![]()

Part 1:

The Principles of Game Work, the Encounter, and Story Theatre

The creation of something new is not accomplished by the intellect but by the play instinct acting from inner necessity. The creative mind plays with objects it loves.

– Carl Jung

![]()

1 Introduction to the Central Principles of Game Work

Improvisation and theatre games are at the core of what we teach at the Piven Theatre Workshop. Our goal for both the player and the actor is to be present and creative in the moment onstage before an audience – to be in a “state of play.”

Theatre games are the structures through which we play. Like all types of game, from children’s games to sports games, theatre games are based on a set of rules with an objective. Theatre games include running games, tag games, word games, movement games, dance games, story games, verbal games, ensemble-building games. Through this structuring of creative play, we build a supportive environment in which the player can take risks. Byrne captured that critical element of game work, the type of risk-taking that fosters “play” and “creativity,” when he wrote:

A “behind the back” pass in basketball; a “quick kick” in pro football (not done anymore); a “squeeze play” or “pick up throw” to third base in baseball: all of these are designed to catch the opposing team “off balance,” to force the players to improvise a response, to make a creative new movement – a new pattern, in fact, from an unaccustomed position. In theatre games, we are constantly trying to set up situations that catch the players “off balance.”

This breaking of programmed patterns, we have come to call “creativity.” It calls upon the whole being. The experience and stored energy of the past mobilize in the service of the unexpected moment. Something wondrous can emerge. So wondrous, in fact, that others begin to emulate it, to incorporate it into existing patterns and thus, new patterns of response are generated which must, in turn, yield to the next unexpected moment, the next “off balance” explosion of creativity.

That’s why our work is so carefully balanced between freedom and discipline. There must be a viable, organic pattern already in existence for the unexpected response to change, to transform. It is a process of fitting the individual’s unique and unexpected response into existing patterns that then become “something rich and strange” (From Ariel’s speech in Shakespeare’s The Tempest).

The structure of theatre games sets up the conditions for the “off-balance” moment, the moment that embraces all those elusive aspects of play – impulse, spontaneity, danger, and risk.

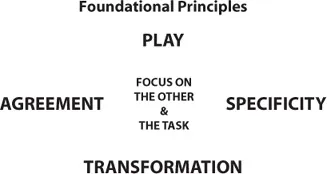

We have identified the underlying principles of improvisation and acting as: Focus on the other person and the task at hand; Play (Impulse and Spontaneity); Agreement; Specificity; and Transformation. In a note to the Workshop faculty in the 1990s, Byrne Piven stressed the importance of the underlying principles to his vision for the Workshop. His objective was “that the games taught, the sequences followed and the language used always be in accord with the principles of the work, that the process to which we have devoted our working lives is being realized.” He went on to explain why:

And it is because we ourselves are in constant reappraisal and, one hopes, constant creative evolvement. We are in constant search for better ways of opening, focusing, breaking through. Better sequences, calls, new games even, to realize the process of freeing the player.

The games we describe in this book are only one way to achieve this freedom. But we believe that, with an understanding of the relationship between the principles and the games, you can find your own path.

“A focus on the other person and the task at hand” is the foundational principle of game work. Viola Spolin first articulated this principle in the sixties through her groundbreaking book Improvisation for the Theatre,1 and it remains the single most important element to master in improvisation and game work.

This principle does not sit on the top of a hierarchy but rather forms the core of a circle. It is the necessary first step for realizing all the other principles – play, agreement, specificity, and transformation. Since all the principles have a role in every game, the same game may be used in relation to the other games to provide a point of concentration for a given class. The principles are separate in our discussion only for the purposes of analysis and explanation. In practice, there are no boundaries – all the principles are interdependent.

In our work, play, agreement, specificity, and transformation provide the means for discovering, exploring, and realizing the “encounter” at the heart of a drama, scene, or story. We use the term “encounter” to explain the visceral, emotional experience we seek to bring to life on the stage. The following diagram provides a graphic interpretation of all the principles we discuss and their relationship to one another.

The foundational principle

The necessary first step toward achieving play lies in the foundational principle of all game work: “A focus on the other person and the task at hand.” Most teachers of acting apply this concept in one form or another in their training methods, going all the way back to Stanislavski’s use of objectives. Shira Piven talks about the importance of the foundational principle to her work:

No matter what I am teaching or directing, I always go back to the basic, basic goal and principle, Spolin and Paul Sills’ Principle: helping the actor get “out of the head” by focusing on the task and the other person. For me it’s the impulse found in the Hassidic story that goes – if you had to explain the teachings of the Torah standing on one foot, what would it be? And the answer is: “Do unto others as you would do unto yourself.”

Like the Hassidic story, if you had to explain the essence of all game work, the answer would be: Focus on the other person and the game. If you can do that, you can get anyone to be present. And then there are all kinds of subtleties to explore.

That’s why the highly physical work is great because you just get people into their bodies and working together. It almost doesn’t matter what the game is – give someone a game to get them out of that self-conscious ego state. Think about this – the classic children’s bad acting is putting a child onstage and having them try to recite their lines correctly. In their heads, they’re thinking, Am I doing this right? Am I getting the lines right? As opposed to putting a child onstage and giving them some activity to do or some game or some task to perform and suddenly, they’re just being “themselves.”

I feel a great reverence for those basic, basic theatre games and principles. If you – in your gut – can learn that basic idea of point of concentration – of how to get out of your head by focusing on the task and the other person, if you know that, then everything else comes from that, like a ripple effect – it radiates out from that. And if you don’t get that, you don’t get any of it. That principle is at the heart of everything.

In this quote Shira articulates why we have chosen to place this principle at the center of all the other principles. Because whatever the game, that “off-balance” moment, that moment of creativity, that moment of play, cannot happen unless the players are focused outside themselves on the other and the task at hand.

The principle of play

Play informs all the work we do at the Piven Theatre Workshop. “Play” – being present and creative in the moment onstage before an audience – is what we seek. Learning the first principle opens the door to the second.

The word play is difficult to manage because it means so many different things in different situations. We play games, we perform plays, we play around. Someone asks, “What are you playing at?” to find out what your agenda might be. Someone says, “Stop playing around,” implying a lack of seriousness. At the Workshop, when you are “in play” we mean you are present in the moment – not thinking about the past or worrying about the future, but fully conscious and focused in the here and now.

To be as specific as I can, in our work play refers to:

- Experiencing and working “on impulse” with the other players.

- Exploring and heightening – words, emotions, characters, situations, ideas.

- Finding that creative motor that is capable of endless invention.

- Reacting spontaneously – freely and without planning. A reaction that surprises actors and players equally.

- Taking risks – the enactment of danger.

- Embracing the “anxiety of not knowing,” the “off-balance moment,” as the source of creativity.

Generally, we all think of play as a lively, free-spirited activity necessary for the health and well-being of the child – a time for fantasy, role-playing, make-believe, and fun. Most of all, it’s a time for exploration. A time, too, for perfecting motor skills: running, jumping, skipping, sports, baseball, and so forth. Somehow we’re not so sure about the necessity of fun or play for the adult. Play is quickly segregated to sports or physical activity. In school, fun and games are for recess – phased out by the fourth or fifth grade – or as a reward for serious work. Rarely is playing made an integral or organic part of learning.

And yet, we acknowledge the role of play in the artist’s so-called “work.” (Is he having a good time or what?). The result of the artist’s “play” is that we look at the world in a whole new way. For example, Picasso brought all our so-called linear perceptions together simultaneously in one canvas – cubism was born challenging our very definition of reality. Stanislavski coined that powerful “magic if” of imagination. Matisse, in the last phase of his life, wanted only to simplify – to get back to the child’s vision, uncluttered, pure, simple. So he pared down everything – threw out the paint and the brushes, leaving himself only scissors and colored construction paper – and he cut out a crude figure of a man, bottom-heavy, and called it “The Myth of Icarus.” Matisse thereby captured the human condition of Man, reaching toward the sky (God) while rooted to the earth. Playing allows us to reach beyond ourselves and art illuminates this condition.2

But playing is suspect – considered frivolous and an enemy to the serious work at hand. I remember a recent experience where a visual artist told me: “I do not play when I paint. I treat my painting very seriously.” Still, the artist generally is acknowledged as one who keeps and preserves that childlike sense of play and wonder and this sets him apart from the rest. But isn’t it true that others in society look askance at him, often for that very reason. What is he doing, playing? Having fun when we have to work so hard at the everyday drudgery of running the world?

Through theatre games and improvisation, we are creating a supportive environment in which a person can risk. It is hard to imagine real growth without an exploration that allows for risk. And so, to the artist who says, “I do not play when I paint. I take my painting seriously,” I say, “We take our playing very seriously. When we play, we are very serious. We are making connections and maybe even, with the help of the Muse (wonder of wonders), who knows, even art.”

The principle of agreement

Agreement is not only an important element of play and improvisation but it is also a central tenet in the unique actor–audience relationship of story theatre and a fundamental aspect of ensemble building. Webster’s Dictionary defines agreement as “being of one mind, in harmony and united in common purpose.” That is an apt definition for this principle. In the game context, when we say that a group is “in agreement,” we mean that the players are working together, giving and taking from one another and from the surrounding space in order to play a game, improvise a scene, find a transformation, tell a communal story. For example, when a group is moving in slow motion, they are in agreement only if all are moving at the same speed with the same quality of movement. To do this, each member of the group must be focused on all the others, mirroring the movements and speed that they see and kinesthetically in sync with the actions of those around them.

Agreement functions similarly in scene work. The players must be in agreement on all of the given circumstances of the imaginary world they are creating. For example, both improvisational scenes and story theatre involve the use of imaginary objects. When creating imaginary objects in a scene, the players must agree on the size, shape, weight, texture, and temperature of the object and maintain that agreement throughout the scene. If one or more players begin to lose their awareness of what the others are doing, the “reality” of the scene will be lost. If an imaginary sofa carried by a group suddenly gets longer and longer or begins to droop as two players let their hands drop and the other two are still holding their hands ...