![]()

1

A Tale of Two Settlements, 1546–1559

In the early conquest period Spaniards needed little more than rumors of precious metals to launch exploratory campaigns. By the mid-1540s, tales of rich silver deposits in the northern province of Nueva Galicia (New Galicia) circulated among the region’s Spanish officials, settlers, and adventurers. As of then, the sparsely populated province, lacking in large sedentary native populations to exploit for tribute and labor, had proved a poor cousin to its central Mexican counterpart. But sometime in August 1546, the soldier turned explorer Juan (or Juanes) de Tolosa mounted an expedition from Guadalajara to an unsettled semidesert region in the northern central Mexican highlands that would forever change the province’s social and economic landscape.1 For below the surface of this inauspicious environment lay fabled quantities of ore. Extracted and refined, this silver bullion would yield the Spanish crown millions of pesos and underwrite the empire on both sides of the Atlantic.

Unsurprisingly, the leader of the search, Tolosa, became one of the four recognized Spanish founders of Zacatecas, the largest silver-mining town to develop in New Galicia. But should Tolosa and his Spanish associates receive the sole credit for this momentous discovery? A large number of Indians from central Mexico voluntarily traveled with Tolosa as guides or as foot soldiers. Other native peoples from distinct ethnic groups in the province also formed part of the expedition as servants and tamemes, or carriers. These indigenous peoples had been captured and then enslaved in numerous raids and military campaigns by Tolosa and his fellow invaders since the Spanish arrival to the area that became New Galicia in the mid-1520s. Other native peoples also played a critical role in the operation. While he was in the indigenous pueblo of Tlaltenango, for instance, several unnamed native men informed Tolosa and his party where to search for rich silver veins.2 The bounty of these initial strikes attracted other Spaniards and led to the establishment of a small real de minas, or mining camp, which eventually became the Spanish city of Nuestra Señora de los Zacatecas. While no native people rank among the city’s founders, without their assistance, Zacatecas, New Spain’s premiere silver-mining center for nearly three centuries, may never have developed.

Indigenous peoples not only supported the searches for precious metals but also authored their success. The survival and continued prosperity of Zacatecas, like its discovery, was by no means an exclusively Spanish enterprise. The city did develop under auspicious conditions, with rich silver veins and relatively little Spanish-indigenous conflict, but many a silver-mining town in the Americas followed a riches-to-ruins trajectory. Booms lasting several years, even decades, often gave way to busts, economic decline, and abandonment. The longevity and success of mining towns depended as much on the availability of a stable population base and a large skilled labor force as on continued silver strikes. As Zacatecas expanded in the mid-sixteenth century from a mining camp, or minas, to a Spanish town, non-Spaniards, particularly native peoples, provided the city with the bulk of its labor force, settlers, and long-term vecinos.

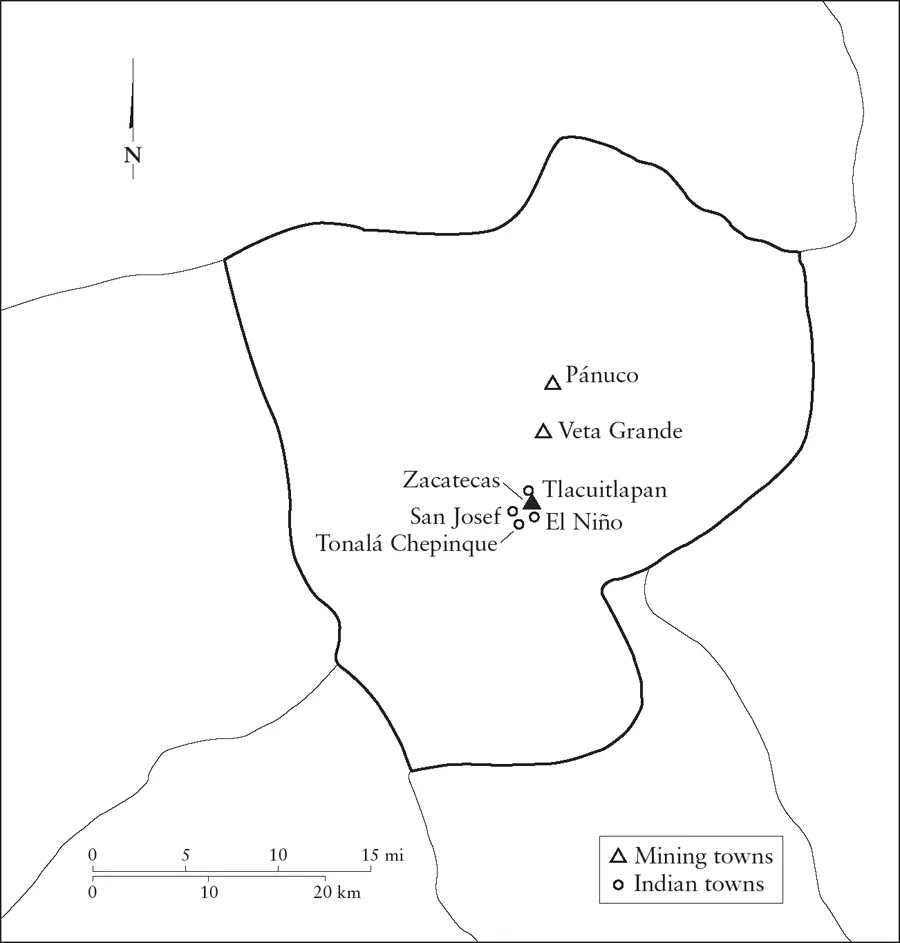

This chapter examines the history and contributions of the city’s indigenous residents in the settlement of Zacatecas from its precolonial past through the formal establishment of Spanish municipal government in the 1550s. It considers the role of Zacatecas’s preconquest indigenous population in the city’s early development, the impact of Spanish dependence on the foreign Indian population to meet labor needs, and the evolution of Spanish and indigenous settlements from rudimentary mining camps to urban communities. Many individuals from various ethnic groups participated in the founding of Zacatecas. But native peoples, this chapter argues, played a critical role in the city’s survival and early prosperity. While the local native population, the Zacatecos, were not numerous enough to meet Spanish labor demands, their relatively peaceful abandonment of their traditional settlement sites allowed miners and laborers to focus more on silver production than on defense during Zacatecas’s early years.3 Nor could Zacatecas have prospered without the large migrant Indian population from central and western Mexico that displaced the Zacatecos. These newcomers provided the necessary labor for the emerging mining economy and its subsidiary activities, and by creating indigenous communities, they brought into being a permanent and long-term labor source. But the founding of Zacatecas was not simply the story of how native peoples supported colonial projects. As the indigenous workforce established roots in the town, native peoples began adapting the Spanish urban milieu to meet their own settlement needs, exploiting Zacatecas’s frontier setting and labor shortages to derive some concessions, such as mobility, wages, freedom from tribute and repartimiento (rotary labor drafts), and the right to form their own semiautonomous neighborhoods. From its discovery and founding, the evolution of Zacatecas was the tale of two settlements: one Spanish and one indigenous (see Map 1.1).

MAP 1.1. Zacatecas and its Indian towns. Based on Peter Gerhard, North Frontier, 157.

Early Indigenous Peoples and Settlements

When Indians and Spaniards arrived at the site of the initial silver strikes in 1546, they saw no signs of complex, sedentary indigenous populations with hierarchical urban communities such as those they had encountered in their initial invasions to the south. They dismissed the Zacatecos—the small bands of nonsedentary and semisedentary peoples who sporadically inhabited the area—as barbaric and uncivilized, and of little use to their colonization projects. But the area around Zacatecas had witnessed sedentary activity more than a thousand years earlier. Little is known about these distant precontact peoples, the forerunners of the Zacatecos. These native peoples left fewer traces of monumental architecture or material culture than their Mesoamerican counterparts.4 Yet the sites they created served as important population epicenters in the region long before Spanish contact.

Native peoples lived near the area that became the city by the fourth century C.E. In writing about preconquest cultures in the area, archaeologists note that “the Prehispanic sedentary societies in Zacatecas started relatively late and reached complexity rapidly.”5 The earliest evidence of sedentary cultural activity comes from the western part of the current state of Zacatecas. According to archaeologists, the group of peoples now identified as the Loma San Gabriel Culture practiced sedentary agriculture and created ceramics from as early as 100 C.E.6 Over a thousand years before the Spanish conquest, several population and cultural centers of “Mesoamerican frontier farmers” developed in and around the western and southern zones of the state.7 Of these, the largest and most influential complex, the Chalchihuites culture, was centered in the western part of the state near what later became the mining boom town of Sombrerete. Three main population sites divided the south: the Malpaso Valley, the Juchipila region, and the Valparaíso-Bolaños Basin. Scholars remain uncertain as to the evolutionary connection between these sites and the extent of their social and economic interactions.8 Even if these settlements possessed a common foundation, regional distinctions developed over time that characterized each area. By the time of the Spanish conquest, the Cazcanes, a loose confederation of semisedentary peoples from the Juchipila area, posed the greatest challenge to Spaniards in the pacification of New Galicia. They played a prominent role in the significant indigenous uprising, the Mixton War, which engulfed the region from 1540 to 1542. Monuments and ruins of several other preconquest sedentary cultures are scattered across the state, such as the large structures of the Alta Vista/Súchil complex located near contemporary Chalchihuites, Zacatecas.9

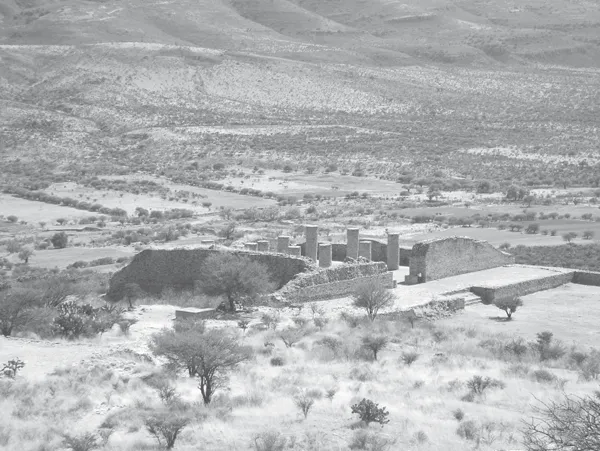

Complex sedentary cultures also flourished near Zacatecas. The ruins of one of them constitute the archaeological complex of La Quemada (also referred to as Chicomóztoc), located thirty-five miles from Zacatecas in the Malpaso Valley.10 Archaeologists believe that the La Quemada culture probably derived from a group associated with the Chalchihuites complex. Radiocarbon testing indicates that native peoples settled the site as early as 200 C.E. and that it remained populated until as late as 1450.11 Most scholars agree that the complex went through three stages: an agricultural stage circa 450 to 600; an apogee from 600/650 to 800; and a collapse, the date of which has yet to be determined, but which occurred well before the arrival of the Spanish. Present-day ruins indicate the grandeur and size of the settlement. Among its most impressive structures are a ball court (among the largest in Mesoamerica), a majestic hall of columns, twelve pyramids, and multiple stairways that connect several terraces and patios (see Figures 1.1–1.3).12

La Quemada’s frontier setting has stirred a debate over its purpose. Several scholars believe the city was an extension of the Chalchihuites complex or a colony of more southern groups such as Tarascans, Toltecs, or Teotihuacanos.13 Other researchers argue for a more defensive function, with the center serving as a fort to ward off attacks from outsiders or to serve as a sanctuary.14 However, some scholars argue for the site’s ceremonial role, finding evidence of banquets, ball games, and mortuary rites.15 In either scenario the complex served an important role as “the central place in a regional system of sociopolitical integration” in northwestern Mexico’s frontier zone.16 Three large communities of sedentary householders flanked the main site.17 In addition, a sophisticated road system linked La Quemada to hundreds of other population clusters in the area. There is general agreement that native peoples abandoned the community around the fifteenth century, signaling the withdrawal of sedentary agriculture in the region.18 Even after its desertion, the complex’s structures and location, in a fertile valley with a large river, continued to attract indigenous groups to the area. On their initial arrival in Zacatecas, Spaniards encountered a band of Zacateco Indians living at the foot of the ruins.19 Perhaps the site’s most important function was as a population epicenter.

FIGURE 1.1. La Quemada: “La Ciudadela,” or the “Citadel.” Photo taken by author in 2007.

FIGURE 1.2. La Quemada: Hall of Columns. Photo taken by author in 2007.

FIGURE 1.3. La Quemada: Votive Temple. Photo taken by author in 2007.

The Zacatecos

The decline of La Quemada did not mark the end of an indigenous presence in the region. By the 1540s, several loosely organized ethnic groups resided and intersected in the greater Zacatecas area, including Zacatecos, Guachichiles, and Cazcanes. According to scholarly classifications of native peoples these groups are considered semisedentary and nonsedentary.20 Sedentary peoples, such as the Nahuas of central Mexico, practiced permanent intensive agriculture, developed stable and complex settlement sites (including towns and cities), and possessed dense populations and centralized political and social hierarchies that facilitated the organization of labor projects and tribute collection. Semisedentary and nonsedentary peoples, in contrast, did not have dense populations or mechanisms for forced labor drafts or tribute.21 Both groups moved frequently and practiced hunting and gathering. But semisedentary peoples “were not nomads.”22 They practiced some form of seasonal agricultural and could have expansionistic ambitions. The Cazcanes, for example, possessed features of both sedentary and semisedentary peoples. They cultivated crops but did not employ tribute systems. These typologies of native peoples offer general guidelines. But the cultural diversity of the native peoples of northern Mexico defies general categorizations.23

Often semisedentary and nonsedentary peoples did not interest Spaniards because they did not serve their purposes: they lacked the political and social structures and organizations that facilitated the extraction of resources in labor or kind. Spaniards avoided settling in areas devoid of sedentary Indians unless a region, such as New Galicia, hinted at the potential for mineral wealth. Spaniards often homogenized these nonsedentary peoples, calling them Chichimecs, a term that central Mexican Indians had used to describe ...