![]()

1

Intellectual Networks and Surrealist Objects

Gaming the system

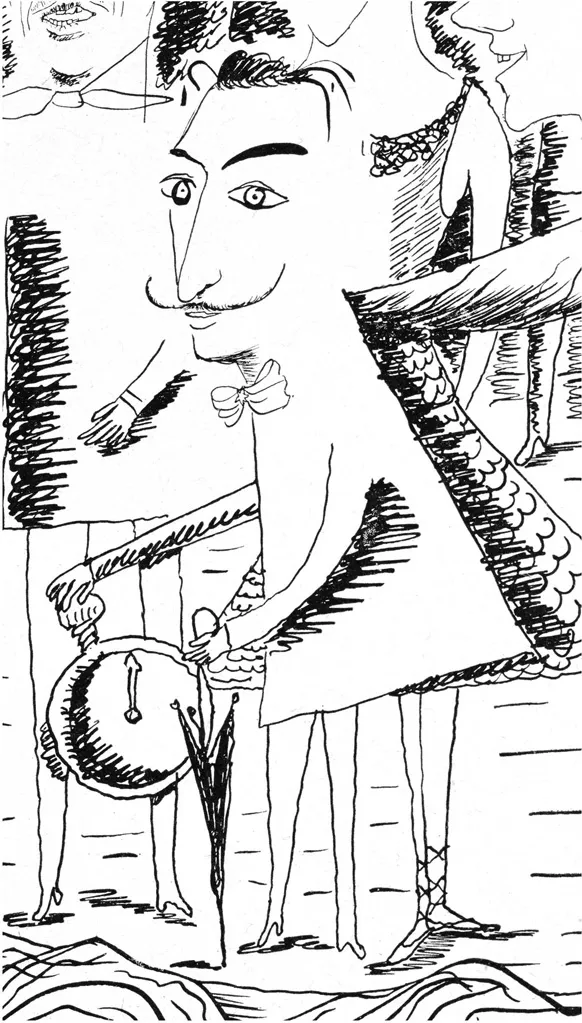

The surrealists always played for high stakes even when no money changed hands. In the spring of 1941, André Breton and several of his friends sought to flee Vichy France for the United States. Stuck in Marseille for several weeks while waiting for their visas to come through, they passed the time by inventing a version of the Tarot of Marseille, featuring the figures of the surrealist pantheon instead of the usual characters on the cards. The collective work comprised sixteen tarot cards drawn by Victor Brauner, André Breton, Oscar Domínguez, Max Ernst, Jacques Hérold, Wifredo Lam, Jacqueline Lamba, and André Masson. They were returning to the surrealist collective practices of the late 1920s, but also taking an ideological stand against racism—Wifredo Lam was of Chinese and Afro-Cuban descent—and for a world literature and art: “In order to keep the collective character of the group as anonymous as possible all these [drawings] have been faithfully redrawn by Delanglade” (Breton, “Le jeu de Marseille” 90). One of these images shows Lewis Carroll’s Alice (see Figure 1a), transformed into one of the playing cards she meets in Wonderland, becoming the Siren of the dream represented by the suit of the black star. We can juxtapose this surreal echo of Wonderland with a very different one from the pages of Vogue magazine a year later (see Figure 1b). There, Salvador Dalí appears in Vogue’s 1944 cartoon “Star-Packed Season” as the White Rabbit, fancily dressed in black tie, holding an umbrella and winding his watch (Peck 30).

The playing of games had been an essential surrealist practice. “Exquisite Corpse,” “One Inside the Other,” or reading the Tarot cards were “Delightful games for all ages;/Poetic games,” as Breton called them in his poem “The Mystery Corset.” When the surrealists invented their own Tarot game, they weren’t being particularly original. Lewis Carroll himself had devised “The Game of Alice in Wonderland” which was composed of 52 cards featuring his characters: Alice is the Queen of Hearts, transposed by the surrealists across the color spectrum from red to blue, with the red heart becoming the oxymoronic, oneiric black star. A central character is the White Rabbit, holding his watch and umbrella, just as Vogue would represent Dalí. The similarities between Carroll and Dalí go even deeper: long before Dalí started commercializing his art, Carroll was involved in promoting his books by licensing the production of biscuit tins and umbrellas bearing his Alice brand. A very surrealist act of history: the White Rabbit started as a fictional character, then became part of a game and came closer to life, only to become real with the apparition of Dalí, only to go back to the playful reality of cartoons in the pages of Vogue.

Figure 1a Wifredo Lam, Alice, sirène de rêve © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

Figure 1b Salvador Dalí by Priscilla Peck/Vogue © Condé Nast. “Star Packed Season,” Vogue, December 15, 1944: 30.

André Breton, surrealism’s would-be king (or errant White Knight), used to retire periodically to his childhood house in Lorient, Bretagne, the place where he grew up fascinated by the forests and by his grandfather Louis’ stories. Lorient was the land of dreams where Breton sought refuge whenever what turned out to be his existential project, the world as surrealism, seemed at a loss:

I myself shall continue living in my glass house where you can always see who comes to call, where everything hanging from the ceiling and on the walls stays where it is as if by magic, where I sleep nights in a glass bed, under glass sheets, where who I am will sooner or later appear etched by a diamond … The work of art, considered as being as seriously significant as such and such a fragment of human life, seems to me to be lacking in all value if it does not present the same hardness, rigidity, regularity and luster on all its surfaces, both inside and out, as the crystal … The house I live in, my life, my writings; I dream that these things appear from far away just like cubes of rock-salt seen at close range.

What is Surrealism? 40–41

Breton’s dreamy glass house—a complement to Carroll’s world imagined through the looking glass—is also a self-portrait, and a perfect example of what the surrealist object is: a transparent, non-utilitarian thing, a response to an inner necessity and desire. Unlike the opaque objects of adulthood, seen through a “river of sand,” the objects of childhood are transparent, and a glass house or a crystal opens a world without borders, in a process that Alice-Breton, following Max Ernst, calls dépaysement (Breton, La clé des champs 25). Throughout the history of the surrealist object, transparency appears in a number of contexts, such as the shop window where it brings a surreal world into our immediate reality like the Dalí-Duchamp window displays in New York, or Breton’s window display for the Gradiva art gallery that he opened in Paris. Even years later, it survives through a project like Orhan Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence in Istanbul, where his surrealist objects are shown in neatly arranged glass cases.

André Breton and Salvador Dalí are responsible for the two versions of surrealism that traveled worldwide; one refused to grow old in the practice of the game, as Pierre Bourdieu would say, and the other wanted to gain immediate consecration and transform the symbolic into social and economic capital, using both short-term and long-term strategies. Breton, the father of surrealism, remained in his surreal glass house described in Nadja and Amour fou, dreaming of a world where dreams can revolutionize poetry and solve the existential problems of mankind, as the first surrealist manifesto promised, refusing any compromise with the political and economic world. Salvador Dalí, the prodigy whom Breton brought from Cadaqués to revitalize the movement in 1929 by incorporating the visual arts, guarded Breton’s dream for a while, until he got bored with surrealism’s running against Time and decided that he should run after it. He set his watch to the Eastern Time Zone and moved his brand of surrealism to New York. Afraid of running late for his meeting with the New York socialites, the master of melted watches molded time into his own name when he published The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí with the anagrammatic Dial Press in 1942. What Breton feared most—growing old in the practice of art—Dalí turned into a strategy for the New York market. As he concludes in the “Epilogue” of this book of memoirs: “I have no desire to fight a duel with anyone or with anything; I want only two things: first, to love Gala, my wife; and second, that other inescapable thing, so difficult and so little desired—to grow old” (399).

Even as late as 1952, Breton would still advocate the surrealist position as if he was a newcomer to the game, constantly refusing any means of consecration and sticking to his initial credo throughout a lifetime. Alice-Breton could never accept that surrealism could grow old and become established in the field, commercially or even academically. The fact that surrealism was already being taught in some universities in 1951 made it suspect from Breton’s point of view:

In the word “place” there’s always the idea of official consecration involved, which disturbs me. I have already said that by temperament far more than by reason I always positioned myself in the opposition, I was ready to join, come what may, an endlessly renewable minority … In my opinion, it’s already too much that surrealism is taught in schools. I have no doubt that this will only reduce it.

Breton, Entretiens 217

Adrienne Monnier took a skeptical view of the surrealists’ Alice-inspired unconventionality, and in a letter she spoke ironically of “Lewis Carroll, whom the surrealists justly hail as one of their masters (doesn’t surrealism represent a counterpart of English ‘nonsense’?)” (The Very Rich Hours 182). In the same letter she made a perceptive remark about surrealism’s target audience: “This aggressive nonconformism is certainly what most seduces young people, very young people, who are still rallying to surrealism, which for them is mixed up with what has been called ‘the crisis of juvenile originality.’ It is the need to escape from family or school authority, the horror of social cogwheels, the desire to assert one’s personality. It is on a par with speaking Javanese” (181).

More positively, Monnier’s friend Valery Larbaud, whose name is inextricably bound to Joyce’s success in Paris, hailed the surrealist poets as Carroll’s rightful heirs. As he wrote to Monnier, Larbaud took pleasure in rubbing Breton’s poetry into the snobbish nose of “Mrs. Arnold Bennett,” as he ironically called the wife of the anti-modernist novelist: “It was the poem ‘Bohemia Crystal Vase’ by A. Breton. I responded to her request, after having briefly compared Dada and Lewis Carroll’s and Edwards Lear’s nonsense poetry. That put them at ease and showed them that France too has good ‘nonsense poets’ (between you and me, better than theirs, since the advent of Dada)” (Lettres 52). Monnier wasn’t impressed. She considered that surrealism was best suited for adolescents, and she strikes a very interesting note on the relation between age, the surrealist object, and cruelty, writing of “the cruelty of children, a cruelty that is generally manifested in actions and not in utterances; it is the physical object—whether animate or inanimate, it is an object because it is perceived as being nonrelated—that first of all provokes curiosity in children and then cruelty as a means of complete investigation” (Monnier 82).

Breton never wanted to become a central authority, or so he often claimed. When André Parinaud asked him if the series of their 1951 radio interviews revealed the “real André Breton,” Breton replied that he thought the purpose was to reveal surrealism, not himself: “From the first questions you asked me I was, of course, led to think that the object of these interviews was surrealism and not myself. Since I was invited to tell the chronological story of a spiritual adventure that was and remains collective, I had to somewhat efface myself from it” (Entretiens 213). At the end of...