the most complete enjoyment of the most delightful of exercises.”15 Yet, we must not romanticize swimming. Unlike walking, swimming is a struggle for survival, and, in the Americas, became a form of exploitation.

Africans perfected variants of the crawl, concluding that its alternate overarm stroke and fast scissors kicks, which make it the strongest and swiftest style, was the proper method. Nearly every white traveler was amazed by Africans’ fluencies. In 1455, Venetian merchant-adventurer Alvise da Cadamosto relayed that those living by the Senegal River “are the most expert swimmers in the world.” He asked if “anyone who could swim well and was bold enough” would “carry my letter to the ship three miles off shore,” as storm-swept seas prevented dugouts from making the passage. Two volunteered for what Cadamosto believed an “impossible” task. After “a long hour,” one “bore the letter to the ship, returning with a reply. This to me was a marvelous action, and I concluded that these coast negroes are indeed the finest swimmers in the world.”16

Other travelers agreed and routinely claimed that Africans were better swimmers than Europeans. Dutchman Pieter de Marees described Gold Coast Africans’ crawl during the 1590s, writing that “they can swim very fast, generally easily outdoing people of our nation in swimming and diving.” Comparing the Fante’s crawl to Europeans’ breaststroke, Jean Barbot asserted, “The Blacks of Mina out-do all others at the coast in dexterity of swimming, throwing one [arm] after another forward, as if they were paddling, and not extending their arms equally, and striking with them both together, as Europeans do.” Similarly, Robert Rattray said Asante “are very fine swimmers and some show magnificent muscular development. They swim either the ordinary breast stroke [like Europeans] or a double overarm with a scissor-like kick of the legs.”17

Impressed white people frequently compared African-descended peoples to marine creatures, tritons, and mermaids, often proclaiming them amphibious. In 1600, Johann von Lubelfing averred Africans “can swim below the water like a fish.” Thomas Hutchinson concluded, “The majority of the coast negroes . . . may be reckoned amphibious,” proclaiming women “ebony mermaids.”18 New World slaves were similarly likened to aquatic animals. Edward Sullivan concluded that black Bahamians were “an amphibious race.” In 1796, George Pinckard observed a Barbadian slave, exclaiming: “Not an otter, nor a beaver, nor scarcely a dolphin could appear more in his element.” After remaining submerged “for a long time” he surfaced, appearing “as much at his ease, in the ocean, as if he had never breathed a lighter, nor trodden a firmer element.” Others equated them to nymphs, mermaids, and tritons.19

Many Africans believed drowning was dishonorable, with maritime disasters juxtaposing African and European abilities. Typically when boats sank, those of African descent saved themselves. One of two things usually happened to whites: African-descended peoples saved them or they drowned. U.S. Naval officer Horatio Bridge provides examples of both. In 1836, ten U.S. sailors drowned when their boat swamped and capsized in the Liberian surf. In 1843, Bridge noted that marines disembarking in Liberia upset the canoe they traveled in. “Unable to swim, [at least one] was upheld by a Krooman.” One year later, five whites and five Kru were aboard a boat that “capsized and sunk. The five Kroomen saved themselves, by swimming, until picked up by a canoe; the five whites were lost.”20 No account of a white person swimming to save a drowning African has been found.

Some Africans used spiritual beliefs to explain high rates of white drowning, concluding that deities drowned Europeans for their transgressions. In 1887, Alfred Ellis learned that peoples along the Gold Coast believed in “Akum-brohfo, ‘slayer of white men, whom he destroys by upsetting their boats.’ ” He felt this deity was “apparently introduced to account for the number of instances in which boats are capsized, the white occupants, encumbered with clothes, and either unable to swim or less powerful swimmers than the black crew, are the only persons drowned. Since the blacks, though equally thrown into the water, escape, while the whites perish, it is evident to the native mind that the god has a special dislike for the latter.”21

Africans similarly construed shark and crocodile attacks. Some believed that whites provided a line of defense against attack, as their skin shimmered in the water like fishing lures. While on the Gambia River, Richard Jobson noted that canoemen refused to swim until he “leapt into the water,” saying “the white man, shine more in the water, then they did, and therefore if Bumbo [crocodile] come, hee would surely take us [whites] first.” Likewise, peoples in Sierra Leone believed sharks were attracted to whites.22

Some Westerners equally sought religious explanations for African aquatics. The Great Flood narrative was used to facetiously explain Africans’ expertise, as reported by an American woman in East Africa: “Respecting the amphibious traits of the natives ...