![]()

1

INTRODUCTION: “UNMASKED AT LAST!”

Death, Disability, and the Super-Body

As it oscillates between being a thing and my being, as it undergoes and yet disengages itself from reification, my body responds with a language that is as commonplace as it is startling. For the body is not only this organic mosaic of biological entities. It is also a cornucopia of highly charged symbols—fluids, scents, tissues, different surfaces, movements, feelings, cycles of changes constituting birth, growing old, sleeping and waking. Above all, it is with disease with its terrifying phantoms of despair and hope that my body becomes ripe as little else for encoding that which society holds to be real—only to impugn that reality. (Taussig: 86)

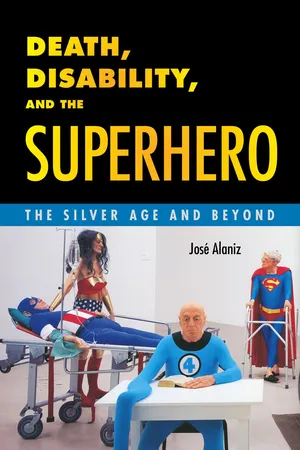

The French artist Gilles Barbier’s installation Nursing Home (2002) features a sextet of wax figures: aged superheroes slumped over, gurneyed, or otherwise sprawled before a television set declaiming advertisements. A bald Mister Fantastic of the Fantastic Four sits at a table, staring dumbly into space, his flaccid limbs twisted and warped in impossible contortions. A shriveled Hulk, still in tattered purple pants, dozes in a wheelchair. White-haired Superman leans stoically on a walker.

Nursing Home comprised part—judging by press accounts, the most crowd-pleasing part—of the New York Whitney Museum of American Art’s 2003 exhibition, “The American Effect: Global Perspectives on the United States, 1990–2003,” which surveyed several international artists’ responses to post-9/11 US hegemony.

The geriatric do-gooders proved a hit; while some, like Peter Schjeldahl in his New Yorker review, dismissed Barbier’s work as “no-rate art” (82) derivative of Edward Keinholz, and faulted the entire exhibit for its “soft core” reproach of American cultural imperialism, most critics responded along the lines of Mark Stevens of New York magazine: “As a work of art, Nursing Home is essentially a one-liner—the punch line about America could hardly be more obvious—but it’s also very funny.” Similarly, Georgette Gouveia of New York’s Journal News opined: “In one sense, it’s an affectionate homage . . . to the comic-book hero as a staple of American creativity. In another sense, however, the installation can be viewed as a critique of our youth-obsessed culture, with its underlying fear of death.”

Critically, Barbier’s piece marks—in fact, banks on—the “viewer-friendly” appeal of superhero iconography as shorthand not only for American popular culture, but for American values and their global perception as velvet-gloved fascism as well. The fact that Nursing Home is the work of a foreigner drives home this point; many gallery visitors who have never read a Fantastic Four or Captain America comic book (and who in fact may not have access to such titles in their home countries) nonetheless immediately grasp Barbier’s symbolism: “Superhero = America.”1

The “super signifier” of the super-body thus reifies nation, death-denying vigor, and sexual potency. This makes Nursing Home a lacerating parody; Barbier reintroduces time, the one element inimical to myth, of whatever ideological stripe. He fuses the “flash” of fantastic superheroics and the can-do American optimism it incarnates with the deflating reality principle of the exhausted, decrepit, dying body. (Wonder Woman, Superman, and Captain America are all represented at something like the age they would be, given the actual number of years since their first appearance in the comics.) Nursing Home thereby equates the disabled bodies of the elderly heroes with the flawed, discredited, and obsolete American Dream.

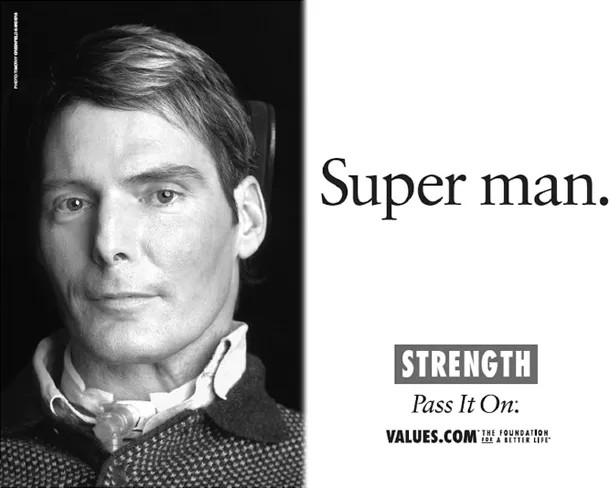

Barbier’s piece, of course, only enacts a reversal of conventional American pop iconography in a bid to overcome the high-low divide. Rather than turn the body “against” the icon, as Barbier does (and as a 2004 French public AIDS awareness campaign using emaciated superheroes also did),2 much mainstream visual culture uses the superhero signifier to “enhance” the body to an imagined ideal—thereby displacing the disabled, dying or dead body. Indeed, no sooner had the “American Effect” exhibit closed and the ailing heroes of Nursing Home moved on than the Foundation for a Better Life unveiled a 2003 nationwide billboard campaign featuring Christopher Reeve. Star of the Superman movies of the 1970s and 1980s, Reeve suffered a paralyzing accident in 1995 and had since used his celebrity to advocate for spinal cord injury causes. Next to a head portrait of Reeve (which avoids showing his body below the neck), the billboard declares: “Super man/Strength/Pass It On.”

The public service message advanced Reeve’s image as a former Superman who publicly and insistently declared his intention to “beat” his quadriplegia and walk again—which he “did” through the magic of computer-generated effects in a notable 2000 Super Bowl ad for Nuveen Investments. The late Reeve’s stance earned him the wrath of many in the disabled community, who deemed him a grandstanding celebrity misrepresenting the lived reality of others in his situation (who had only a fraction of his resources).3 Seen by millions on the American advertising industry’s biggest day, the TV ad sparked a minor hysteria in some quarters over rumors that an able-bodied Reeve really had walked.4 This, despite some rather obvious anatomical shortcomings in the ad, as noted by a critical Charles A. Riley: “It featured a ludicrously fake shot of a man walking with Reeve’s head barely affixed digitally to his shoulders (the creators seemed to have forgotten the neck part, and the head was far too small for the proportions of the body)” (127). Such was the imagistic power of the super-body to tap into popular desires for a “cure.”

1.1 The Foundation for a Better Life’s public service ad featuring Christopher Reeve, 2003.

No surprise, given its decades-long iconography (dismissed, disavowed, derogated, but casually embraced) of hyper-masculinized vigor.5 As discussed throughout this book, the superhero makes an alluring figure both for the reimagining/representation of (national, sexual, psychosocial) selves and for a critique of the rhetorical/tropological modes that frame them. More particularly, as shown by the works examined within these pages, the superhero serves as an entry point for interrogating the social construction of the (male) body, disability, death, illness, and “normality” in postwar American popular culture.6 My reading hinges on an interpretation of the super-body as a site of elaborate, overdetermined signification. As a means of arriving at that reading, the next section briefly considers the history, ideological uses and popular perceptions of the superhero from its origins, through the Silver Age and beyond.

THE SUPERHERO

Since its inauguration in 1938’s Action Comics #1, the superhero genre—as reflected all too graphically and for various purposes in Barbier’s Nursing Home, the Nuveen ad, and their aftermath—has served as a disability and death-denying representational practice which privileges the healthy, hyper-powered, and immortal body over the diseased, debilitated and defunct body. The superhero, by the very logic of the narrative, through his very presence, enacts an erasure of the normal, mortal flesh in favor of a quasi-fascist physical ideal.

Canonical Golden Age heroes such as Superman (Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, 1938), Batman (Bob Kane and Bill Finger, 1939), Wonder Woman (William Moulton Marston, 1941), and Captain America (Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, 1941), no less than more obscure figures such as The Comet (Jack Cole, 1940), Stardust (Fletcher Hanks, 1940), The Flame (Will Eisner and Lou Fine, 1939), Phantom Lady (Eisner & Iger studio, 1941), and Dr. Mystic (Siegel and Shuster, 1936) all advance that corporeal archetype, flourishing fully equipped (white) bodies “ready for anything.” Chief among its corporeal features: strength, control, unboundedness—an utter disavowal of fleshly fragility. As noted by Scott Bukatman, “The superhero body is a body in a permanent state of readiness (this is a job for . . .). What’s more, if random death now appears from nowhere, the superbody is more than merely resistant; it bears its own mysterious power” (Bukatman 2003: 53, italics in original).

Scholars like Bukatman have linked such weighted imagery to the comics’ primary audience, adolescent boys, and in particular to their presumed power fantasies, need for substitute father figures, and will to domination.7 Others emphasize the nationalistic aspects of superheroes as part of American “fake-lore,” traced to the heroic figures of the oral epics going back to the founding of the country, if not before. Similarly, some point to the superhero’s evocation of nostalgia for an idealized past or personal childhood (the baggage such evocations often bear). The more psychoanalytical approaches mine superheroes for their often paradoxical messages about gender, denial, sexuality, fashion, modern anxieties, desire, and the split self. Still others see the superhero genre as a marginalized, much-maligned twentieth-century artistic and/or literary form only recently subjected to critical and popular reassessment, with a concomitant admission to college syllabi.8

This list of the superhero’s “uses”—which one could lengthen substantially—demonstrates the genre’s appeal (popular, sociocultural, political), its flexible expediency for various ends. An inviting mode of representation, a “costume” easily appropriated and donned, the superhero in recent years has indeed received unprecedented (and long overdue) attention from scholars.

Books on the subject include the landmark Superheroes: A Modern Mythology, by Richard Reynolds (1992), built on earlier historical treatments such as The Comic Book Heroes: From the Silver Age to the Present, by Will Jacobs and Gerard Jones (1985); Arthur Asa Berger and M. Thomas Inge’s attention to the cultural significance of the genre in the 1970s and 1980s, followed by such works as The Many Lives of the Batman, edited by Roberta A. Pearson and William Uricchio (1991); How to Read Superhero Comics and Why, by Geoff Klock (2003); Superman on the Couch: What Superheroes Really Tell Us About Ourselves and Our Society, by Danny Fingeroth (2004); Superhero: The Secret Origin of a Genre, by Peter Coogan (2006); Batman and Philosophy: The Dark Knight of the Soul, edited by Robert Arp and Mark D. White; Grant Morrison: Combining the Worlds of Contemporary Comics, by Marc Singer (2011); Do the Gods Wear Capes?: Spirituality, Fantasy and Superheroes, by Ben Saunders (2011); and Hand of Fire: The Narrative Art of Jack Kirby, by Charles Hatfield (2012).9

All these works, including the present study, owe a tremendous debt to the pioneering investigations of an earlier generation of scholars and popular historians which addressed superhero comics, at times in the face of institutional resistance, which includes Coulton Waugh, Roland Barthes, Umberto Eco, and Marshall McLuhan; the excursus which unfolds over the next few pages draws liberally and unavoidably on their insights.10

More recently, superheroes themselves have seen a steady expansion into literature, as evinced by novels such as Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay (2000); Soon I Will Be Invincible, by Arthur Grossman (2007); Karma Girl, by Jennifer Estep (2007), as well as works by Jonathan Lethem. In the 2000s, they also made major inroads into video games, television, film (Smallville, Heroes, The Cape, the Spider-Man, Hulk, Iron Man, Fantastic Four, and the Batman franchises, and even, arguably, The Matrix series), art (with Barbier being only one example) and American popular culture, of which they form a long-standing and indelible facet. We may remember the late twentieth/early twenty-first century, in fact, as the Age of the Multimedia Superhero, when—thanks largely to advances in special effects technology—the genre achieved near-ubiquity among the public, acclaim (or at least acceptance) from critics, and major box-office clout.

All this makes plain that superheroes—despite (or indeed because of) their seeming simplicity—serve as tantalizing palimpsests for thinking through many aspects of past and contemporary American life, while their seven-decade publishing record has produced a daunting accumulation of narratival complexity (not the least of which is their innumerable stylistic variations), especially for the most successful characters. As Bukatman puts it, “At first glance they are terribly crude—especially in their first decades of existence—but familiarity and developing history endow them with copious nuance” (2003: 184).

Launched by two Clevelanders barely out of their teens on the eve of World War II—and since made available for myriad ideological and cultural purposes (both utopian and dystopian)—the superhero genre represents (in its own parlance) a rich “mirror universe” of American society. Or, in the words of Douglas Wolk: “Superhero comics are, by their nature, larger than life, and what’s useful and interesting about their characters is that they provide bold metaphors for discussing ideas or reifying abstractions into narrative fiction” (2007: 92).

Proceeding from Coogan’s taxonomical treatment of the superhero11 as resting primarily on four major pillars—mission, powers, (secret) identity and genre distinction (58)—and his deployment of a Wittgensteinian “family resemblances” or “constellation of conventions” model (40) to ground his definition (which privileges potentiality and an informed ecumenism over tiresome checklists for what does and does not “count” as a superhero),12 let us examine the major features of the genre with an eye to how they inform the present study.

THE SUPERHERO, IDEOLOGY, AND MYTH

Firstly, Barbier’s pointed critique of superheroes as stand-ins for America resonates with earlier treatments of these figures as quintessentially national symbols. Proceeding from the folklorist Joseph Campbell’s Jungian-inflected reading of the hero myth across cultures (i.e., monomyth),13 along with the historian Richard Slotkin’s emphasis on “regenerative violence” and the national imaginary, Robert Jewett and John Shelton Lawrence argue for the ultimately religious roots of this most American of genres:

Whereas the classical monomyth seemed to reflect ...