![]()

PART ONE

Process and Animation

![]()

1

Processing Animation

This chapter will look closely at the numerous processes of animation. To facilitate this study, it has been divided into nine different thematic sections which together contribute to a fairly wide understanding of most approaches to animation. These sections will consider animation in terms of movement, metamorphosis, frames, forms, layers, sound, time, abstraction and the process-document.

Movement and animation

‘Cinema’, declares philosopher Gilles Delueze at the beginning of Cinema 1, ‘does not give us an image to which movement is added, it immediately gives us a movement-image’.1 For Deleuze, movement and its related image are inextricable in the cinematic image; they are recorded simultaneously and subsequently presented simultaneously to the viewer. In fact, from the perspective of the spectator it is quite difficult to consider anything independent of motion – whether it is on screen or in the actual world. A person walks along a path: that movement appears as an all-encompassing permutation of that person; a rock rolls down a cliff and its movement and form are undeniably simultaneous. Yet, when we consider the world in more processual terms we can appreciate that movement is a force that is enacted upon all things. A chair will not move unless pushed. Gravity forces the rain to fall downwards. We exert energy, and we stand up. Even when things do not move, we understand that at one time or another movement forces have affected them. Len Lye suggests,

the history of any definite form is the movement of which the form is the result. When we look at something and see the particular shape of it we are only looking at its after-life. Its real life is the movement by which it got to be that shape.2

Further to this, in Animate Form, Greg Lynn suggests, ‘force is an initial condition, the cause of both motion and the particular inflections of a form’.3 When we consider the world in more processual terms, we understand that movement is a force that is enacted upon all things. Henri Bergson hints at this conception when he observes that ‘In reality, life is a movement, materiality is the inverse movement.’4

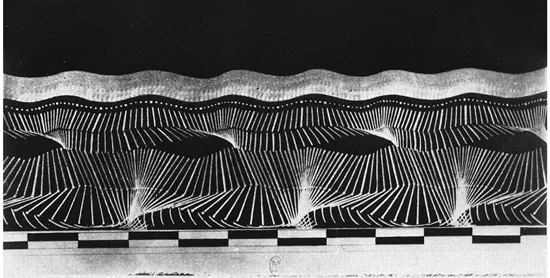

Live-action cinema, however, cannot record motion independently; it can only provide us with a movement-image in which movement and image are bound together. In order to consider pure motion, we need to disentangle it from form. There have been a number of processes emerging over the years that have attempted to record isolated motion from images. In the 1880s, Etienne-Jules Marey developed a ‘geometric chronophotographic’ system that allowed him to isolate graphic representations of movement that were discreet from the original subject. In one example he attached an apparatus (essentially just a multiple cross section of white sticks) to the subject’s back and sequentially photographed the subject walking. The white lines from the apparatus were then isolated in the resulting photographic images, then composited on a single plate detailing the ‘oscillations of the vertebral column, shoulder and hip’.5 In another version he attached white joint-marker points (connected by white lines) to a human subject. The subject was dressed completely in black and placed before a black background (see Figure 1.1). In the resulting images the person would ‘disappear’ leaving only the denoting white lines.6 These provided a simplified representation of human motion that effectively disentangled the human movement from the human form.

FIGURE 1.1 Composite image by Etienne-Jules Marey denoting abstracted movement.

Current motion-capture technologies do essentially the same thing. Motion-capture systems can be generally either magnetic or optical based; both normally rely upon the placing of points on an actor, which are then read by a series of sensors or cameras. A third type of motion capture, referred to as mechanical mocap systems, ‘directly measure joint angles of a capture subject who wears an articulated device that consists of straight rods and potentiometers’.7 These in turn provide a recording of essentially ‘pure’ movement, abstracted from the original form. A similar process, referred to as video-based motion capture, allows one to extract pure movement information from already existing film or video footage. Once the footage is digitized, one can use computer software to place tracking points upon specific parts of the image, which then allow for the motion tracking of the figure or object on screen. This also provides a recording of ‘pure’ movement, abstracted from the original form (in this case existing film or video footage). More recently, motion-capturing abilities are finding their way into everyday appliances such as video games systems and mobile devices. Each of these motion-capture systems represents a significant shift in the recording of pure motion and an effective method by which to consider movement abstracted from form.

Importantly, the process of animation construction does normally require that we consider motion and image as very distinct entities. This motion does not originally emanate from the characters or objects themselves. It is imposed from outside through the process of animation. Animation, in fact, directly contradicts Deleuze’s avowal that cinema ‘gives us a section, but a section which is mobile, not an immobile section + abstract movement’8 for, in contrast to live action, this is exactly the process of animation’s construction. Although motion capture expresses the most obvious amalgamation of abstract movement and image, nearly all forms of animation involve this process to some degree. In stop-motion, the puppet is physically built; the animator then physically moves it. In 3D computer animation, the object or character is virtually built, and then virtually moved. Even in the case of cel animation, the act of moving the cels or backgrounds in front of the rostrum camera, or the lowering or raising of the camera, creates some of the movement.9 But even in the case of exclusively drawn animation, in which the animator must encode each new drawing with motion rather than overtly add to it, one could argue that the animator must at least have an awareness of the pure motion, distinct from the form that they are engaged with, in order to create a convincing movement of that form.

One might consider the uncanny and utterly eccentric movement found in a Tex Avery short animation, such as Red Hot Riding Hood (1943), to be an epitome of classical animated films. But from a process perspective there is no concept of motion that does not exist both in the physical world and in animation. Removed from the animated context, every possible movement found in an animated film comprises exactly the same types of motion that we witness in the actual world (up, down, forward, back, left, right, accumulation and dispersion). The dancing of a bonfire flame, the splashing of water, the vibration of quantum particles: all represent a potentially greater eccentricity of motion – if it were to be applied to an animated form – than a Tex Avery cartoon has ever achieved. With regard to process, Nicholas Rescher asserts that all processes when removed from their concrete context become ‘inherently universal and repeatable’.10 Movement, when it is removed from its bodily context, also becomes ‘inherently universal and repeatable’. For example, in the feature film The Hulk (Ang Lee 2003), the director, himself, delivered the motion-capture performance of the animated Hulk character: his movements were then abstracted and applied to the Hulk 3D model. For Rescher, once a process is applied to an event, then it is ‘at once concrete and universal’.11 Similarly, the movement of the Hulk is not only the Hulk’s, but also that of Ang Lee; at the same time it is a pure movement (movements of up, down, forward and back) that can be applied to any other 3D model. The unique ability to separate the processes of motion and image allows for a new context and a greater complexity for both. A snail can move like a tornado, a triangle like an old man. As one stream of information plays off against the other, the combined meaning of such a disjoint may be superior to a synchronous narrative.

Animated methods

Traditionally, there have been two primary methods in the creation of animated movement. The first method, which can be referred to as manipulated animation, involves the manipulation of a single image or object. Most stop-motion puppet animations are produced this way – the animator will incrementally, but directly, move the forms. Cut-out animation, paint-on-glass animation and a lot of 3D computer animation are other clear examples of this manipulated animation process. Because this approach always involves the application of movement to a form (either directly by the animator or added via the motion-capture process), it represents a rather direct expression of how image and movement can be considered as distinct concepts. The second method is a form of animation that is best described as replacement animation. Replacement animation is arguably the oldest approach to animation, particularly if we consider its pre-cinematic (and pre-photographic) roots. It normally involves the creation of multiple completed images that are then sequentially replaced, one at a time, in order to create the illusion of a unique and persistent form that can move. Most instances of traditional cel animation would fall into this category. For example, 10,000 individual drawings of Felix the Cat and friends (each slightly different in pose) might have been necessary to produce a seven-minute animated film of the characters running about.

Additionally, most of the animation that would have been produced for such pre-cinema devices as the zoetrope, phenakistiscope or flipbook would have also been produced in this manner. Each drawing was in a sense encoded with difference which when played through an animation apparatus would produce the effect of movement. Nobody directly moved Felix (in the puppetry or stop-motion sense), but he was made to move by secreting bits of movement within the difference of each successive frame. Later in the 1940s, stop-motion animator George Pal applied this term when he developed his ‘replacement animation system’. Though he also animated his figures in the traditional stop-motion (manipulated) method, he also created a lot of the movement (particularly the more fluid effects of squash and stretch) through the replacement system. Thus, in order to make a figure’s arm stretch out to pick up an object, he would replace it frame-by-frame with a slightly longer arm (see Jasper and the Haunted House, George Pal 1942). Though replacement animation does not follow the literal and direct process of applying movement to form, the animator is certainly aware of this conception and the idea of ‘making the drawing-form move’ is more than likely the impetus of their efforts. And since this process does not allow for the direct puppetry-like movement of forms, the animator must encode each still image with movement. The result is that there is differential movement encoded within the interstices of the frames – in a sense a moment of encoded pure movement. On the other hand, it is important to acknowledge that even in the most direct puppetry-like animation technique, the animator will also need to consider, to some degree, individual moments and layers of constructive processes. Quite often these two traditional approaches will overlap both in technique and in theory.

However, even though most cel animation can be categorized as replacement animation, much of it (especially in limited animation) is also partially achieved through the use of manipulated stop-motion. For example, most background pans or zooms and even some simple character movements (such as flying through the air, or skidding along the ground) were achieved by the camera operator. Thus, not only would he or she take a photograph of each painted cel, but he or she would also be responsible for manipulating the plates and cels in a frame-by-frame manner, one increment at a time.

One animation process that often involves an important overlapping of manipulated and replacement animation processes is the technique of rotoscoping. The rotoscoping process was invented by Dave and Max Fleischer in 1917. Rotoscoping is the process by which live-action footage is traced from ‘single-frame projections’.12 Similar to motion capture, the process of rotoscoping involves the extraction of movement from one form, and its application, to another. Depending upon how carefully the original images are traced, the resulting motion information will either be comprehensive and faithful to the original or dramatically altered. In many cases, the animator will only trace (rotoscope) every other frame (or even every third frame) of live-action footage. In this case, the result will be a more jittery, anime-ic motion (a term coined by Thomas Lamarre). In addition to live-action footage, rotoscoping can also ‘capture’ the movement of existing animation. For example, this process was used extensively in the production of Disney’s Robin Hood (1973), in which animation from the studio’s previous features, the Jungle Book (1967) and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), were heavily reused through a rotoscoping process.

In a slight variation of the traditional rotoscoping process, Australian animator David Barker patented an animation process in 1921 in a number of the Commonwealth countries (Australia, England, Canada), which was essentially a facsimile of Fleisher’s earlier (1917) US patent. It too involved the tracing of live-action actors directly onto cels, and then the ‘opaquing in of the figures’. But what made his approach somewhat different is that he would frequently create large photographic prints of the original live-action film and use these as the background on which the ‘rotoscoped’ cel animation would be placed. These would then be photographed on an animation stand in the normal cel animation production process. The result was a hand-drawn form that was imbued with captured movement but then reconstituted back into its origina...