![]()

1

Subcarpathian Rus' Until World War I

A Culture Across Ethnic and Religious Boundaries

THE SEEDS OF THE HISTORICAL DYNAMICS that unfolded in Subcarpathian Rus' during the interwar years and World War II lay embedded in the pre–World War I era. What characterized the borderland society of Subcarpathian Rus' before it began to unravel? What roles and positions did Jews occupy? And what was typical of their relations with other groups in the region? The brutal years of World War I that brought this period to a close offer important insights that can help us to understand the later acute crisis that culminated in social disintegration and destruction of Jewish life. Most important, the ways in which external forces introduced violence into the area would continue to color the lives of Jews and non-Jews from one global war to the next.

The experience of estrangement in relation to external elements such as the Hungarian state figured prominently in the history of Jews in Subcarpathian Rus'. It also marked the history of the majority population, Carpatho-Ruthenians. Between them, however, these two groups found much common ground. The factors that accounted for such relations stand at the center of this chapter.

The Nineteenth Century

Jews had begun to settle in Subcarpathian Rus' in the middle of the seventeenth century, and a substantial Jewish presence developed in the first half of the nineteenth century.1 Between 1830 and 1880 the Jewish population in the region increased dramatically, in tandem with the rapid growth of the population as a whole.2 The flow of Galician Jewish immigrants into Subcarpathian Rus', prompted by the partitions of Poland at the end of the eighteenth century, led to the establishment and steady growth of new communities throughout the nineteenth century. The Yiddish-speaking, highly religious character of Galician Jews, particularly Hasidism, thus became a dominant feature of Jewish life in Subcarpathian Rus'.

In most cases local magnates encouraged Jewish settlement. The Schönborn family invited the first Jews to Munkács (Mukachevo), which would become the center of Jewish life in the region. In 1741 these Jews established the first synagogue for their community of around eighty people.3 By the beginning of the twentieth century, nine more synagogues served more than sixty-five hundred souls.4 On the eve of World War I Jews numbered almost half of the town’s population.5 Jewish communities in other towns followed similar patterns of increase.6

The region remained a remote area, with few resources, almost no industry, and a mostly poor and illiterate population until World War I.7 Only two natural resources sustained the local economy: timber and salt, the latter found mainly in the mine in Aknaszlatina (Solotvyno) in the far eastern part of the region. The salt deposits in Subcarpathian Rus' yielded more than one hundred million kilograms in 1912, which was worth almost twenty million kronen (around four million US dollars at the time).8 Otherwise, lack of development marked the area. In 1910 only fifty industrial businesses with more than twenty employees existed.9

The poverty of most Jews in Subcarpathian Rus' enhanced their conservative outlook on life and traditional thinking. They looked to their local rabbis for authority in every aspect of life. Such power bestowed control, which rested in the rabbis’ hands and was manifested institutionally through their domination of communal bodies and yeshivot,10 as well as in the daily routine of Jewish life. Large families rendered the struggle to make a living especially difficult, but the influence of religious figures ensured the persistence of such traditional practices, and the isolated environment of the region throughout the nineteenth century reinforced this cycle. The social structure and hierarchies thus barely changed until World War I.

These internal characteristics suited the interests of the Hungarian rulers, who regarded the area as a colony.11 The elites that governed the Hungarian Kingdom from 1867 onward had consistently sought to establish Magyar demographic dominance in the areas they controlled. Until World War I they chose aggressive “magyarization” as a means to create a Magyar majority in a kingdom with substantial non-Magyar populations. This policy focused on measures aimed at education and religious institutions—the main places where people acquire their sense of identity.12 These attempts in Subcarpathian Rus' failed for the most part, notwithstanding their success among Carpatho-Ruthenian Greek Catholic priests. While many priests adopted Hungarian in the liturgy, their parishioners eschewed it in daily life. Living in remote localities throughout the region, the vast majority of Carpatho-Ruthenians continued to speak local dialects and remained distant from Hungarian culture.13 Most Jews in Subcarpathian Rus', who also lived in the small towns and villages throughout the region, continued to adhere to their way of life as well, even as many of those who settled in the towns at the foot of the Carpathian Mountains learned Hungarian.14

Seeking ethnic dominance, Hungarian leaders feared Russian influences in the region, including Orthodoxy. This phobia of Slavic culture, heightened by the interest of Russian scholars and politicians in Subcarpathian Rus' in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth, culminated in a series of trials between 1904 and 1914. The most infamous of these took place in Máramarossziget (1913–1914) against ninety-four Carpatho-Ruthenian farmers who had converted to Orthodoxy and were accused of treacherous ties with Russia.15 Sharpened by the failure of “magyarization,” these trepidations would return to shape state policies with fatal consequences when Hungary ruled the region during World War II.16

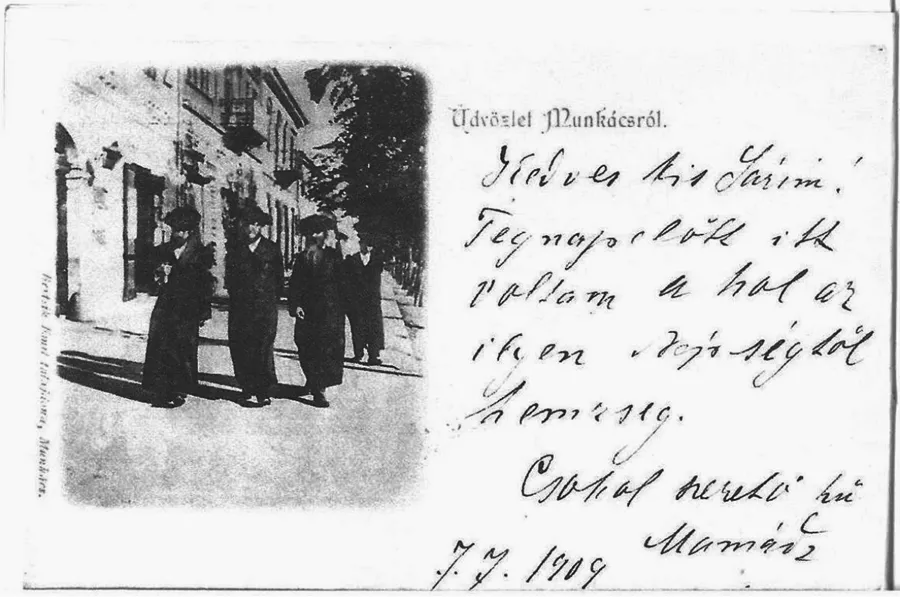

Hungarian authorities were not alone in their arrogant and contemptuous treatment of the local culture of Subcarpathian Rus'. Most Jews in Hungary referred to Jews in Subcarpathian Rus' using words with degrading connotations, such as Ostjuden or Galitzianer; indeed, extremely religious and inward-looking, the region’s Jews stood at the opposite end of the spectrum from the enthusiastically acculturated community in Budapest, as well as in other places in Hungary.17 Thus, an article in the first edition (1884) of the Magyar Zsidó Szemle (Hungarian Jewish Review), a journal established by key figures in Hungarian Jewish life in Budapest, complained bitterly that the “backwardness” of Jews in Subcarpathian Rus' lowered the general cultural level of Hungarian Jewry.18 Examples from everyday life include a postcard from 1909 showing Orthodox Jews in Munkács; the card was sent by a Jewish woman to her daughter in Budapest. The mother’s words reflect her thinly veiled disdain: “The day before yesterday I was here [in Munkács], a place bustling with activities of residents of this kind” (fig. 1).19

FIGURE 1. Postcard depicting a street in Munkács, 1909, sent by a Jewish woman to her daughter in Budapest. Source: Private collection of Yitzhak Livnat, Israel.

Uniformity, however, hardly characterized Jews in Munkács or elsewhere in the region. Rivalries and friction defined relations between Hasidic rebbes. Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Greenwald, son of Rabbi Moshe Greenwald of Huszt (Khust), described these tensions, which at times led to blows between followers of different rebbes.20 Non-Hasidic Orthodox rabbis sometimes clashed with Hasidic leaders, but all of them united against the Neolog (Reform) movement in Hungary. The Neolog movement emerged in the 1860s as part of emancipation and acculturation processes and gave rise to a need to rethink and make sense of Judaism, its boundaries, and the political structures of the Jewish world. The only Neolog congregation in Subcarpathian Rus' came into existence in 1869 in Ungvár (Uzhhorod), withstanding the wrath of its critics until its dissolution in 1906.21 By World War I schism had become routine in Jewish communities in the region.22 It would persist, as Jews faced trying times in the interwar years and during World War II. Nevertheless, Jews in Subcarpathian Rus' shared a sense of belonging to Judaism as a religious and cultural heritage, even as it held diverse meanings. Yet another sense of a shared society prevailed in contacts between Jews and their Carpatho-Ruthenian neighbors.

Jews and Carpatho-Ruthenians

A diverse scholarship in the last decade, particularly on national indifference, has challenged analysis based on ethnic and national categories, which in effect recycles and reinforces ethnic and national discourses and ideologies.23 Jews hardly figure in these studies, however, and scholars of Jewish life in modern Europe, for their part, still tend to view Jews as fundamentally different and separate from the societies in which they lived, often treating non-Jews as members of fixed and distinct groups as well.24 As historians Israel Bartal and Scott Ury have recently argued, “Either under the influence of Marxist concepts regarding the dialectical nature of society and the inevitable historical process, or because of the rise of national divisions in eastern Europe, the Middle East, and other centers of Jewish life, relations between Jews and members of other groups in eastern Europe are often represented as the history of competition, contestation, and ultimately conflict between two ‘always-already’ oppositional camps that share little save a mutual need for division.”25 Indeed, such positions take a deterministic and ahistorical approach: they view interethnic relations in modern Europe through the framework of the ethnocentric nation-state, a political arrangement that emerged only after World War I. Assuming that this outcome necessarily grew from the historical circumstances and, then, using it to deal with very different times before World War I leaves virtually no room for alternative explanations.26 Treating the nineteenth century not backward from World War I but on its own terms reveals a different picture.

Such an examination of Subcarpathian Rus' shows that, although Jews and Carpatho-Ruthenians constituted different groups, they lacked strict collective boundaries and led lives that flowed into each other. Landscape accounted for much of this situation, generating close interethnic relations. The heavily forested and secluded Carpathian Mountains provided a fertile setting for the popular mysticism that framed the worldviews and daily rhythms of both Jews and Carpatho-Ruthenians even after World War I. From contemporary accounts we learn that many Jews believed in the supernatural capabilities of those they called “miracle rabbis.”27 That several decades later some Jews still recounted with considerable awe these beliefs, such as the alleged power of Rabbi Yosef Tzvi Dushinsky of Huszt to cause the death of a rival by simply raising his stick, attests to their strength.28 Indeed, many Jews viewed Hasidic leaders as authorities on every aspect of life. When a cholera epidemic broke out in 1831, a group of Hasidim in Munkács received instructions from their rebbe in Żydaczów not to consult physicians but rather “recite all of Psalms every week . . . recite ketoret [the biblical portion concerning burning of incense in the Tabernacle] before ‘May it be Thy will,’ and examine the mezuzahs to insure that they are ritually fit.”29 Folk remedies, a related approach to treating sickness, still seemed appropriate to many a century later, notwithstanding the work of Jewish physicians and pharmacists in the town.30

Many Carpatho-Ruthenians also preferred magical solutions over medicine. Pëtr Bogatyrëv, an important figure in Russian scholarship on folklore and ethnography in the early twentieth century, made several research expeditions to Subcarpathian Rus' during the 1920s and 1930s, keeping a diary of his observations.31 In one village, for example, he discovered that Jews and Carpatho-Ruthenians shared mistrust, fear, and hostility toward medicine. Yet, “after a Jewish child was cured following diphtheria vaccination,” members of both groups began to overcome these feelings tog...