![]()

Chapter One

THE PORTFOLIOS

OF THE POOR

PUBLIC AWARENESS of global inequality has been heightened by outraged citizens’ groups, journalists, politicians, international organizations, and pop stars. Newspapers report regularly on trends in worldwide poverty rates and on global campaigns aimed at halving those rates. A daily income of less than two dollars per person has become a widely recognized benchmark for defining the world’s poor. The World Bank counted 2.6 billion people in this category in 2005—two-fifths of humanity. Among these 2.6 billion, the poorest 0.9 billion were scraping by on less than one dollar a day.

For those of us who don’t have to do it, it is hard to imagine what it is like to live on so small an income. We don’t even try to imagine. We suppose that with incomes at these impossibly low levels, the poor can do little for themselves beyond hand-to-mouth survival. Their chances of moving out of poverty must depend, we assume, either on international charity or on their eventual incorporation into the globalized economy. The hottest public debates in world poverty, therefore, are those about aid flows and debt forgiveness, and about the virtues and vices of globalization.1 Discussion of what the poor might do for themselves is less often heard. If it’s hard to imagine how you would survive on a dollar or two a day, it’s even harder to imagine how you would prosper.

Suppose that your household income indeed averaged two dollars or less a day per head. If you’re like others in that situation, then you’re almost surely casually or part-time or self-employed in the informal economy. One of the least remarked-on problems of living on two dollars a day is that you don’t literally get that amount each day. The two dollars a day is just an average over time. You make more on some days, less on others, and often get no income at all. Moreover, the state offers limited help, and, when it does, the quality of assistance is apt to be low. Your greatest source of support is your family and community, though you’ll most often have to rely on your own devices.

Most of your money is spent on the basics, above all food. But then how do you budget? How do you make sure there is something to eat and drink every day, and not just on the days you earn? If that seems hard enough, how do you deal with emergencies? How can you be sure that you can pay for the doctor and the drugs your children need when they fall sick? Even without emergencies, how do you put together the funds you need to afford the big-ticket items that lie ahead—a home and furniture, education and marriage for your children, and some income for yourself when you’re too old to work? In short, how do you manage your money if there is so little of it?

These are practical questions that confront billions every day. They are also starting points for imagining new ways for businesses to build markets that serve those living on one or two or three dollars per day. They are obvious starting points as well for policymakers and governments seeking to confront persistent inequalities.

Though these questions about the financial practices of the poor are fundamental, they are surprisingly hard to answer. Existing data sources offer limited insights. Neither large, nationally representative economic surveys of the sort employed by governments and institutions like the World Bank, nor small-scale anthropological studies or specialized market surveys, are designed to get at these questions. Large surveys give snapshots of living conditions. They help analysts count the number of poor people worldwide and measure what they typically consume during a year. But they offer limited insight into how the poor actually live their lives week by week—how they create strategies, weigh trade-offs, and seize opportunities. Anthropological studies and market surveys examine behavior more closely, but they seldom provide quantified evidence of tightly defined economic behavior over time.

Given this gap in our knowledge and our own accumulating questions, several years ago we launched a series of detailed, yearlong studies to shed light on how families live on so little. Some of the studies followed villagers in agricultural communities; others centered on city-dwellers. The first finding was the most fundamental: no matter where we looked, we found that most of the households, even those living on less than one dollar a day per person, rarely consume every penny of income as soon as it is earned. They seek, instead, to “manage” their money by saving when they can and borrowing when they need to. They don’t always succeed, but over time, even for the poorest households, a surprisingly large proportion of income gets managed in this way—diverted into savings or used to pay down loans. In the process, a host of different methods are pressed into use: storing savings at home, with others, and with banking institutions; joining savings clubs, savings-and-loan clubs, and insurance clubs; and borrowing from neighbors, relatives, employers, moneylenders, or financial institutions. At any one time, the average poor household has a fistful of financial relationships on the go.

As we watched all this unfold, we were struck by two thoughts that changed our perspective on world poverty, and on the potential for markets to respond to the needs of poor households. First, we came to see that money management is, for the poor, a fundamental and well-understood part of everyday life. It is a key factor in determining the level of success that poor households enjoy in improving their own lives. Managing money well is not necessarily more important than being healthy or well educated or wealthy, but it is often fundamental to achieving those broader aims. Second, we saw that at almost every turn poor households are frustrated by the poor quality—above all the low reliability—of the instruments that they use to manage their meager incomes. This made us realize that if poor households enjoyed assured access to a handful of better financial tools, their chances of improving their lives would surely be much higher.

The tools we are talking about are those used for managing money—financial tools. They are the tools needed to make two dollars a day per person not only put food on the dinner table, but cover all the other spending needs that life puts in our way. The importance of reliable financial tools runs against common assumptions about the lives and priorities of poor families. It requires that we rethink our ideas about banks and banking. Some of that rethinking has already started through the global “microfinance” movement, but there is further to travel. The findings revealed in this book point to new opportunities for philanthropists and governments seeking to create social and economic change, and for businesses seeking to expand markets.

The poor are as diverse a group of citizens as any other, but the one thing they have in common, the thing that defines them as poor, is that they don’t have much money. If you’re poor, managing your money well is absolutely central to your life—perhaps more so than for any other group.

Financial Diaries

To discover the crucial importance of financial tools for poor people, we had to spend time with them, learning about their money-management methods in minute detail. We did so by devising a research technique we call “financial diaries.” In three countries, first in Bangladesh and India and a little later in South Africa, we interviewed poor households, at least twice a month for a full year, and used the data to construct “diaries” of what they did with their money. Altogether we collected more than 250 completed diaries.2 Over time the answers to our questions about how poor households manage money started to add up and reinforce each other—and, importantly, they meshed with what we had seen and heard over the years in our work in other contexts: in Latin America and elsewhere in Africa and Asia.3

We learned how and when income flowed in and how and when it was spent. Looking at poor households almost as one might look at a small business, we created household-level balance sheets and cash-flow statements, focusing our lens most sharply on their financial behavior—on the money they borrowed and repaid, lent and recovered, and saved and withdrew, along with the costs of so doing. Our understanding of these choices was enriched by the real-time commentary of the householders themselves. We listened to what they had to say about their financial lives: why they did what they did, what was hard and what was easy, and how successful they felt they had been. It was, surprisingly, the tools of corporate finance—balance sheets and cash-flow statements—that offered the structure with which we could begin to understand what it takes, day by day, for poor households to live on so little.4

To get a first sense of what the financial diaries reveal, consider Hamid and Khadeja. The couple married in a poor coastal village of Bangladesh where there was very little work for a poorly educated and unskilled young man like Hamid. Soon after their first child was born they gave up rural life and moved, as so many hundreds of thousands had done before them, to the capital city, Dhaka, where they settled in a slum. After spells as a cycle-rickshaw driver and construction laborer and many days of unemployment, Hamid, whose health was not good, finally got taken on as a reserve driver of a motorized rickshaw. That’s what he was doing when we first met Hamid and Khadeja in late 1999, while Khadeja stayed home to run the household, raise their child, and earn a little from taking in sewing work. Home was one of a strip of small rooms with cement block walls and a tin roof, built by their landlord on illegally occupied land, with a toilet and kitchen space shared by the eight families that lived there.

In an average month they lived on the equivalent of $70, almost all of it earned by Hamid, whose income arrived in unpredictable daily amounts that varied according to whether he got work that day (he was only the reserve driver) and, if he did get work, how much business he attracted, how many hours he was allowed to keep his vehicle, and how often it broke down. A fifth of the $70 was spent on rent (not always paid on time), and much of the rest went toward the most basic necessities of life—food and the means to prepare it. By the couple’s own reckoning, which our evidence agrees with, their income put them among the poor of Bangladesh, though not among the very poorest. By global standards they would fall into the bottom two-fifths of the world’s income distribution tables.

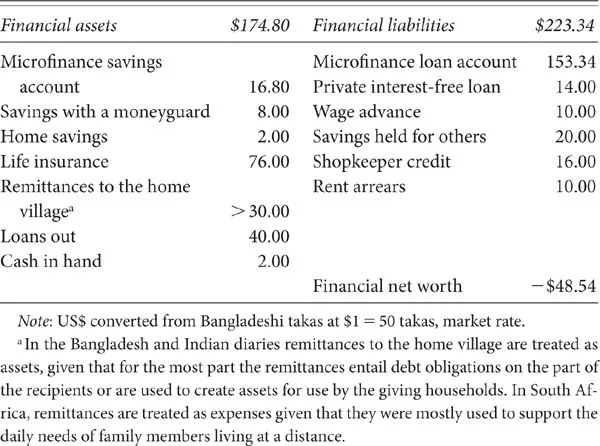

An unremarkable poor household: a partly educated couple trying to stay alive, bring up a child, run a one-room home, and keep Hamid’s health in shape—on an uncertain $0.78 per person per day. You wouldn’t expect them to have much of a financial life. Yet the diversity of instruments in their year-end household balance sheet (table 1.2) shows that Hamid and Khadeja, as part of their struggle to survive within their slim means, were active money managers.

Far from living hand-to-mouth, consuming every taka as soon as it arrived, Hamid and Khadeja had built up reserves in six different instruments, ranging from $2 kept at home for minor day-to-day shortfalls to $30 sent for safe-keeping to his parents, $40 lent out to a relative, and $76 in a life insurance savings policy. In addition, Hamid always made sure he had $2 in his pocket to deal with anything that might befall him on the road.

Table 1.2 Hamid and Khadeja’s Closing Balance Sheet, November 2000

Their active engagement in financial intermediation also shows up clearly on the liabilities side of their balance sheet. T...