![]()

Chapter 1

THE SECOND COMING

IT IS AS IMPOSSIBLE to know when photography began as it is to know when our first ancestors opened their eyes, but if we were able to locate one of these events, we would not have to search long for the other. The two photographic processes that were unveiled in 1839 by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre and William Henry Fox Talbot built on a number of earlier chemical experiments and discoveries, even the most cursory survey of which would include Angelo Sala’s 1614 discovery that a nitrate of silver darkens when exposed to sun, Heinrich Schulze’s 1724 realization that this darkening can be used to make an image, Thomas Wedgwood’s late-eighteenth-century attempts to do just that, and John Herschel’s 1819 discovery that hyposulphites can dissolve the unreduced salts of silver, which led to the invention of “hypo,” a photographic fixer. Pride of place, though, would be given to Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, whose chemical experiments resulted in the first photographic image.1

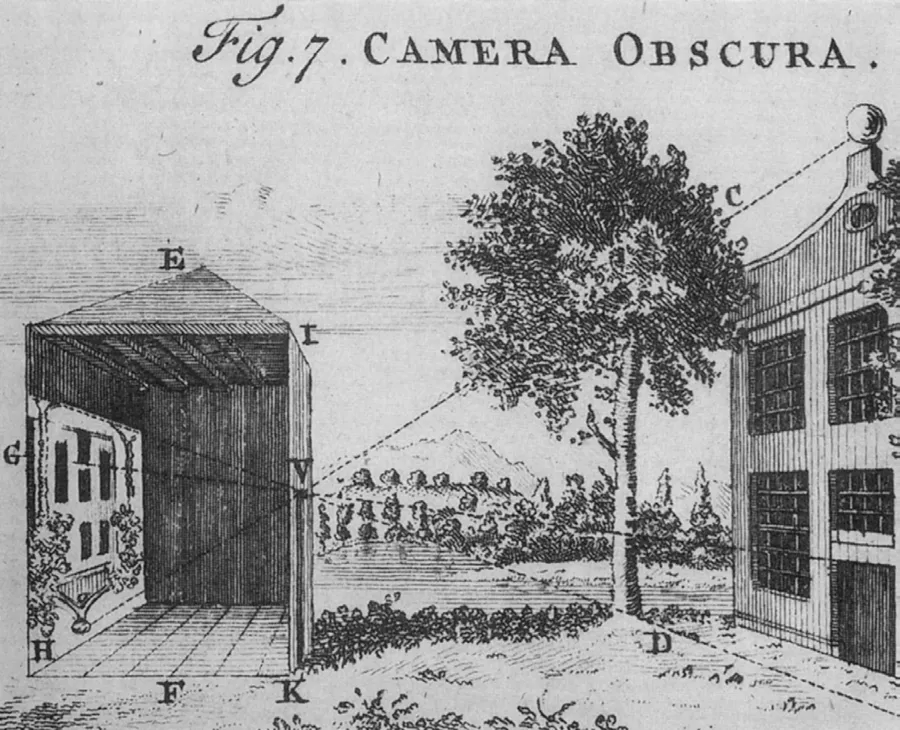

Figure 5. Thomas Jeffreys, Illustration from A New and Complete Dictionary of the Arts and Sciences, 1754.

Daguerre and Talbot also relied on a much older optical device: the camera obscura.2 The classical camera obscura—the one that was the norm from the thirteenth to the seventeenth centuries—was a darkened chamber with a small aperture through which light entered, bearing a reversed and inverted stream of images that both originated in the external world and analogized it. This continuous flow of mobile and evanescent images existed only in the “now” in which it appeared, and since the viewer had to enter the camera obscura in order to see it, the two were spatially as well as temporally co-present.

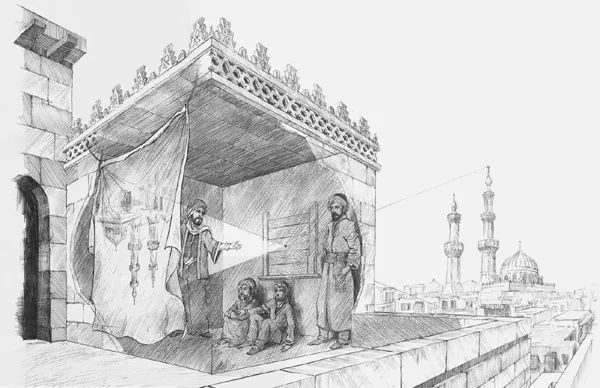

This device formalized optical principles that had been accidentally discovered centuries earlier and that are as old as light itself. In the fifth century b.c., the Chinese philosopher Mo Ti noted the “image-making properties” of a small aperture.3 A century later, Aristotle was struck by the many crescent-shaped images of the sun that appeared on the ground beneath a tree during an eclipse of the sun, and attributed them to the small spaces between the leaves.4 In the eleventh century, the Arab scholar Alhazen discovered the same principles while investigating the formation of images in a darkened room, and he viewed the sun during an eclipse from a similar place. He described the latter experience in the following way: “If the image of the sun at the time of an eclipse—provided it is not a total one—passes through a small round hole onto a plane surface, opposite, it will be crescent-shaped . . . If the hole is very large, the crescent shape of the image disappears altogether and the light [on the wall] becomes round if the hole is round . . . with any shaped opening you like, the image always takes the same shape . . . provided the hole is large and the receiving surface parallel to it.”5

Figure 6. Alhazan and his camera obscura in Cairo, Egypt, in the eleventh century. Courtesy of Ali Amro. © Muslim Heritage, Ltd.

“Receiving surface” sounds odd to a contemporary ear, since it suggests that the optical device that figured so prominently in the early years of chemical photography was receptive, rather than productive, but Alhazen is not the only early commentator who speaks in these terms; receptivity is a recurrent trope in pre-1700 accounts of the camera obscura. “When at the time of an eclipse of the sun, its rays are received in a dark place,” John Peckham observes in Perspectiva communis (1279), “through a hole of any shape, it is possible to see the crescent-shape getting smaller as the moon covers the sun.”6 “When the images of illuminated objects pass through a small round hole into a very dark room [and] you receive them on a piece of white paper placed vertically in the room at some distance from the aperture,” Leonardo da Vinci writes in Manuscript D, “you will see all those objects in their natural shapes and colors.”7 “If you have a piece of white paper or other material upon which [the images] of everything passing through the aperture may be received, you will see everything on the earth and in the sky with their colors and forms,” Cesare Cesariano remarks in a note in his 1521 translation of Vitruvius’s Treatise on Architecture.8 “The visible radiations [of] all [of] the objects without are intromitted, falling upon a paper, which is accommodated to receive them,” Sir Henry Wotton writes in his famous 1620 letter to Francis Bacon about Johannes Kepler’s tent camera obscura.9

Since the viewer had to enter the classical camera obscura in order to see its images, he was also a receiver.10 This would have been hard to ignore, because the device had no focusing mechanism. The only way the viewer could render its often hard-to-see images more legible was to move around the sheet of paper on which they were received until he found the point at which they came into focus—i.e., to participate in the reception process. Daniele Barbaro describes this practice in his 1568 book, La Pratica della perspettiva. “If you take a sheet of paper and place it in front of the lens,” he writes there, “you will see clearly on the paper all that goes on outside the house. This you will see most distinctly at a certain distance, which you will find by moving the paper nearer to or farther away from the lens, until you have found the proper position.”11

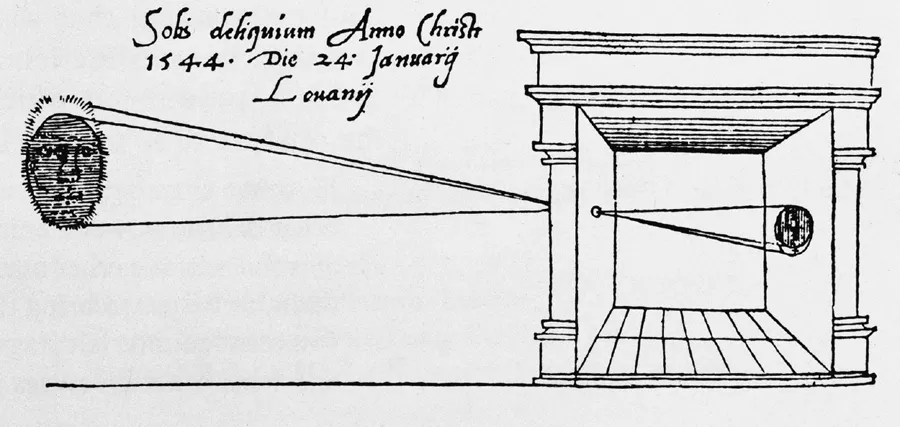

For centuries, the camera obscura was primarily used to watch solar eclipses, and it was put to this purpose because the human eye cannot tolerate the amount of light that floods into it when it looks directly at the sun.12 It consequently testified to the external source not only of the images that appeared on the screen, but also of those perceived by the human eye. So long as Christianity and Platonism were the dominant forces within Western thought, the notion that light enters the human eye from outside was unproblematic; illumination was, after all, a privileged signifier for both God and the demiurge. Since both systems of thought emphasize how blinding this divine light can be, the fact that a solar eclipse could be safely viewed only from the refuge of a camera obscura was also neither noteworthy nor particularly disturbing. And since the images that appeared within the device issued from a higher agency, they could be presumed to be a reliable source of information about what was happening in the external world.

Figure 7. Illustration from Gemma Frisius, De radio astronomico et geometrico liber, 1554. Courtesy of the National Media Museum/SSPL.

However, in 1490 Leonardo noted that the human eye also resembles a camera obscura—that rays of light enter its dark “chamber” through a “small aperture,” just as they do in the latter device, and that they also bear an inverted and laterally reversed stream of images.13 Because he was a largely secular thinker, he realized that both image streams originate in and refer back to a terrestrial source.14 He was also alive to their aesthetic properties. Leonardo likened the camera obscura’s images to “paintings,”15 and searched for other unauthored art works in the external world. “Cast your glance on any walls dirty with such stains or walls made up of rock formations of different types,” he advises his fellow artists in Ashburnham I, “If you have to invent some scenes, you will be able to discover them there in diverse forms, in diverse landscapes, adorned with mountains, rivers, rocks, trees, extensive plains, valleys, and hills.”16

I say “unauthored works of art” because Leonardo did not view image making as a strictly human activity. He believed that there is an aesthetic capacity in all worldly things that allows them to generate images of themselves. “Every body fills the surrounding air with infinite images of itself,” Leonardo writes in one notebook entry. “All bodies together, and each by itself, give off to the surrounding air an infinite number of images . . . each conveying the nature, color and form of the body which produces it,” he observes in another.17 This activity is self-presentational, and our look is its “lodestone.” Bodies give themselves to be seen by us by sending us analogies or “portraits” of themselves. Leonardo was also interested in a different kind of human art making—one that would begin with the acceptance of this gift. “The mind of the painter must resemble a mirror, which always takes on the color of the object it reflects and is completely occupied by the images of as many objects as there are in front of it,” he observes elsewhere in Ashburnham I.18

Ancient scholars had two conflicting theories of vision. For some, as James S. Ackerman explains, “the eye was passive and simply received emanations from the outer world,” but for others it was “active and cast out rays or a spirit to touch the seen object.”19 When Leonardo urges painters to let their minds be “filled by as many images as there are objects before it,” he might seem to be drawing on the first of these theories. In fact, though, he is only describing the initial stage in a complex process—one that is as much about giving as receiving. This process begins when the world conveys a visual analogy of itself to the human eye. The viewer receives this gift by relating it to similar things within his own memory reserve. Leonardo’s artist goes one step further: he generates an external analogy for the one created through the “marriage” of the world’s visual analogy with the viewer’s mental analogy. This opens the analogical network to other viewers.

Paul Valéry provides an excellent description of this process in “Introduction to the Method of Leonardo.” “At first the process [of receiving something] is undergone passively, almost unconsciously,” he writes, “as a vessel lets itself be filled: there is a feeling of slow and pleasurable circulation. Later . . . one assigns new values to things that had seemed closed and irreducible, one adds to them, takes more pleasure in particular features, finds expression for these; and what happens is like the restitution of an energy that our senses had received. Soon the energy will alter the environment in its turn, employing to this end the conscious thought of a person.”20 Daniel Arasse also talks about the unusual dynamism and reciprocity of Leonardo’s analogies, and says that the result is an “unfinished universality”—one oriented to the future.21

Leonardo isn’t the only early-modern viewer of the camera obscura who compares it to the human eye. Johannes Kepler also likens the inverted and laterally reversed images that enter this organ to those that enter the camera obscura, and he pushes the comparison a step further: he characterizes the retina as the ocular equivalent of the camera obscura’s “receiving screen.” “Vision . . . occurs through a picture of the visible object at the white of the retina and the concave wall,” he writes in his 1604 book, Ad Vitellionem paralipomena, “and those things that are on the right outside, are depicted on the left side of the wall, the left at the right, the top at the bottom, the bottom at the top.”22

Kepler calls this reversed and inverted “picture” the “retinal image,” and refuses to...