![]()

CHAPTER 1

Slavery and Empire on the Wild Coast

Although the African captives crammed into the holds of the Barbados Packet had no way of knowing it, the ship’s captain wanted them to survive the Atlantic crossing. Adam Bird was a veteran captain and one of a hundred or so Liverpool-based slave traders that sailed to Africa in 1805. He knew that every person who died during the voyage represented a financial loss. Bird and his thirty-four-man crew began trading near the mouth of the Grand Mesurado River, a sparsely populated region in what is now Liberia, in November 1805. Within a few months they had transformed their ship into a floating prison for 270 captive Africans. Bird was probably eager to set sail, given the higher than average likelihood of revolt on the Windward Coast, the hazards of sailing in a region with few natural harbors and steep beaches pounded by heavy surf, and, most important, because the longer he stayed, the more captives he would lose. As Bird knew all too well, transporting human commodities was a risky business infused with death.1

As the ship full of captives followed the trade winds south into the Atlantic, it was not destined, as its name suggested, for Britain’s oldest West Indian colony, where the soil had been depleted after a century and a half of intensive sugar cultivation. Instead, it headed toward a former Dutch colony five hundred miles south of Barbados that had recently become the new frontier of Caribbean slavery: Berbice. By late March 1806, after some two months at sea, the Barbados Packet approached its destination. Navigation along the Guianas—a nine-hundred-mile stretch of muddy coastline between the Orinoco and Amazon Rivers—was dangerous and difficult. The brackish water was shallow, and a seemingly endless series of shoals, sandbars, and mudflats shifted faster than cartographers could update their maps.2 Thousands of rivers and creeks carved through the continent, dragging silt dozens of miles into the Atlantic, but none provided a natural harbor.

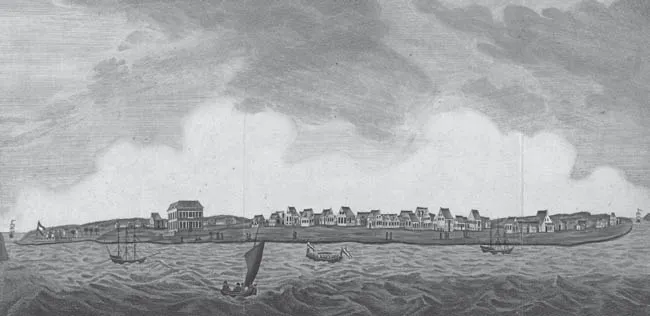

Figure 1. New Amsterdam and the Berbice River. Gezigt van de stad Nieuw-Amsterdam a Rio de Berbice, foldout color frontispiece in Abraham Jacob van Imbijze van Batenburg, Kort historisch verhal van den eersten analog, lotgevallen en voortgang der particuliere colonie Berbice . . . (Amsterdam: C. Sepp Jansz, 1807). This image represents Berbice’s capital and only town, New Amsterdam, near the time that Great Britain occupied the colony. The artist emphasizes the town’s frontier quality, depicting it as a thin strip of muddy land sandwiched between the Berbice River, which dominates the foreground, and uncultivated land immediately beyond. There are no discernable roads or wharf, a few dozen scattered buildings, and only a handful of pedestrians. The modest fort at the far left, near the Atlantic coast, protects the entrance to the Berbice River, the colony’s major artery. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

Even the captives, who had no experience with open-ocean navigation and no idea where they were headed, could see that they were nearing land. The first clue was the change in the ocean’s color, which transformed, as another British traveler observed, “from being hitherto as clear as an emerald” to “thicker and more impregnated with mud” as the ship neared the coast.3 But even once land was in sight, it offered few landmarks to help navigators. The “very low and woody land,” one captain cautioned, “appears in all parts so much alike, that the most experienced Pilots are frequently deceived.”4 A virtually endless line of mangrove forest backed by swampy savannas was only occasionally interrupted by sparse signs of human settlement: planters’ whitewashed homes, slaves’ thatched roof cottages, and fields of cotton and sugar that stretched to the horizon.5 Unlike his disoriented captives, Captain Bird was familiar with this coastline, having delivered his most recent cargo of slaves to Berbice’s western neighbor, Demerara, the previous April.6

Toward the end of March, the Barbados Packet reached its port of call: the mouth of the three-hundred-mile-long Berbice River, divided in two by Crab Island and guarded by the modest battery of Fort St. Andrews on the east bank. A couple miles upriver, sandwiched between the Berbice and its tributary, the Canje River, was New Amsterdam, the colony’s ramshackle capital. It was an unimpressive sight—scattered wooden houses and offices, a couple of brick buildings in disrepair, and unpaved streets bordered by canals.7 The few thousand residents of the town, most of whom were enslaved, probably smelled the Barbados Packet before they saw it, so bad was the stench of slave ships after months at sea. The blood, urine, vomit, and feces produced by hundreds of captives made a noxious mixture. Of the human cargo, 247 Africans had survived the Atlantic crossing, while 23 died somewhere en route, their bodies thrown to the sharks. Yet as Bird and his crew began preparing the survivors for presentation to potential buyers, he may have congratulated himself on a successful voyage.8 There had been no major outbreak of smallpox, yaws, or dysentery; no insurrection; and the 9 percent mortality rate was predictable “wastage,” a normal part of doing business in human flesh.

For Berbice’s European colonists, the arrival of the Barbados Packet was an exciting spectacle. They turned out in droves to buy new laborers or simply gawk at the newly arrived saltwater slaves. Few transatlantic ships and even fewer slavers landed directly at Berbice. The river’s channel was too narrow and shallow for large vessels. Moreover, just seventy miles to the west, captains found a better harbor, easier coastal access, and a larger market for slaves at the mouth of the Demerara River.9 Whenever a slave ship did arrive in Berbice, crowds gathered at the open space behind Government House, near the riverside “stelling” (wharf), treating it like a “holyday, or a kind of public fair,” according to one witness. Planters came from all over the colony, some with their families, “all arrayed in their gayest apparel.” As the naked Africans were forced to mount a chair, buyers scrutinized their bodies—were they strong or weak? sick or healthy?—“with as little concern as if they [were] examining cattle in Smithfield market.”10

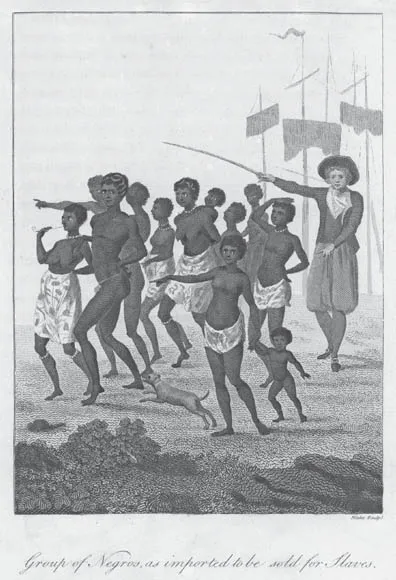

Figure 2. Recently arrived African captives. Group of Negros, as imported to be sold for Slaves, engraving by William Blake after John Gabriel Stedman, Narrative of a Five Years’ Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, 2 vols. (London: J. Johnson and J. Edwards, 1796), vol. 1, plate 22, following p. 200. This highly romanticized image of a group of smiling, semi-naked African captives represented a planter’s fantasy of the transatlantic slave trade. Ironically, Stedman’s text—where the engraving was published—acknowledged the physical suffering and emotional trauma that characterized the arrival of African captives in the Americas, even as Stedman defended slavery and the slave trade. To Stedman, the captives seen here, being driven by a sailor with a bamboo stick after arriving in Paramaribo, Suriname, were a “sad assemblage” of “walking Skeletons.” Nevertheless, he claimed that instead of the “horrid and dejected countenances” found in antislavery propaganda, he “perceived not one single downcast look” among them. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

The physical condition of the captives after months at sea was shocking even to those familiar with the brutality of Atlantic slavery. Although they had been washed, oiled, and shaved in a vain attempt to hide evidence of the violence that had brought them to Berbice and make them attractive to buyers, “the odour proceeding from their bodies was most unpleasant,” as a soldier observed after witnessing the sale of a slave ship cargo in 1806—the same year the Barbados Packet arrived.11 Slaveowners clamored to purchase slaves, in part because they knew the transatlantic slave trade to British ports would soon end, but if they expected healthy people who could be put to work right away, they were sorely disappointed. The captives before them “were such a set of scarcely animated automata, such a resurrection of skin and bone . . . they all looked so like corpses just arisen from the grave.”12

Less immediately visible than their physical suffering, but no less important, was the intense emotional trauma the captives faced during this new phase of their harrowing forced migration. The day they were sold may have been one “of feasting and hilarity” for colonials, as one British traveler observed, but “to the poor Africans it was a period of heavy grief and affliction.” They had been separated from friends and family by death and sale at every stage of their journey—from capture and enslavement in the Windward Coast interior to the march to the coast and ultimately the Middle Passage across the Atlantic. Strangers who had become shipmates would now “be sold as beasts of burden—torn from each other—and widely dispersed about the colony, to wear out their days in the hopeless toils of slavery.”13

What did the captives from the Barbados Packet make of their arrival in Berbice? The sights and sounds must have been overwhelming as they made their way from ship to shore, surrounded by merchants and hucksters, stevedores and planters, slaves and soldiers. What was it like to be “examin[ed] . . . limb after limb, . . . just as the dealers do with horses in our fairs in England?”14 As buyers and sellers haggled, captives would have heard a jumble of languages—Dutch and English, the local creole known as Berbice Dutch, and, from other newcomers, a variety of Central and West African languages, including Kikongo, Twi, and Igbo.15 As they followed their new owners to the plantations, houses, and workshops where they would soon be put to unfamiliar tasks—picking coffee, ginning cotton, grinding sugarcane, and preparing European foods—they may have searched the faces and bodies of other enslaved people for signs of home. The “country marks” some Africans bore may have helped them identify people from their homeland or neighboring West African societies—people who might answer their questions, or offer advice and solace.16 Captives from the Windward Coast were relatively rare, though, in Berbice, and the Barbados Packet captives would have seen many more strangers from Central Africa, the Bights of Benin and Biafra, and the Gold Coast than people who spoke their language and shared their culture. Other sights—slaves working in chains, white men cracking whips and barking orders—would have confirmed that the horrors they had become familiar with at sea would follow them on land. Many captives would soon die, unable to endure the “seasoning” or adjustment period to the West Indian environment, but those who survived would never forget the shipmates who endured the journey with them.17

As the Barbados Packet captives struggled to adapt and learn how to survive the plantation world, the future of West Indian slavery itself was increasingly uncertain. To be sure, planters were eager to build on the dramatic recent growth of slavery in Berbice and its neighbors, but they faced a number of obstacles. Berbice had been established in the seventeenth century by the Dutch, but was captured by the British in 1796, along with neighboring Demerara and Essequibo. For a short time, Britain’s new Guiana colonies were at the center of an expanding British slave system in the southern Caribbean after the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804).18 Between British occupation and the close of the transatlantic slave trade to the British colonies in 1808, a major blow to planters, some 270 voyages delivered at least 70,000 captives to British Guiana.19 Thousands more arrived from older West Indian colonies over the next four years, not counting those smuggled in.20 These enslaved laborers, combined with massive investment of British capital and the region’s famously fertile soil, were making Britain’s Guiana colonies the most productive and important slave societies in the West Indies. At the height of expansion, however, they were beset by a series of economic crises and imperial experiments in “amelioration” that threatened to bankrupt planters and destroy colonial slavery.21 Nineteenth-century Berbice was thus the site of two intersecting battles, as planters, lawmakers, and reformers fought to determine the fate of slavery and the plantation system. Meanwhile, enslaved Africans and their descendants struggled to make viable lives under desperate conditions. Ultimatel...