![]()

PART I

DECOLONIZING THE MAGHREB

![]()

1

Souffles-Anfas

Palestine and the Decolonization of Culture

The first text explicitly to link Maghrebi culture and politics to the Palestinian question, the Moroccan journal Souffles-Anfas captures and exemplifies what I am calling transcolonial identification with Palestine: transnational forms of solidarity that are based on the understanding that Palestine and the Maghreb are part of an overlapping and unfinished colonial history. More explicitly than any other text in my corpus, Souffles-Anfas compares the plight of the Palestinians to the Maghrebi (post) colonial condition, including not only the experience of French colonization and acculturation but also continued French cultural and economic hegemony and the repressive tactics of the autocratic state. I argue that Palestine was a central interlocutor in the journal’s founding mission, “cultural decolonization”: the elaboration of cultural forms (literature, theater, orature, the visual arts), political models, and intellectual traditions that would break with both colonial (French) and pre-colonial (“traditional”) canons and norms.1 After June 1967, Palestine became the principal source of inspiration for Souffles-Anfas’ sustained reflection on language and culture, culminating in the launching of an Arabic-language journal, Anfas, and the dissemination of Palestinian poetry in French translation.

I begin, in medias res, with a poem that dramatically stages the kinds of political imaginaries I will be calling transcolonial in this book, an impassioned plea for solidarity with Palestine written in the wake of the Arab-Israeli war of June 1967:

my memory is long . . . Scars and grafts . . . weigh down my step but no longer stop my expansion

for a long time I dreamed They were nightmares Slow motion races of repetitive executions Whirling eyes Opium-burned demonstrations . . . Branded faces Cataclysmic winds The Atlas erupting in a deluge of collective memory

memory . . . You dictated to me the itinerary of violence

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I am the Arab man in History set in motion built anew by the vanguard of Palestinian guerrilla fighters

Arab Arabs Arab

a name to be remembered

great voices

of my seismic deserts

a people marches on

through 8,000 kilometers raises tents

command bases

how many are we

yes how many gentlemen statisticians of pain

advance a number

and the prophetic masses retort

with infallible equations

today

WE

ARE

ALL

PALESTINIAN

REFUGEES

tomorrow

we will create

TWO . . . THREE . . . FIFTEEN PALESTINES2

Abdellatif Laâbi’s “Nous sommes tous des réfugiés palestiniens” (We are all Palestinian refugees) intertextually inscribes Morocco and Palestine in a transnational history of popular protest and anticolonial struggle, culminating in a call to pan-Arab revolution. In this sense it constitutes a textbook example of the anticolonial fervor that swept across the Arab world after June 1967. It also perfectly captures the transnational character of what has come to be known as May ’68, and the centrality of anticolonial and Third Worldist thought to this event. The poem’s titular metaphor, reprised in the cascading layout and capital letters of the poem’s conclusion, appropriates “we are all German Jews,” the famous French slogan of May ’68, for Palestine, while the final tribute to Ernesto Che Guevara’s call to “create two, three . . . many Vietnams” places Palestine at the vanguard of world struggles for social and political justice.3 But what fascinates me in this otherwise typical if not cliché pro-Palestinian poem is the “itinerary of violence” it sketches from French colonialism and Israeli expansionism to what Laâbi elsewhere calls “internal colonialism”: the postcolonial state’s subjection of its citizens.4 Although the medical and bodily metaphors that punctuate the first stanzas of the poem (“grafts,” “scars,” “burns,” “branded faces”) are clear references to the physical and psychological violence of colonization, any Moroccan of Laâbi’s generation would have recognized that they also evoke an event that marked the beginning of the “years of lead,” as the repressive regime of Hassan II (1962–1999) came to be known: the violent repression of a student demonstration in Casablanca on March 23, 1965.5 The “cataclysmic winds” that usher in postcolonial violence project the poet into the arms of “the prophetic masses” marching to Palestine, metaphorically collapsing Palestine and the rest of the Arab world in a common front against colonialism, writ large to include past and present, foreign and domestic forms of oppressive rule.

Laâbi’s ode to Palestine was published in the fifteenth issue of Souffles (the plural of souffle, meaning breath or inspiration in French), a journal he founded with several poets and artists in 1966, ten years after Moroccan independence and exactly one year after the protests of March 1965.6 Initially a venue for experimental French-language poetry, from the second issue onward Souffles began publishing articles on popular theater, film, and art, and quickly became a platform for debates ranging from national culture and language to the continued effects of what its founders called “colonial science” on artistic and scholarly endeavors in postcolonial Morocco.7 In an editorial published after al-Naksa, Laâbi coined an expression that captures the journal’s broader cultural and political aim: “cultural decolonization,” the elaboration of literary and artistic forms that would break with French canons without seeking a return to tradition, which Laâbi, like Frantz Fanon before him, identified as a colonial construct.8 Souffles undertook this task on many fronts—scholarly production, the visual and performative arts, and cinema—but none more forcefully than poetry, its main focus from the outset. The texts published in the journal remain some of the most exciting examples of “linguistic guerrilla” from the era, to use Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine’s felicitous turn of phrase: the irreverent, iconoclastic use of the colonial tongue, French, to decolonize Moroccan culture.9

Souffles-Anfas played a seminal role in the fields of Moroccan and Maghrebi literature, shaping debates about genre, form, language, and popular culture that continue to be central to the field today. From the first issue onward, it published iconoclastic and formally inventive texts, for the most part experimental poetry written in French, and later in Arabic as well, by the likes of Tahar Ben Jelloun, Abdelkebir Khatibi, Mostafa Nissabouri, Malek Haddad, and Mohamed Zafzaf, now among the most canonic postcolonial Maghrebi writers. The journal clearly positioned itself on the Maghrebi cultural scene, breaking with what it characterized as “official pseudo-literature” (salon literature) in Morocco,10 and challenging predecessors such as Albert Memmi and Haddad, who famously prophesied the death of Francophone Maghrebi literature.11 Souffles-Anfas’ assessments of writers such as Kateb Yacine, Driss Chraïbi, and Rachid Boudjedra as well as its editorials on the role of the French language in Morocco made clear the journal’s commitment to decolonizing Maghrebi culture. Kateb in particular was singled out as the writer who had done most in this regard, through the invention of a Maghrebi “mythology” aimed at suturing the layers of Algerian history torn asunder by colonialism.12 As we will see, the journal also played a pioneering role in promoting dialogue between Arabic- and French-language writers in the Maghreb.

An essential compendium of early postcolonial Maghrebi literature, Souffles-Anfas also constitutes an important if neglected archive of 1960s political thought and experimental writing. The journal published key postcolonial texts such as “Toward a third cinema,” the manifesto penned by Argentine directors Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas,13 and the Black Panthers’ ten-point program.14 It was instrumental in introducing a Moroccan and Maghrebi readership to foundational anti- and postcolonial texts by the likes of Fanon, Amilcar Cabral, René Depestre, and Mahmoud Darwish. The journal’s internationalization went hand in hand with its political radicalization. After the communist militant Abraham Serfaty joined the Souffles team in 1968, the journal adopted an explicitly leftist orientation and became a tribune for politically divisive domestic issues ranging from education reforms and miners’ strikes to the status of the Western Sahara.15 In 1970, Laâbi and Serfaty founded a Marxist-Leninist party, Ilal-Amam (Forward), and the journal became a de facto mouthpiece for the party. Given the journal’s overtly leftist and oppositional stance, it is surprising it survived as long as it did, at the height of state censorship and repression. In 1972, Laâbi and Serfaty were arrested, tortured, and imprisoned, Laâbi for eight years and Serfaty for seventeen. After twenty-two issues of Souffles and eight issues of Anfas, the companion Arabic-language journal founded in 1971, the journal ceased publication.16

In part because of this singular and high-profile political trajectory, critics have tended to situate Souffles-Anfas in a national (Moroccan) or at best regional (Maghrebi) framework, neglecting its transnational dimensions. They have also tended to focus on the early, more literary issues of Souffles—the avant-garde poetry review rather than the Marxist-Leninist journal.17 Without downplaying Souffles-Anfas’ important role as a venue for postcolonial Moroccan and Maghrebi literature, as a forum for debates on Maghrebi culture, and as a key player in post-independence Moroccan politics, I argue that, after al-Naksa, Souffles-Anfas consistently placed Palestine at the vanguard of the cultural and political battles it was waging on the home front. In other words, the journal’s response to the renewed urgency of anticolonial struggle was to advocate for the decolonization of Palestine, seen as the vanguard of cultural and political resistance and renewal across the Arabic-speaking world.

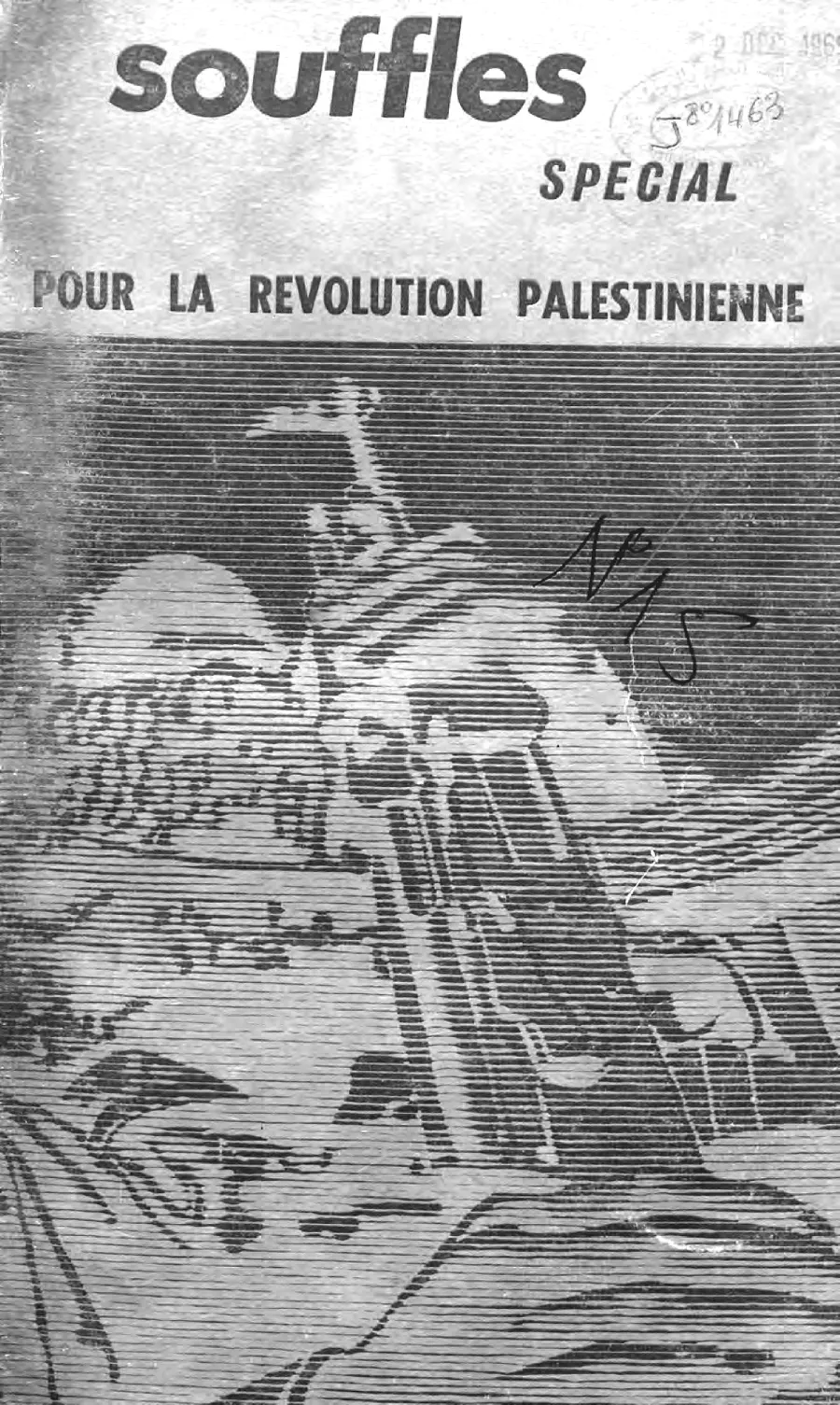

It is not a coincidence that Palestine played such a pivotal role in the journal. Souffles was founded just before the event that would put the Palestinian question on the map, in the Maghreb and globally: the Arab-Israeli war that began on June 5, 1967, and culminated in Israel’s annexation of Gaza, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem. The journal bears the imprint of this event and of the heady days of pan-Arab and Arab nationalist sentiment that followed. If the protests of March 23, 1965, were a foundational trauma for Souffles-Anfas at the national level, June 5, 1967, was its equivalent at the level of the “Arab nation,” which became a rubric in the journal after the special issue on Palestine. The ubiquitous image of the Palestinian guerrilla fighter, the feda’i (literally, martyr) donning his characteristic checkered headscarf, the kufiya, and carrying a Kalashnikov, is typical of the Pan-Arab iconography of the 1960s and reappears throughout Souffles-Anfas from the special Palestine issue onward (see cover image and Fig. 1). Yet despite its recourse to pan-Arab discourse and iconography, Souffles-Anfas distanced itself explicitly from adab al-hazima (“the literature of defeat”), the heterogeneous corpus occasioned by the crushing defeat of June 1967, seen not as a singular military reversal but as marking the decline of Arab civilization broadly speaking.18 In contrast to this corpus, the editorial of Souffles 6, published immediately after the war, marked the journal’s distance from invocations of patriotism, condemning instead what it described as a colonial war and warning against Arab states’ recuperation of nationalist sentiments.19 Unlike adab al-hazima, Souffles-Anfas did not lend Palestine a merely illustrative function. As I will argue, Palestine became a model of cultural decolonization for the journal, particularly in the domains of language use and poetic form.

FIGURE 1. Front cover of Souffles 15 (1969), special issue “For the Palestinian Revolution,” by Mohamed Chebaa. Source: Bibliothèque Nationale du Royaume du Maroc (BNRM). Reprinted with permission.

Published two years after the June 1967 war, Souffles’ special issue on Palestine, titled “Pour la révolution palestinienne” (For the Palestinian revolution) crystallizes in condensed form the ways in which Palestine came to signify the colonial in the journal, broadly defined to incl...