![]()

CHAPTER 1

From Sustainability to Flourishing

Why are so many executives struggling with corporate sustainability? To answer this question, a fresh outlook is needed. We start by recognizing that what is usually projected under the heading of sustainability has, by any measure, become insufficient for either business or society. Sustainability-related practices have implicitly focused, whether intentionally or not, on what business can do to mitigate harm or avoid disaster. In other words, the primary attention has been on being less bad. Imagine for a moment that the physicians’ Hippocratic Oath was to hurt the patient less rather than to do no harm. We’d be in a world of hurt! Yet corporate sustainability initiatives such as cutting greenhouse gases or reducing waste only help a business be “less unsustainable.” Few initiatives today are designed with solutions to global challenges in mind, and fewer still fulfill the systemic conditions for a healthy world over the long term.

Even the growing social entrepreneurship movement, which aims to provide innovative solutions to global sustainability challenges, is having limited success in making a world-changing impact. Although motivated by social rather than economic gain, this movement is challenged to find ways to scale impact, in part because of the inherent growth limitations linked to capital funding in small organizations that are heavily dependent on a founder’s vision for success.

What if, instead of aiming primarily at reducing their footprint, businesses adopted a different way of thinking: what if, rather than only reducing their negative impacts, they started to think in terms of having a positive handprint, which Australian activist Kathryn Bottrell defines as “a mark and measure of making a positive contribution in the world?1” What would this look like?

The Tata Group, an Indian conglomerate founded in 1868 with current sales of $100 billion, is one among a growing number of examples that exist today. This company puts making a positive contribution at the core of its reason for being. Its corporate purpose of “improving the quality of life of the communities we serve” and “returning to society what we earn” forms the basis of its business conduct. Karambir Singh Kang, an executive at Taj Hotels, a division of the Tata Group, says this about his company: “You will not find the names of our leaders among the names of the richest people in the world. We have no one on the Forbes list. Our leaders are not in it for themselves; they are in it for society, for the communities they serve.”2 For some observers the paradox of Tata’s way of doing business is the extraordinary results that come with it, most recently under its chairman, Ratan Tata, who transformed the group into a highly profitable global powerhouse over the past twenty years.3 Its portfolio of products now includes a $22 water purifier that works without electricity or the need for running water, designed to serve the nearly one billion people worldwide who lack access to clean water. As Wired Magazine put it, with such products “Tata is saving lives and making a killing.”4

Or consider Natura, the Brazilian natural cosmetics company with an innovative sales network of more than one million people, many of them poor residents of urban slums known as favelas. Chosen in 2011 by Forbes magazine as the eighth most innovative company in the world (in the company of Apple, which ranked fifth, and Google, which ranked seventh),5 Natura has always operated from a distinct and deeply felt sense of purpose. Its founder, Luiz Seabra, says, “At age 16, I was given this quote from Plotinus, a philosopher: ‘The one is in the whole; the whole is in the one.’ That was a revelation to me. This notion of being part of a whole has never left me.”6 Natura’s corporate purpose is concisely stated: Well-Being and Being Well. The company’s goal is to cultivate healthy, transparent, positive relationships—between the company and its stakeholders, among those stakeholders, and between them and the whole system of which they are a part. Although the firm is not widely known outside of South America, it provides a formidable example of a company that does well by doing good, with a recent net profit of $440 million on annual sales of more than $3 billion.

Why Today’s Sustainability Results Disappoint

Yet for all the success of companies like Tata and Natura, across a broad range of firms there is a surprising gap between executive talk about sustainability and the ability to actually create value from it. Data from a joint study conducted by the MIT Sloan Management Review and the Boston Consulting Group suggest that as early as 2011, two-thirds of all companies believed that sustainability was a source of competitive advantage.7 This awareness of sustainability as a driver of business value appears encouraging, but a more sobering statistic shows that only a third of the respondents actually reaped financial profits from efforts toward sustainability. A 2011 McKinsey global survey of 3,200 executives shows similar results, with 73 percent saying it is now a priority on their CEO agenda, but less than 15 percent of respondents citing return on capital levers over the next five years.8

Even though corporate sustainability initiatives are more widespread now than in previous years, they are often diluted or appear to be flagging. Many of the niche pioneers of the 1970s and 1980s have been absorbed by big players, as in the case of Ben & Jerry’s (Unilever) and The Body Shop (L’Oréal). Global corporations that promised to make sustainability a part of everything they did seem to have been unable to stay the course, either because of spectacular crises such as BP’s Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico or because of leadership changes and confusion about focus,9 leading to “sustainability fatigue.” Whether the fatigue is the result of the “bloom being off the rose,” a sense that attention to sustainability is “just one more thing on my overfull plate,” or a sense that it was, sadly, just another flavor of the month, the initial energy behind the movement seems to have dissipated, despite all the public statements about the importance of sustainability. We must tap into a different level of energy and a persistent commitment in order to reinvigorate corporate efforts.

A Shareholder Perspective

Our individual and collective work with executives across a wide range of companies led us to observe that sustainability initiatives have typically begun outside their core strategy and business planning processes, and having begun thus, it has later been difficult to make those initiatives part of the organizations’ core cultures, routines, and strategies. In tough economic times tangential efforts naturally fall by the wayside. But even in good times they suffer from being peripheral and from drawing only sporadic attention.

Organizations typically go through several phases in their sustainability efforts. First they identify activities they are already doing that can be couched in sustainability terms. They frame and communicate these efforts in corporate social responsibility (CSR) reports, at conferences, and in their press releases. They look for efforts that are newsworthy, even when many (such as a small solar installation at the entrance of an energy-intensive manufacturing facility) may not have significant impact overall.

Next, they begin tracking performance against key indicators and looking for ways to improve their sustainability performance. Here success typically comes in areas that are consistent with the company’s pre-existing culture and ways of operating. For example, Walmart had significant early success with cost-saving efforts, such as introducing innovations to improve the energy efficiency of its buildings and truck fleet and reducing the amount of packaging in its own-branded products.

However, sustainability efforts often run into trouble when they conflict with current ways of operating and require new levels of collaboration both within the organization and with outsiders (such as other industry players or value chain partners). Walmart faced significant challenges partnering with suppliers to bring more sustainable products to market. This is in part because the “buyer” culture (based on the company having massive purchasing power over its suppliers) favored price negotiation rather than innovative and long-term partnerships. In a 2011 interview published in the Wall Street Journal, the head of Walmart’s U.S. division responded to criticism that the company had “lost its way a bit” and was no longer as focused as it needed to be on offering the lowest possible prices. He reported that “sustainability and some of these other initiatives can be distracting.”10 While former CEO Lee Scott saw sustainability as a true paradigm shift for the company, this divisional executive’s words suggest that the established cultural norms and ways of doing things exert strong pressure to return to the status quo.

Given this tug of war between old and new, and the widespread but inaccurate assumption that by their very nature sustainability efforts take a long time to produce profits, shareholders seemed to have good reason to be disappointed. With investors disgruntled, why should management risk what could appear to be a weakly performing sustainability agenda?

A Stakeholder Perspective

When we turn to stakeholders—particularly the citizens and organizations who fight for social and environmental causes—the picture is even more disappointing. All meaningful indicators suggest that major systems across the world are becoming at best less unsustainable and at worst we are heading toward major crises. Progress toward the Millennium Development Goals is mixed.11 Poverty and the gap between the rich and the poor are growing, even in high-income countries; and progress toward improving maternal health and reducing child mortality is stalled in many parts of the world.

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), chronic hunger has been steadily rising since the mid-1990s and in 2012 affected 900 million people worldwide.12 Efforts to become more environmentally sustainable, as measured by reversing forest loss and reducing the proportion of the population without access to clean drinking water, are faltering in many regions. In climate-change terms, carbon dioxide emissions grew by 2.07 percent in 2013, increasing the total amount of atmospheric carbon to 400 parts per million.13 To provide historical perspective, atmospheric carbon stood at around 280 ppm for the last million years as measured by ice core samples. By 2013, atmospheric carbon had surpassed 400 ppm,14 a level that many see as putting us at risk for catastrophic climate change.15

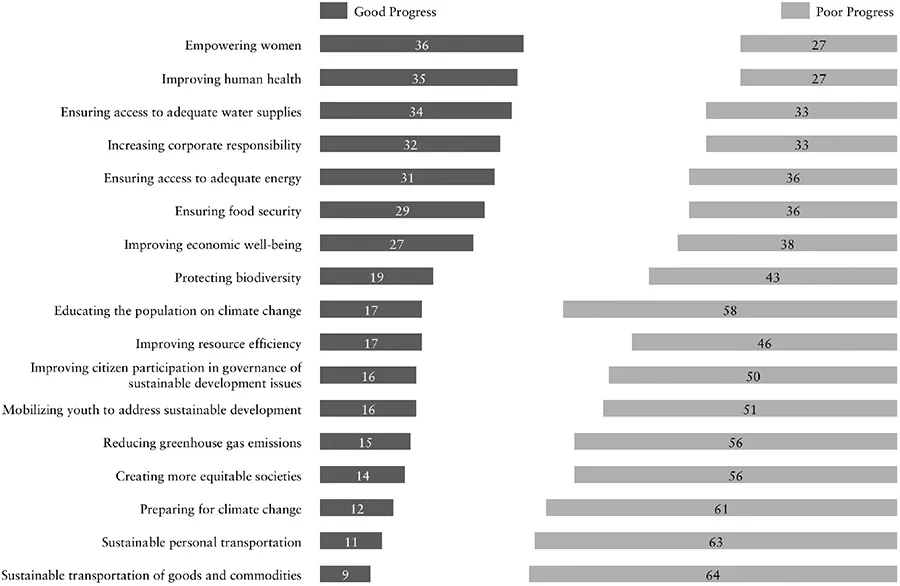

FIGURE 1.1 Global Expert Perspectives on the State of Sustainable Development

SOURCE: GlobeScan SustainAbility Survey of 1600 Sustainable Experts. Last accessed 09/23/2012.

In a 2012 survey conducted by SustainAbility and GlobeScan, 1,603 experts worldwide, drawn from corporate, government, nongovernmental, academic, media, and other organizations, responded to a series of questions regarding the progress of sustainable development (SD) in the past two decades.16 As Figure 1.1 shows, only three of seventeen indicators (empowering women, improving human health, and ensuring access to adequate water supplies) were perceived to have made slightly more “good progress” than “poor progress” over the past two decades. Several grievous problems, such as protecting biodiversity and creating more equitable societies, were estimated to have worsened significantly.

Poor progress is seen not only in terms of social equity. It also encompasses practical realities that businesses already care deeply about, such as improving resource efficiency and providing sustainable transportation of goods and commodities.

In light of these poor shareholder and stakeholder outcomes, to claim that business, as an institution, is materially contributing to a more sustainable world seems increasingly far-fetched. Could the idea of sustainability—the very term—be responsible for the poor results we observe? Are companies such as Tata and Natura, which are bucking these trends, actually doing something else? We argue that they are.

Book Tour by Chapter

Let us walk you through the territory ahead. Chapter 1 reframes sustainability as flourishing and outlines what we mean by the new spirit of business. Chapter 2 provides the historical context, including the external market forces and internal motives that are driving a spiritual dimension into all enterprise. It examines our increased collective desire for meaning and our rising awareness that business is not contri...