![]()

One

Antisemitism, Anti-Catholicism, and Anticlericalism

In 1902, the historian and Catholic political commentator Anatole Leroy-Beaulieu (1842–1912) published the first systematic comparison between antisemitism, anticlericalism, and anti-Protestantism.1 Before this time, authors in Germany and France who had related antisemitism and anticlericalism to each other had done so largely through polemics: Catholic antisemites often claimed that their political positions were a reaction to Jewish anticlericalism, while Jewish critics of the Catholic Church frequently argued that they were merely defending themselves against Catholic opposition to Jewish emancipation. Although Leroy-Beaulieu’s Doctrines de haine [Doctrines of Hatred] repeated these arguments, it also added what one scholar has called a structuralist explanation of these three forms of prejudice.2 According to Leroy-Beaulieu, a number of common threads connected all three discourses: Proponents of each type of hatred similarly expressed their positions in terms of economic rivalry, religious antipathy, and racial prejudice as well as in the form of fantasies about the political intrigues of their imagined enemy.

Offering a critique of interventionist secularism and “tyrannical statism,” Leroy-Beaulieu argued that all three doctrines of hatred resulted from the pressures of the modern nation-state.3 In each case, representatives of a particular group demanded the unity of the nation, which, they claimed, was threatened by Jews, Protestants, or the Catholic clergy in turn. Yet, in Leroy-Beaulieu’s estimation, it was not a particular group but rather the ideologies of antisemitism, anticlericalism, and anti-Protestantism that ultimately divided the nation. Leroy-Beaulieu’s interpretation was unusual in his day but has since become a mainstay of the historiography on the European culture wars of the nineteenth century. Most scholars now favor the view that the nations of modern Europe were divided primarily by their most militant unifiers.

For most of the twentieth century, Leroy-Beaulieu’s Doctrines de haine had little influence, despite the fact that its author is considered by many to be one of the greatest fin-de-siècle intellectuals and philosemites. Indeed, already before the Dreyfus affair, in 1893, Leroy-Beaulieu had opposed antisemites by writing a passionate and sophisticated apology of the Jews in a work entitled Israël chez les nations [Israel among the Nations].4 A Catholic liberal from the upper middle class who taught at the prestigious École libre des sciences politiques, Leroy-Beaulieu was a rare voice of dissent in a period when many saw Catholicism, monarchism, and antisemitism as complementary political commitments. Given his unusual position, many centrist republicans welcomed Leroy-Beaulieu’s intervention into the study of comparative marginalization as a noble endeavor yet soon forgot his work.5 Jewish activists and journals of the day also enthusiastically supported him but did so selectively: They applauded his opposition to antisemitism but ignored his arguments about anticlericalism.6 This disjointed reading of Leroy-Beaulieu’s oeuvre continues to inform current scholarship, even though historians interested in anti-Protestantism and the genealogy of French laïcité have recently revived his notion of doctrines of hatred.7 In general, the extensive scholarship on antisemitism has been less concerned with comparisons to the stigmatization and exclusion of other groups and more interested in establishing a singular narrative beginning with the history of Christian anti-Judaism. As a result, no study has picked up where Leroy-Beaulieu left off in 1902.

The dearth of comparative approaches is remarkable considering that Germany and France both gave rise to modern antisemitism and constituted focal points in the conflicts between liberals and Catholics. A vast literature on the history of antisemitism in both countries has explored how modern antisemites depicted Jews as members of an alien Oriental race whose attempts to gain wealth and social status weakened the position of their Christian neighbors. In tandem with this literature, a growing body of scholarship has pointed to the ways that liberals in the same countries portrayed Catholicism as backwards and similarly cast Jesuits as saboteurs who planned to subjugate the world and undermine the nation.8 While these two literatures have not developed in isolation from each other, few works have tried to explore the parallels and entanglements between these different forms of othering.9

Given the striking similarities between anti-Catholicism and antisemitism, it seems worthwhile to return to the comparative approach pioneered by Leroy-Beaulieu and to ask: Were different “doctrines of hatred” in fact connected during their formative phases? In which contexts did polemics against different groups reinforce each other, and in which contexts did they depart? This chapter pursues these questions by comparing antisemitic and anti-Catholic polemics in modern Germany and France, charting the emergence of polemical secularist politics through this double lens. By suggesting ways of rethinking the relationship between the claims different actors made against Jews and the Catholic Church in modern France and Germany, this chapter also offers a logical starting point for understanding the complex position Jews inhabited within the nineteenth-century European culture wars between liberal secularists and Catholics. Jews and Catholics alike had a fraught relationship with polemics that defined what secular citizenship and modern religiosity could mean. Focusing on the intersection of debates over the place of Judaism and Catholicism in different modern European contexts thus illuminates the stakes Jews had in depicting political conflicts in terms of a clash between a secular and a Catholic camp.

Although this chapter surveys the connection between antisemitism and anti-Catholicism in one long chronological sweep, my aim is to allow us to see new details of these discourses rather than flatten what we already know. I am therefore less interested in simply comparing these two phenomena and more concerned with exploring how they became entangled, reinforced each other, and together shaped different modern visions of political belonging and progress in two European countries. Although various modern thinkers and activists remained convinced that antisemitism and anti-Catholicism were diametrically opposed to each other, my analysis shows that secularism subjected Jews and Catholics alike to increased scrutiny, albeit with different consequences. Yet, I argue that it is not the hatred but rather the intense interest in Judaism and Catholicism as alien objects of inquiry that is most characteristic of European secularism in its various forms. In this interpretation, I take a cue from the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, who has referred to the depiction of Jews as radical Others—whether in the form of antisemitism or philosemitism—as “allosemitism.”10 What follows is thus a story not merely of resentments, as Leroy-Beaulieu would have had it. It is instead an analysis of secularism as a regime of knowledge based on both allosemitic and allo-Catholic views of Jews and Catholics as foils as well as models for thinking about which forms of religion could be considered politically acceptable. These models, much like their attendant polemics, were frequently shared by influential figures in Germany and France.

The Challenge of a Comparative History of Different Doctrines of Hatred

Before engaging with the entangled history of antisemitism and anti-Catholicism it may be useful to contemplate some of the challenges involved in undertaking comparisons between such fundamentally different forms of Othering. A history of the coevolution of these two doctrines of hatred must, first of all, take into account the different emphasis of anti-Jewish and anti-Catholic rhetoric. Depending on the context, antisemitic authors and politicians inveighed either against Jews, Judaism, or Jewish institutions. The same distinction could be made among authors who criticized Catholics, Catholicism, or the Catholic Church. To a large degree, slippage between these different targets is characteristic of the heated polemics against religious and political enemies. A pamphlet that railed against the immorality of Eastern European Jews might quickly become a condemnation of the economic power of all Jews, for example, just as a history of Jesuits might rapidly turn into a critique of Catholic superstitions or the allegedly anti-modern nature of the Catholic religion. Because such polemics have such a wide range of imprecise targets, any selective grouping of texts can give the impression that Jews and Catholics were stereotyped in a similar way.

Looking at the larger corpus of texts makes clear that this was not the case. Most liberal critiques were aimed against Catholic institutions, the influence of Catholic clergy, the persistence or revival of superstitions that allowed clergy members to control their flocks, and Catholicism as a religious culture. The targeting of whole Catholic populations was nonetheless uncommon in both Germany and France, in spite of several glaring examples of enlighteners and, later, liberals who employed Orientalist imagery to depict Catholics as insufficiently modern.11 Antisemites, by contrast, were primarily concerned with identifying the alien character of the Jewish population as a whole. Characterizing Jews as members of a different ethnic, racial, or national group, they argued against the political emancipation and social inclusion of Jews, an approach anti-Catholics seldom employed in their campaigns. Anti-Jewish and antisemitic activists and thinkers also rarely focused exclusively on rabbis, in contrast to anti-Catholicism’s focus on the Catholic clergy.12

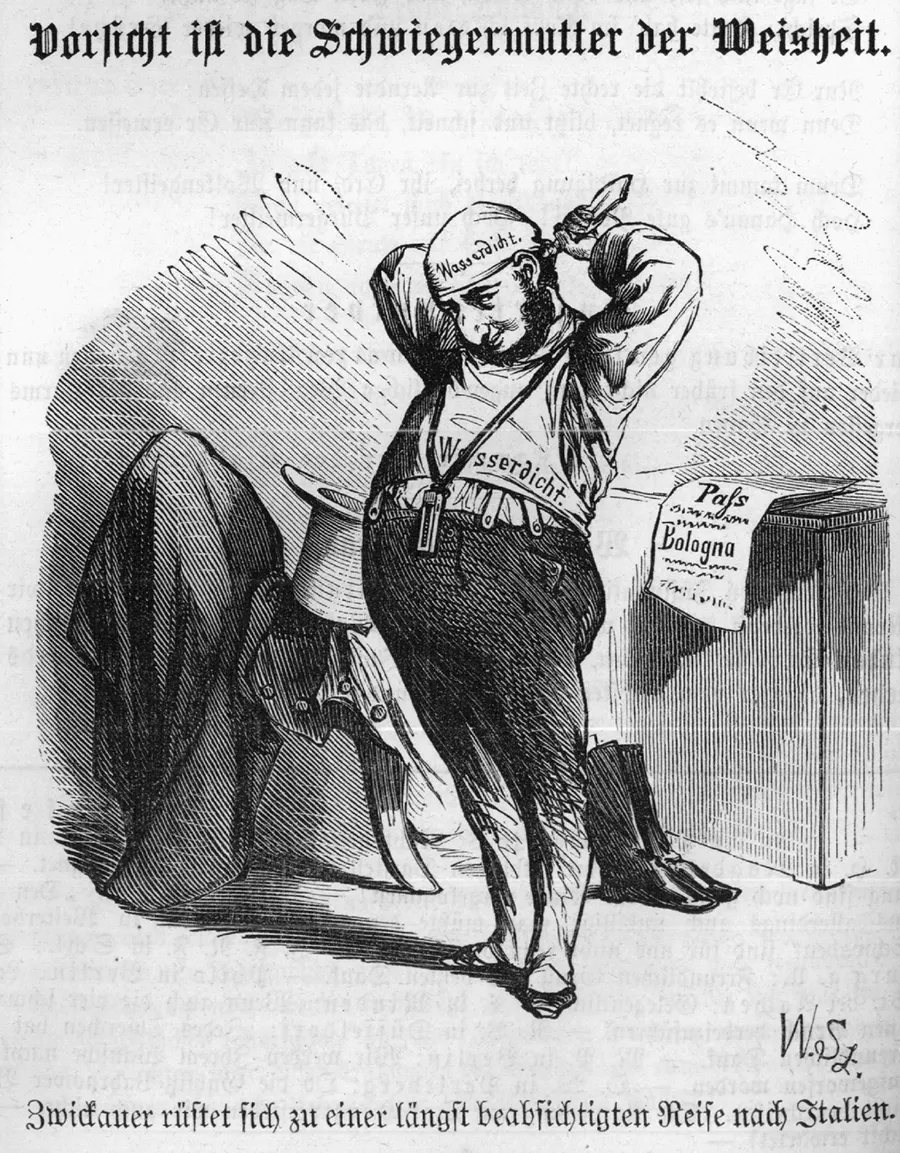

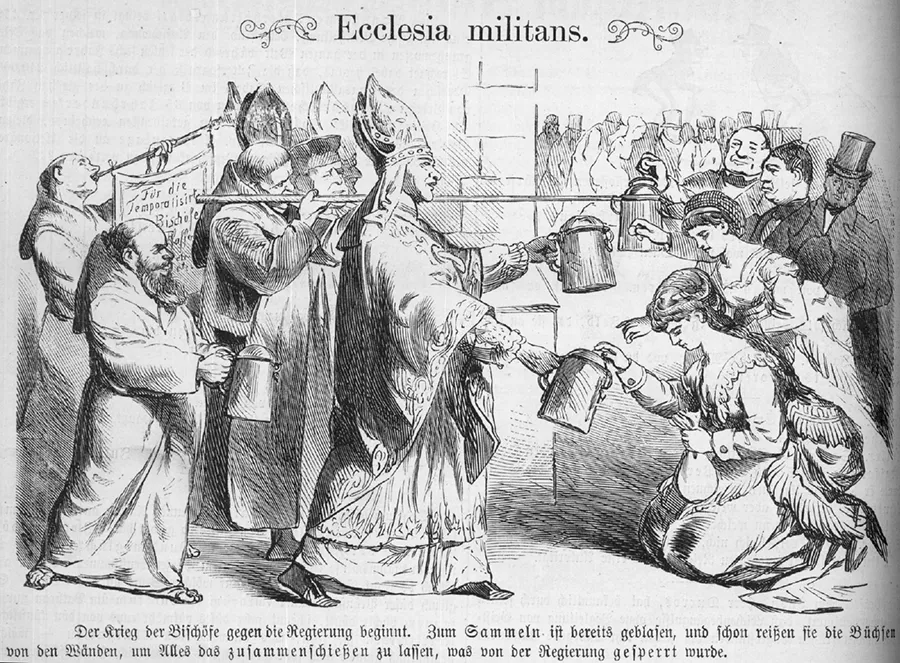

This different emphasis is most strikingly reflected in caricatures produced in Germany and France during the nineteenth century. While satirical magazines featured widely recognizable images of what they intended to be a Jewish type, they offered no equivalent of a recognizable typical Catholic. The accompanying two drawings from the Berlin satirical weekly Kladderadatsch illustrate this asymmetry. Both incidentally offer anticlerical messages. The first image was published during the debates on the Mortara affair of 1858, which erupted after Edgardo Mortara, a Jewish boy from Bologna—then part of the Papal States—was taken from his parents by the police following his baptism by a Catholic maid. According to the Roman authorities the boy, now a Christian, could no longer remain in the care of his Jewish family.13 The affair became a cause célèbre for liberals across Europe. It also occasioned a great deal of anticlerical and satirical commentary.

In the wake of the Mortara affair, many contemporaries contemplated the potentially absurd consequences of a scenario in which a person’s religion could be forever changed only because someone had sprinkled him or her with water. The first illustration offers a version of this type of humorous reflection: How could one protect oneself from baptismal water? Waterproofing, of course. The drawing shows a Jew putting on water-resistant clothing in preparation for his travels to Italy. While the illustration was intended as an anticlerical depiction, it employed standard allosemitic portrayals of Jews as essentially Other. Indeed, the only stereotypical figure in the drawing is the Jew, who is central to the satirical effect of the image. His figure—unlike the Catholic—was a stock character that could be used not only to consciously denigrate Jews but also to other ends, including anticlerical campaigns.

Figure 1.1. “Caution is the mother-in-law of wisdom. Zwickauer equips himself for a long-planned trip to Italy.” The headband and shirt say “waterproof.” Kladderadatsch, November 7, 1858, 208.

This contrasts with the second image, which depicts both the Catholic clergy and population in an unflattering way. To a large degree, the humor of the drawing is produced through the caption, which need not concern us here. On a visual level, the second illustration works through a conventional depiction of the costume and physiognomy of the Catholic clergy and draws on the familiar image of priests grown fat from overindulgence. The Catholics on the right of the drawing, by contrast, are stereotypical in their demeanor and perhaps in the prevalence of devout women, but they do not appear as caricatures of a single, easily identifiable type. Indeed, outside of the context provided with the illustration, they would not be recognizable as Catholics.

Figure 1.2. “Ecclesia militans. The war of the bishops against the government starts. They already sounded the call for collections and already they tear the collection boxes [or guns, Büchse] from the walls, to gun down everything that is blocked by the government.” Kladderadatsch, June 29, 1873, 120.

This contrast in visual representation hints at the fact that Jews and Catholics faced clusters of stereotypes with different emphases and implications about the possibility of their belonging to the nation. The trope of foreignness existed for both groups, but only the pair “Jews and Germans” or “Jews and Frenchmen” became an exclusive binary, whereas the opposition between Catholics and Germans or Frenchmen appears to have been unknown. Even ardent German Protestant liberals, who denounced Catholic beliefs and rituals as alien, rarely argued that Catholics could never be Germans. While claims of Jews’ foreignness and irreconcilable racial difference became the central accusation of modern antisemites, the primary charge hurled against Catholics was rather that they remained stuck in the past and insufficiently rational. Not surprisingly, most nationalists and liberals in nineteenth-century France and Germany alike considered it much easier to abandon irrationalism than an alien origin or character. This difference in stereotypes was particularly pronounced in France, where most inhabitants were at least nominally Catholics. In French liberal and republican polemics, the term Catholic was largely defined by political commitments rather than religious heritage. To be Catholic in France was not, as in Germany, to belong to a distinct religious community that could be ethnicized. These reflections suggest that, while certain tropes in antisemitic and anti-Catholic discourse were similar, the emphasis on themes of foreignness and progress often remained different in each case, as did the particular targets of each of these doctrines of hatred. To continuously mark these differences, I therefore resist literary convention and address the connections between anti-Catholicism and antisemitism with asymmetrical terminology: In the pages that follow, I will refer less frequently to depictions of Jews and Catholics and more often to depictions of Jews and Catholicism or Jews and the Catholic clergy.14

Another issue that raises methodological concerns is that of the differing levels of vulnerability experienced by the targets of antisemitism and anticlericalism. Whereas Jews were a small minority that did not constitute more than 0.5 percent of the population in France or 2 percent of the population in the German states, Catholics formed the majority in France and many regions of Germany. Even when Jews and Catholics were both small minorities in predominantly Protestant cities such as Berlin—where Catho...