1.1 Pricey Plagues

In 1842, Edwin Chadwick published an influential report: the Report from the Poor Law Commissioners on an Inquiry into the Sanitary Conditions of the Laboring Population of Great Britain. It described the terrible social, environmental and living conditions experienced by the majority of people in England and Wales. The impact of this report was far-reaching and profound. It led to the Public Health Act (An Act for Promoting Public Health) being passed through the Houses of Parliament at Westminster in order to improve public health and to ensure

“more effective provision … for improving sanitary conditions of towns and populace places in England and Wales.”1

What Chadwick had recognised was that rapid industrialisation was transforming British society. Urbanisation was taking place on an unimaginable scale. Row upon row of cheap, poorly built housing sprang up as homes for the poorly paid factory workers who were needed to produce the factory goods. In sharp contrast, these goods were sold to generate the wealth and money that built the impressive town halls and municipal building that represented prosperity and define our city landscapes to this day. The lack of sanitation and abject poverty experienced by most factory workers inevitably resulted in the “4 Ds”: Dirt, Disease, Deprivation and Death. This pervasive squalor and the cramped living conditions, combined with poverty, was a perfect breeding ground for infections (Figure 1.1).2

Figure 1.1 Crowded living conditions in nineteenth century London. Over London—by Rail, an engraving; London, England, 1872. From London: A Pilgrimage. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dore_London.webp (accessed July 2016).

The Chadwick Act, as it became known, was a significant milestone for public health. The health of the British nation needed to improve. The problems caused by the ravages of disease and unmanaged sewage was not restricted to the poor and destitute slum dwellers. These problems affected the entire society and even the wealthy were not immune. The Chadwick Act set out the need for “The State” to play an active role in improving public health. The treasury provided funding to organise and run national and local boards of health that were accountable to the Treasury. Superintending inspectors and officers were appointed and individual town halls could request inspections if the death rates in their local areas were too high. Ultimately, the Act led to investment in the Victorian public sewerage systems and, at last, the public health of the nation started to improve.

It is easy to mistake Chadwick's motives as straightforward philanthropy. In fact, his motivation was money. The argument he used to negotiate his Act through parliament was an economic one. Chadwick reasoned that improving the health of the poor would result in fewer men (and women), who were used to populate the industrial workforces, dying from infectious diseases. This would result in a reduction in the numbers of families and widows left destitute after the main, male breadwinner had died. In turn, this would reduce the number of penniless, desperate relatives, widows and families seeking poor-relief and ending up in Victorian workhouses because they had no alternative. Money would be saved in the long term. Improving public health was cost effective.

In many regards, the Chadwick Act was a response to the crisis caused by a plethora of common endemic and epidemic diseases, such as syphilis, gonorrhoea, whooping cough, scarlet fever, smallpox, dysentery, diphtheria, tuberculosis, measles, the plague, typhoid, typhus and influenza, that regularly ravaged industrial Britain. These diseases were not confined to the British Isles or even to industrialised nations. Infectious diseases were, and are, a global concern. They affect humanity across every society and habitable continent. Even today, infectious diseases recognise no boundaries nor borders. Human, as well as animal migration facilitate their deadly spread across the globe and throughout history they have been accompanied by a devastating loss of human life.

Looking back at statistics gathered more than 100 years ago at the beginning of the twentieth century, infectious diseases caused by microbial pathogens were responsible for the majority of human disease and death (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Top ten recorded causes of death in the USA in 1900.a

| Rank order | Cause of death | Number | Rate per 100 000 mid-year populationb |

| All causes | 343 217 | 1719.1 |

| 1 | Tuberculosis | 40 362 | 202.2 |

| 2 | Pneumonia (all forms) and influenza | 38 820 | 194.4 |

| 3 | Diarrhoea, enteritis and ulceration of the intestines | 28 491 | 142.7 |

| 4 | Diseases of the heart | 27 427 | 137.4 |

| 5 | Intracranial lesions of vascular origin | 21 353 | 106.9 |

| 6 | Nephritis (all forms) | 17 699 | 88.6 |

| 7 | All accidents | 14 429 | 72.3 |

| 8 | Cancer | 12 769 | 64.0 |

| 9 | Senility | 10 015 | 50.2 |

| 10 | Diphtheria | 8056 | 40.3 |

However, the next 100 years were a pivotal time span in a battle to rid the world of infections. The twentieth century is considered a golden age for public health. The scientific adventurers, visionaries and pathfinders, such as Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, Louis Pasteur, Robert Koch and Joseph Lister, ensured that by the turn of the twentieth century there was a much better understanding about the microbial causes of infection and disease. Knowledge about the relatively “simple” microbes, bacteria, fungi and virus, as well as the more complex parasites, such as trypanosomes and plasmodia that are responsible for malaria and sleeping sickness, had expanded. Humanity had entered an era where the importance of infection control was understood, better sanitation measures were adopted and vaccination programmes were implemented.

1.3 New Diseases

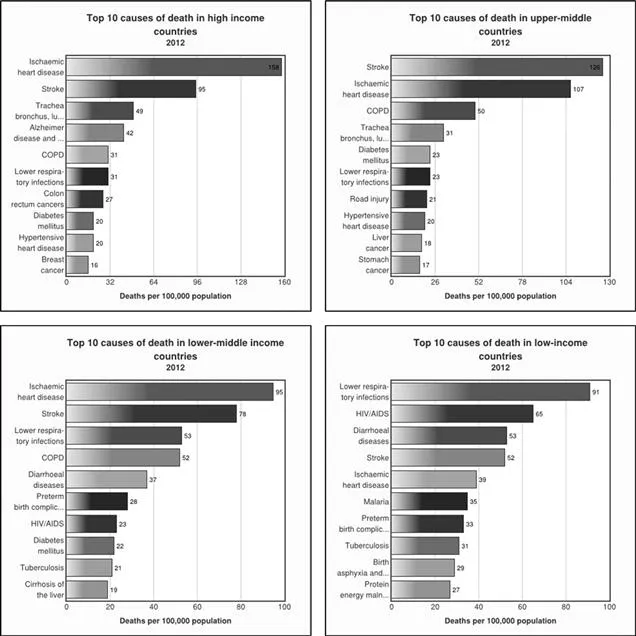

Sadly, the global optimism that infections were to be relegated to the past didn't last. Even now, at the beginning of the 21st century, infectious diseases are still a significant threat in developing countries (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Graph indicating the top ten leading causes of death in the world. Data retrieved from the World Health Organisation 3/5/2016: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/ (accessed July 2016).

Diseases believed to be vanquished to the past, such as tuberculosis and gonorrhoea, are becoming more and more difficult to treat and cure. In addition, the last decades have shown that society doesn't just have to contend with battling infectious diseases from the past. New infections are continuing to emerge that present significant implications for human health. As science and technology continues to develop, we seem to be unwittingly exposing ourselves to new pathogens, including bacterial ones. It is essential that society remains on high alert: emerging and re-emerging diseases need to be tracked and monitored.

In the United States of America (USA), during the early summer of 1976 the country celebrated its bicentennial anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence on the 4th of July 1776. Nearly three weeks later, on the 21st of July 1976, more than 2000 members of the Pennsylvania American Legion of war veterans celebrated this historic event during their annual three-day convention at the Bellevue Stratford Hotel, Philadelphia. Nearly two weeks later, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta Georgia was alerted: four veterans had died from suspected pneumonia after attending the convention. A cluster of cases soon followed. Veterans were reporting symptoms of mild cough, fever and, in some cases, a deadly progressive pneumonia. By the end of the epidemic, 182 members of the legion were diagnosed with this mysterious disease and 29 deaths were reported. This disease wasn't restricted to veterans. Another 39 people who had been in close vicinity to the hotel developed a similar disease and five additional deaths followed. A “new” airborne infectious disease had been identified. It took another six months—from the time the outbreak had been detected—before the bacterial perpetrator of the disease was identified. The bacterium responsible for this disease was Legionella pneumophila, just one of more than 50 species of Legionella that have since been isolated and, luckily, only a small fraction of these species cause human infection. Legionella are ubiquitous in the natural environment. They are found in freshwater systems, including lakes, rivers and thermal springs. But, Legionnaires’ disease is not associated with exposure to the bacteria found in these natural freshwater systems. The Legionella that cause human disease need man-made water systems and they are effectively spread through modern ventilation systems. Legionella have been shown to survive temperatures of 54 °C and below 20 °C. In cool conditions, the bacteria hibernate while they wait for conditions that are more favourable for growth.3 The resu...