![]()

Part I

Clinical Aspects

of Depression

![]()

Chapter 1

The Definition of Depression

Paradoxes of Depression

Depression may someday be understood in terms of its paradoxes. There is, for instance, an astonishing contrast between the depressed person’s image of him- or herself and the objective facts. A wealthy woman moans that she doesn’t have the financial resources to feed her children. A widely acclaimed movie star begs for plastic surgery in the belief that he is ugly. An eminent physicist berates herself “for being stupid.”

Despite the torment experienced as the result of these self-debasing ideas, the patients are not readily swayed by objective evidence or by logical demonstration of the unreasonable nature of these ideas. Moreover, they often perform acts that seem to enhance their suffering. The wealthy man puts on rags and publicly humiliates himself by begging for money to support himself and his family. A clergyman with an unimpeachable reputation tries to hang himself because “I’m the world’s worst sinner.” A scientist whose work has been confirmed by numerous independent investigators publicly “confesses” that her discoveries were a hoax.

Attitudes and behaviors such as these are particularly puzzling—on the surface, at least—because they seem to contradict some of the most strongly established axioms of human nature. According to the “pleasure principle,” patients should be seeking to maximize satisfactions and minimize pain. According to the time-honored concept of the instinct of self-preservation, they should be attempting to prolong life rather than terminate it.

Although depression (or melancholia) has been recognized as a clinical syndrome for over 2,000 years, as yet no completely satisfactory explanation of its puzzling and paradoxical features has been found. There are still major unresolved issues regarding its nature, its classification, and its etiology. Among these are the following:

1. Is depression an exaggeration of a mood experienced by the normal, or is it qualitatively as well as quantitatively different from a normal mood?

2. What are the causes, defining characteristics, outcomes, and effective treatments of depression?

3. Is depression a type of reaction (Meyerian concept), or is it a disease (Kraepelinian concept)?

4. Is depression caused primarily by psychological stress and conflict, or is it related primarily to a biological derangement?

There are no universally accepted answers to these questions. In fact, there is sharp disagreement among clinicians and investigators who have written about depression. There is considerable controversy regarding the classification of depression, and a few writers see no justification for using this nosological category at all. The nature and etiology of depression are subject to even more sharply divided opinion. Some authorities contend that depression is primarily a psychogenic disorder; others maintain just as firmly that it is caused by organic factors. A third group supports the concept of two different types of depression: a psychogenic type and an organic type.

Prevalence of Depression

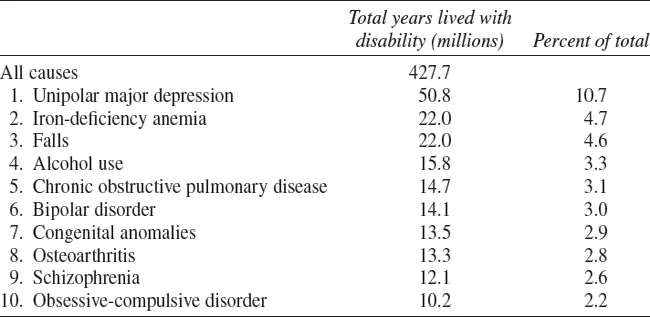

The importance of depression is recognized by everyone in the field of mental health. According to Kline,1 more human suffering has resulted from depression than from any other single disease affecting humankind. Depression is second only to schizophrenia in first and second admissions to mental hospitals in the United States, and it has been estimated that the prevalence of depression outside hospitals is five times greater than that of schizophrenia.2 Worldwide, Murray and Lopez3 found unipolar major depression to be the leading cause of disability in 1990, measured in years lived with a disability. Unipolar depression accounted for more than one in every ten years of life lived with a disability.

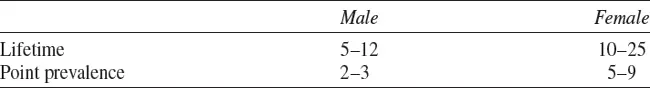

More than 40 years ago, a systematic survey of the prevalence of depression in a sharply defined geographical area indicated that 3.9 percent of the population more than 20 years of age were suffering from depression at a specified time.4 According to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) of the American Psychiatric Association,5 the probability during one’s lifetime of developing a major depressive disorder is 5–12 percent for males and 10–25 percent for females. At any given point in time (“point prevalence”), 2–3 percent of the male and 5–9 percent of the female population suffer from a major depression. Piccinelli6 reviewed the studies on gender differences in depression and found that the gender differences began at mid-puberty and continued through adult life.

TABLE 1-1. Leading Causes of Disability Worldwide, 1990

Adapted from Lopez and Murray 1998. For up-to-date WHO data, see http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/definition/en/

TABLE 1-2. Prevalence of Major Depressive Disorder by Gender (%)

Adapted from DSM-IV-TR.

Prevalence and Severity by Types and Age at Onset

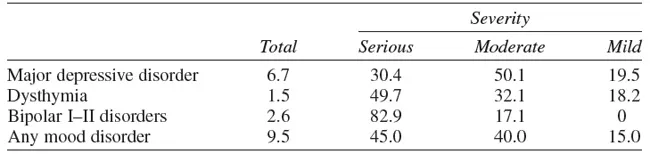

Lifetime prevalence rates for the other mood disorders (see Chapter 4 for distinctions among types) are reported in DSM-IV5 as follows: Dysthymic disorder 6 percent; Bipolar I 0.4–1.6 percent; Bipolar II 0.5 percent; Cyclothymic 0.4–1.0 percent. The National Institute of Mental Health (USA)7 reports that 18.8 million American adults (9.5 percent of the population age 18 or older) in a given year suffer from some form of depressive disorder. Major depressive disorder is the leading cause of disability in the established market economies around the world.7

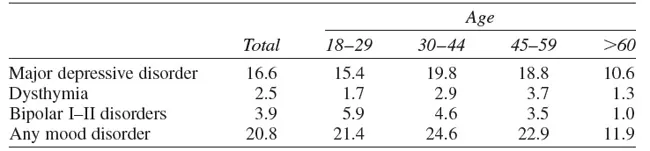

Twelve-month prevalence and severity rates are provided by Kessler et al.8 The U.S. National Comorbidity Survey Replication included a nationally representative face-to-face household survey conducted between February 2001 and April 2003. The study employed a structured diagnostic interview, the World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Initiative version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Participants included 9,282 English-speaking respondents 18 years and older. Twelve-month prevalence and estimates of mood disorders from this study are included in Table 1-3.

TABLE 1-3. Twelve-Month Prevalence and Severity of Mood Disorders (%)

Adapted from Kessler et al. 2005.

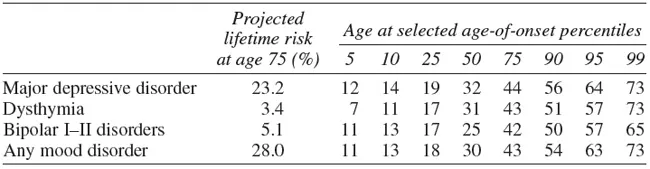

TABLE 1-4. Ages at Selected Percentiles on Standardized Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV/ WMH-CIDI Mood Disorders, with Projected Lifetime Risk at Age 75 Years

Adapted from Kessler et al. 2005.

TABLE 1-5. Lifetime Prevalence (%) of Disorders by Age

Adapted from Kessler et al. 2005.

Age of onset and lifetime prevalence rates (the likelihood of experiencing a mood disorder at some time in one’s lifetime) are presented in Tables 1-4 and 1-5.9

Descriptive Concepts of Depression

The condition that today we label depression has been described by a number of ancient writers under the classification of “melancholia.” The first clinical description of melancholia was made by Hippocrates in the fourth century B.C. He also referred to swings similar to mania and depression.10

Aretaeus, a physician living in the second century A.D., described the melancholic patient as “sad, dismayed, sleepless. . . . They become thin by their agitation and loss of refreshing sleep. . . . At a more advanced stage, they complain of a thousand futilities and desire death.” It is noteworthy that Aretaeus specifically delineated the manic-depressive cycle. Some authorities believe that he anticipated the Kraepelinian synthesis of manic-depressive psychosis, but Jelliffe discounts this hypothesis.

Plutarch, in the second century A.D., presented a particularly vivid and detailed account of melancholia:

He looks on himself as a man whom the Gods hate and pursue with their anger. A far worse lot is before him; he dares not employ any means of averting or of remedying the evil, lest he be found fighting against the gods. The physician, the consoling friend, are driven away. ‘Leave me,’ says the wretched man, ‘me, the impious, the accursed, hated of the gods, to suffer my punishment.’ He sits out of doors, wrapped in sackcloth or in filthy rags. Ever and anon he rolls himself, naked, in the dirt confessing about this and that sin. He has eaten or drunk something wrong. He has gone some way or other which the Divine Being did not approve of. The festivals in honor of the gods give no pleasure to him but fill him rather with fear or a fright. (quoted in Zilboorg11)

Pinel at the beginning of the nineteenth century described melancholia as follows:

The symptoms generally comprehended by the term melancholia are taciturnity, a thoughtful pensive air, gloomy suspicions, and a love of solitude. Those traits, indeed, appear to distinguish the characters of some men otherwise in good health, and frequently in prosperous circumstances. Nothing, however, can be more hideous than the figure of a melancholic brooding over his imaginary misfortunes. If moreover possessed of power, and endowed with a perverse disposition and a sanguinary heart, the image is rendered still more repulsive.

These accounts bear a striking similarity to modern textbook descriptions of depression; they are also similar to contemporary autobiographical accounts such as that by Clifford W. Beers.12 The cardinal signs and symptoms used today in diagnosing depression are found in the ancient descriptions: disturbed mood (sad, dismayed, futile); self-castigations (“the accursed, hatred of the gods”); self-debasing behavior (“wrapped in sackcloth or dirty rags . . . he rolls himself, naked, in the dirt”); wish to die; physical and vegetative symptoms (agitation, loss of appetite and weight, sleeplessness); and delusions of having committed unpardonable sins.

The foregoing descriptions of depression include the typical characteristics of this condition. There are few psychiatric syndromes whose clinical descriptions are so constant through successive eras of history (For descriptions of depression through the ages, see Burton.13) It is noteworthy that the historical descriptions of depression indicate that its manifestations are observable in all aspects of behavior, including the traditional psychological divisions of affection, cognition, and conation.

Because the disturbed feelings are generally a striking feature of depression, it has become customary to regard this condition as a “primary mood disorder” or as an “affective disorder.” The central importance ascribed to the feeling component of depression is exemplified by the practice of utilizing affective adjective checklists to define and measure depression. The representation of depression as an affective disorder is as misleading as it would be to designate scarlet fever as a “disorder of the skin” or as a “primary febrile disorder.” There are many components of depression other than mood deviation. In a significant proportion of the cases, no mood abnormality at all is elicited from the patient. In our present state of knowledge, we do not know which component of the clinical picture of depression is primary, or whether they are all simply external manifestations of some unknown pathological process.

Depression may now be defined in...