![]()

PART ONE

The Haunted Past of Hope Township

![]()

CHAPTER 1

A Public Execution

A TRAGEDY TOOK PLACE IN 1939. Many years later, the villagers still clearly remembered the cruelty of the murder: a father’s anger had turned into a criminal act. The death on the riverbank lingered unpleasantly, and the people could not understand “his vicious heart, as a father.”1 This was the kind of utterance that we find in Shen Baoyuan’s retelling of the incident. She must have gleaned the narrative from villagers’ stories, bit by bit, adding along the way her own analysis and emotion. There seems to have been no report of it in Chengdu-area newspapers, even though the story, with its many tendrils, took place in nearby Chengdu, in little Hope Township (Wangzhen).

Before we move another step toward Shen’s (and in part my own) reconstruction of the morbid execution carried out by a Paoge master named Lei Mingyuan, we ought to physically locate the man, his daughter Shuqing, and Hope. The wide setting is rural Sichuan’s small locales, where secret societies ran untrammeled and free to exert power. The fine details of the incident played out not just anywhere in Sichuan, but around the Chengdu Plain. The area in general, although relatively isolated in earlier times, has been and still is one of the most densely populated areas of inland China. It was also one of the most affluent, and in an earlier time the province of Sichuan was one of only two provinces with a dedicated governor-general: other provinces shared such administrators. Rice production was the largest in the upper Yangzi region, benefitting as it did from the Dujiangyan irrigation system, which was originally constructed in the third century BC and still helps to control the Min River. The result was (and is) an ecologically stable and attractive region (see map in the Introduction).

In modern scholarship the most important and influential study of Sichuan was made decades ago by anthropologist G. William Skinner. It deals mainly with marketing structures in the Chengdu Plain and provides an analytical model of the way local markets fit into local people’s needs and how everyday economic life was tied at many different levels to these market structures.2 After Skinner, a glaring need for a social-historical analysis of this area of Sichuan resulted in a new sort of research. My own work, published in 1993, answers a part of this need. I have provided a general picture of developments starting in the early Qing period, and my findings have focused on both the rising world of migrants at that time (a situation that has been characterized through the expression “filling up Sichuan with Hunan and Hubei people” [Huguang tian Sichuan]) and the related problem of shortages of arable land factored with steep population growth since the mid-Qing era.3 Thus few people in the last century can have claimed they were descendants of Sichuan natives.4

In late Ming and early Qing times the area was plagued by war. In 1644, for example, Zhang Xianzhong, leader of the peasant rebellion, took Sichuan and established a regime when so many people were killed during the war.5 But by the early 1700s, Sichuan’s economy recovered and the immigrants poured in. The newcomers, despite their other dialects and ingrained duties to their native lineages and temples, tended to be active and striving; they set up guilds and native-place associations; they built shrines, temples, and association halls to service their gods, sages, and ancestors.6 They became heads of their associations as well as leaders of their local communities; they established connections with court-appointed officials and helped to provide for security, militias, granaries, relief and orphanages, philanthropy, and so on. These associations and the endemic populist, charitable programs that drove them became in some sense more important than clans or even the state itself, making the area a fertile ground for secret societies like the Paoge.

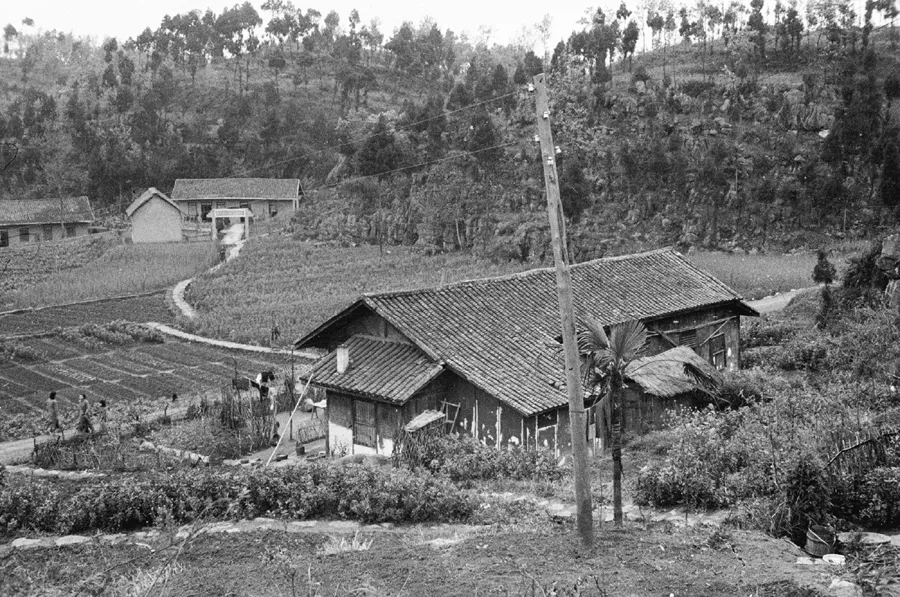

By way of contrast to the warm and productive Chengdu Plain, it is easy to imagine that in North China in the harsh winter it became increasingly difficult for households the more isolated from each other they were. Farming settlements in the north were therefore arranged cheek to jowl to fend off the demands of the environment. But people in the Chengdu Plain did not have such a problem. Settlement patterns in the more dispersed and much more commercialized Chengdu Plain saw looser relationships, and families lived relatively more independently. Strictly speaking, grouped families there should not be called villages; the term settlements might be more appropriate.7 Such interrelationships among settlements provided advantageous conditions for trade in the Chengdu Plain. In addition, the ubiquitous bamboo groves created a stable living environment, and good wells were plentiful. At the edges of the groves, other trees and crops were also planted, such as fruits and vegetables, offering a variety of agricultural products for trade in cash and food. Chickens prowled for food in the bamboo groves; ducks and geese wandered in paddy fields or ditches. If a stranger approached a house, a dog would bark. And out at the edges of the groves, farmers buried their venerated dead. The pattern of life, close to the fields, was an expected combination of work, daily routines, and tending to ecological systems (Figure 1.1). Lu Yongji, magistrate of Mianzhu county (Mianzhu xian) during the Kangxi period (1662–1722), wrote in one of his poems that “villages were withered and fallen after the war, and half the residents came from Hubei. Houses were built in the bamboo groves, and neighbors could see each other over the short distance.”8 On every anniversary of the death of their ancestors, family members and relatives went to the graves for rituals.

FIGURE 1.1 A typical scene in the Chengdu Plain in the 1940s: Farmhouses scattered around farmland. Source: Photograph by Joseph Needham, 1943–46. Reproduced courtesy of the Needham Research Institute, Cambridge University.

A classmate of Shen Baoyuan, Bai Jinjuan worked in a rural social survey project. She described a farmer’s house only a few miles away from Hope Township:

Woman Fu’s house is located on a small path three miles from the local market, surrounded by rice paddies, lush bamboo trees, and a bamboo-fence wall. The main gate of the house faces south. There are eleven to twelve rooms in the north, east, and west sections. Three north rooms have pass-through doors, and three east rooms have the same. An east side-room contains a kitchen, and the south room is the family hall for worship of the Buddha. A big west room is as large as four; it is a storage for grain and tools. In both the northeast corner and the kitchen, there is a small door going to the backyard, which has a stream dividing if from the paddy field. Along the stream there is a fence with a door leading to the stream for fetching water. By the stream there are large stones for washing clothes. In the yard also are bamboo trees and a line of pigsties, feeding eight pigs. The toilet is south of the pigsties. At two sides of the main gate, straw sheds are built for the water buffalos.9

If we think that Woman Fu was a landlord or at least a rich peasant, we would be wrong. Fu was actually a tenant, a widow over fifty, still with several children.10 People like her, toward the poorer end of the spectrum, had numerous ways to earn cash, see profits, and stay afloat. A high-density network of rural markets was established in the Chengdu Plain by which farmers traveled an average of fewer than five kilometers to reach a market. Chengdu was the commercial base of the whole region, and a well-developed trading system was established centered on it, including regional centers, local towns, town markets, and rural markets.11 There were market regulations that prohibited “bad practices” such as cheating and monopolizing. If a dispute occurred, mediation would occur to avoid violent conflicts. The area Shen Baoyuan investigated was very close to the place Skinner studied (Zhonghechang in Map 2).12 According to Skinner, the market network schedule, which avoided conflicting trading days, encouraged small traders. Rural peddlers traveled the market schedule, circulating goods between the central market and the small markets. Rural markets were an important place for socialization, where people could use wine shops and teahouses; peasants gathered for business or met friends, or discussed local news and events, official decrees, and gossip (Figure 1.2).13

The smallest rural settlement in the Chengdu Plain was called a yaodian (or yaodianzi); this rural shopping and trading nexus included such establishments as small grocery stores, teahouses, wine shops, and restaurants; usually these places had no more than one room for business. Yaodian often became social centers for rural areas. People always went to them for their pastimes, and the Paoge master Lei Mingyuan himself spent countless days in a yaodian in the Hope Township area. In slack seasons people spent a lot of time at low-class teahouses. In the Chengdu Plain many landlords lived in the market towns, where entertainment was limited, so teahouses were centers of amusement for them as well.14

In Sichuan many such places were run by the Paoge. This brings us to the question of Hope Township, a small settlement dotted just outside Chengdu, on the large, well-settled plain. We do not know with absolute certainty what or where this town was. One of the purposes of this chapter is to arrive at the best possible answer. We know that Shen Baoyuan did not use real names in her report. In the preface she wrote: “Because this thesis is a study of a secret society and its leaders, it is not necessary to disclose the objects of study; this is the professional ethic of social workers.” Shen wrote about “Hope Township outside the West City Gate of Chengdu,” but one notices that there does not seem to be a “Hope Township” on any historical record or today’s maps. Shen did not state that she changed the place-name, but it is quite probable that she did. Fortunately, a locatable village may be the right candidate.

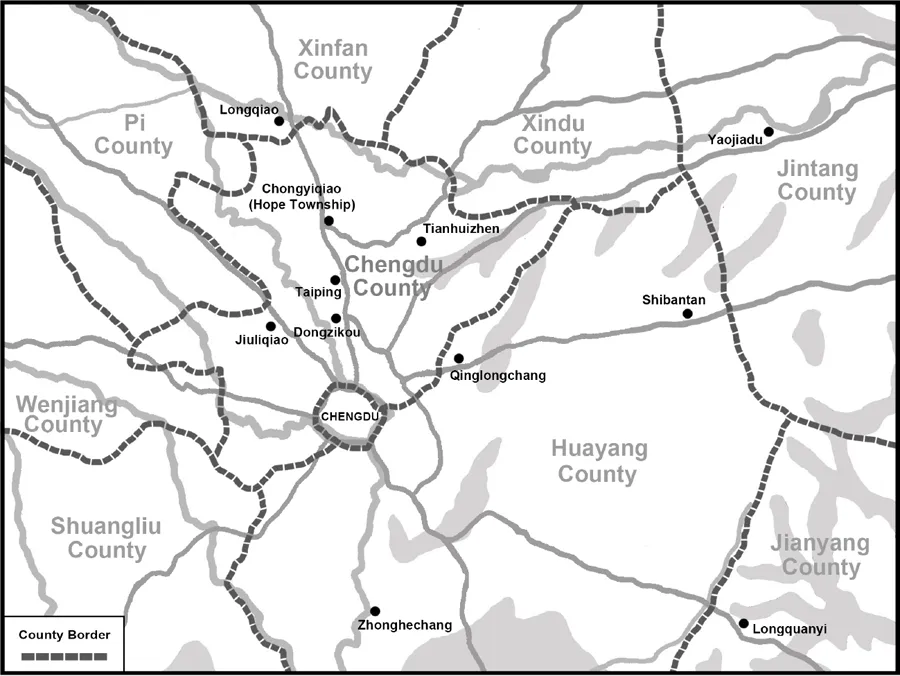

MAP 2. Chongyiqiao (Hope Township) and the surrounding area

Chapter 11, “Looking for the Storyteller,” recounts my contact with the elderly Shen Baoyuan, who now lives in Guangzhou. I failed to get useful information from her about Hope Township, however, so I pressed on in my hunt. I gathered information about Yenching University’s campus in Chengdu and found the following passage in the entry of 1945 from the appendix of a chronicle of events given in a 1999 book titled A Draft History of Yenching University (Yanjing daxue shigao): “When the summer break started in mid-July, student organizations of Yenching University organized and funded two rural service groups (xiangcun gongzuo fuwutuan), working with West China University (Huaxi daxue) and Ginling College (Jinling nüzi daxue). They traveled to Longquanyi and Yaojiadu (see Map 2), in Jintang County for one and a half months’ activities of rural education, hygiene, anti-Japanese propaganda, and surveys of rural society.”15

FIGURE 1.2 A street in a rural market town in Sichuan. Source: Photograph by Joseph Needham, 1943–46. Reproduced courtesy of the Needham Research Institute, Cambridge University.

This time frame is consistent with that described in Shen’s 1946 report: “The first day we arrived in the village was July 14, and during five days, until July 19, we visited all kinds of people, especially local leaders and leaders of the [Paoge] society. . . . For one month and five days, from July 19 to August 24, I collected materials every day for my thesis.”16 Shen’s investigation of Hope Township therefore might have been a direct part of that summer agenda detailed in the Draft History of Yenching University appendix. She wrote: “At that time, through the support of the rural service from the student relief association (Xuesheng jiuji hui) and the Department of Sociology, I and two other classmates, and an assistant of our school, carried out pioneering work. We were ready to work hard in this place.” Shen revealed specifics about the project: “Our first work was to establish friendships with local people. Then we wanted to know the general condition of rural life, the situation of peasant families, and information about local power, etc. We planned to do work that included a peasants’ school [nongmin xuexiao], tutoring, medical service, epidemic prevention, health guidance, letter writing, lectures about current events, exhibitions of news and pictures, and screening of movies.”17 Here the “peasants’ school” was no doubt the “rural summer school” (nongcun buxi xuexiao) mentioned several times in her report.

The market town Longquanyi, mentioned in the Draft History of Yenching University, was in fact located southeast of Chengdu. Photographer Carl Mydans (1906–2004), connected with Life magazine, took many photos of Longquanyi in 1941. Shen made clear in her thesis that when she first went to “Hope,” or perhaps on other days when she ...