![]()

Chapter 1

At the Intersect of Business and Higher Education: Historical, Theoretical, and Empirical Perspectives on Interorganizational Relationships

Morgan R. Clevenger and Cynthia J. Macgregor

Abstract

This interorganizational discussion covers Astley and van de Ven's (1983) Organizational Analysis Matrix and key information to understand a broader, macro discussion including the purpose of organizations in society as well as overview the interorganizational relationships between the for-profit sector (i.e., businesses and corporations) and the specific sector of higher education. A consideration of motives, return on investment expectations, and interorganizational behavior is explored. This chapter highlights the complex nature of higher education and the for-profit realm, including inconsistent third-party support and intermingling from the government. Highlights from Sethi's (1975) seminal article serves as the basis for measurement and future expectations in a three-state schema for classifying corporate behavior.

A market in which participants are driven by greed and desire to obtain momentary competitive advantage by any means—a market without trust, cooperation, compassion, and individual integrity—is not just an unpleasant place to do business. It is also highly inefficient…Neither a society nor a market economy can function efficiently without a moral foundation.

David Korten (2001, p. 96)

Helping people doesn't have to be an unsound financial strategy.

Melinda Gates (National Philanthropic Trust, 2018, 46)

1.1 Introduction

Historically, higher education and its agenda have been shaped by the communities that founded them (Duderstadt, 1999/2000). The community includes not only citizens but also for-profit and nonprofit partners as well as the various levels of governments. Varying views have endured on the purposes, merits, consequences, and realities that manifest in the relationship between US corporate America and higher education. Ostrander and Schervish (2002) argued that a two-way social relationship exists involving a social cause and financial backing of that cause; however, by-products or other tangible and intangible benefits exist and can be manipulated. Supporters, recipient organizations, and boards all play a role in such biased behavior (Carroll & Buchholtz, 2014; Haley, 1991; Ma & Parish, 2006).

Higher education institutions have had various reasons to be engaged with corporations (Ciconte & Jacob, 2009; Clevenger, 2014, 2019; Fischer, 2000; Fry, Keim, & Meiners, 1982; Gould, 2003; Pfeffer & Salancik, 2003; Rhodes, 2001; Saiia, 1999, 2001; Slaughter & Rhoades, 2004). Likewise, businesses and corporations historically had a variety of reasons for being corporate citizens (Carroll & Buchholtz, 2014; Cone, 2010a; Johnson, 1966; Saul, 2011). One key is that businesses have desired to support higher education. Examples include view of shareholder philanthropic support, managerial discretion and passion for social-related causes, ability to give from profitability and economic status, or board emphasis on charitable causes. Some motives have had “strings-attached” reasons such as return on investment; advertisements; relatively low-cost investments such as research, public relations, image, and social currency (Carroll & Buchholtz, 2014; Ciconte & Jacob, 2009; Clevenger, 2014, 2019; Fischer, 2000; Gould, 2003; Litan & Mitchell, 2011).

Since the 1950s, increasing attention has been directed by companies to be participatory and responsible citizens (Camilleri, 2017a). (See Bowen's (1953) seminal book Social Responsibility of the Businessman and Farmer and Hogue's (1973) book Corporate Social Responsibility.) A range of goals and purposes have ensued around the topic of business engagement. Specifically, much controversy, accountability, and edification continue to create attention to interorganizational relationships by companies – particularly with higher education (Camilleri, 2017b; Carroll, 1979, 1998; Crane & Matten, 2004; Freeman, 1984; Matten & Crane, 2005; Porter & Kramer, 2006, 2011; Visser, 2011, 2014; Waddock, 2004).

American higher education and U.S. corporations are uniquely intertwined, and the dynamics between them have been described by several prominent authors. “Inter-organizational relations, as its subject name suggests, is concerned with relationships between and among organizations” (Cropper, Ebers, Huxham, & Ring, 2008, p. 4). An interorganizational relationship “is concerned with understanding the character, pattern, origins, rationale, and consequences of such relationships” (Cropper et al., 2008, p. 4). “Inter-organizational relationships are subject to inherent development dynamics” (Ebers, 1999, p. 31). Four development dynamics include “the parties' motives,…the pre-conditions and contingencies of forming inter-organizational relationships,…the content, and…the outcomes” (Ebers, 1999, p. 31). Similarly, Aldrich (1979) indicated four dimensional considerations of formalization, intensity, reciprocity, and standardization of reoccurring behavior. Beyond these factors, organizations constantly learn how to act and to react to other organizations (Aldrich, 1979; Ebers, 1999; Guetzkow, 1966; Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Pfeffer & Salancik, 2003). The three processes for organizational learning and respective interorganizational engagement include understanding, revaluation, and adjustment (Ebers, 1999; Ring & Van de Ven, 1994). Ebers described interorganizational learning as follows:

In the course of an ongoing inter-organizational relationship, the parties may for instance learn more about the environmental challenges and opportunities that affect the contents and outcomes of their relationship; they may learn more about one another, for example, about their goals, capabilities, or trustworthiness; and they may learn how they could perhaps better design their relationship in order to achieve desired outcomes. (p. 38)

These contextual factors push interorganizational relationships “to evolve over time” (Ebers, 1999, p. 38). “Over time, the interactions among organizations become institutionalized” through routine, formal associations, and frequent interactions (Guetzkow, 1966, p. 24).

Attention to private support for higher education continues to increase as government dollars decrease. Most research in financial support and engagement of higher education institutions has been atheoretical and offers guidance only for practitioners (Caboni & Proper, 2007; Clevenger, 2014; Drezner, 2011; Kelly, 1998; Young & Burlingame, 1996). Higher education has contributed greatly to society. Cohen (2010) said, the Carnegie Commission translated the traditional purposes of higher education – teaching, research, and service – into five sets of goals: (1) providing opportunities for the intellectual, aesthetic, ethical, and skill development of individual students; (2) advancing human capability in society at large; (3) enlarging educational justice; (4) transmitting and advancing learning; and (5) critically evaluating society for the sake of society's self-renewal (p. 278). As a pluralistic society, higher education, the state and federal governments, and corporations were all rallying behind quality, accessible education. A major shift occurred in the 1970s as US corporations became larger global entities. The corporations began embracing their engagement and charitable involvement with higher education and nonprofits as a strategic action (Cone, 2010a; Sheldon, 2000).

Additionally, corporations became more comfortable with their societal relationships to openly reveal their processes, to create extensive annual reports, and to promote their social contributions to society (Cummings, 1991; Lydenberg & Wood, 2010). Higher education and other community stakeholders “rely on information from annual reports, rating agencies, news releases, magazine articles, websites, blogs, and corporate social reports” to be aware of, to understand, and to act or react to corporate motives and behaviors (Clevenger, 2014; Greenberg, McKone-Sweet, & Wilson, 2011, p. 115). A corporation's annual reports may also be labeled as “social report, public interest report, values report, integrated report, ethics report, integrity report, sustainability report, or triple bottom line report” (Kaptein, 2007, p. 71). Regardless of name, such reports and other information “portray the relationship between a corporation and society” (Lydenberg & Wood, 2010, p. i). Such reporting adds credibility to the perspectives of corporate accountability and communication, environmental, financial, human rights, and social concerns (Greenberg et al., 2011; Kaptein, 2007; Lydenberg & Wood, 2010). Such reports often include perspectives of stakeholders as well as endorsement of certain codes of behavior (Lydenberg & Wood, 2010).

This chapter begins the discussion of interorganizational relationships in the field of organizational analysis to explore and discuss the space between higher education and business. This chapter explores the pluralism of the United States, interorganizational dynamics and pressures, and trends in the late twentieth century and the new millennium. Finally, the chapter illustrates the disparate scholarly research that has begun to take shape to promote attention to these relationships and to create an opportunity for further research.

1.2 What Has Been and Is Happening

The United States, a pluralistic society, consists of a multitude of groups and organizations that coexist to provide diffusion of power among them, wide decentralization, and diversity (Carroll & Buchholtz, 2014; Eisenstadt, 1981; Jacoby, 1973; Morgan, 2006). Virtues of a pluralistic society include preventing power from being concentrated in the hands of a few, maximizing freedom of expression and balance, minimizing the danger of any one leader or organization being in control, and providing built-in checks and balances. America's pluralistic environment requires all parties to take interest, ownership, and responsibility for rational behavior and joint ownership for social values (Jacoby, 1973; Saul, 2011).

1.2.1 Pluralistic Intersection

In our pluralistic society, three entities that interface on behalf of society are the state and US governments, higher education, and corporations. Restated, these three sectors are often labeled: the state, nonprofit, and for-profit. First, the state and federal governments exist to give structure to societal functioning, including laws and ethical expectations. Public higher education is an extension of state governments. Second, the nonprofit sector – which includes private higher education – exists to foster the development of individuals, to prepare individuals for careers and life work, and to sustain a quality life well-being through a myriad of special purposes including health, community, art, religion, animal welfare, and the environment. Specifically, “education provides a foundation for personal growth, professional training, and social mobility” (Rhodes, 2001, p. 9). Both public and private higher education are also expected to contribute in a myriad of ways to society via science, medicine, art, humanity, business, and many other disciplines to improve and to enlighten the world (Bush, 1945; Gould, 2003). Higher education seeks to advance public or societal goals (Fulton & Blau, 2005). Additionally:

The American system of higher education is acknowledged as the finest in the world and our colleges and universities have been essential to our success as a nation. Now we are living in a new world economy, one that emphasizes ideas over products and the life of the mind over work with the hands. In this environment, higher education is more central than ever to the economic and social progress of all nations. (Worth, 2002, p. 298)

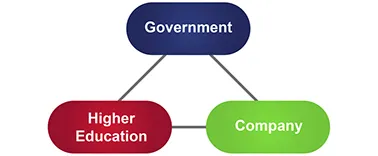

Finally, the for-profit sector, known as businesses or corporate America, serves as the economic cornerstone of the US capitalistic economy in a democratic republic (Carroll & Buchholtz, 2014; Drucker, 1946; Gould, 2003). Sábato's Triangle (see Fig. 1.1), developed in 1968, illustrates this dynamic relationship and the joint ownership these entities have in society (Hatakeyama & Ruppel, 2004). Civil society, the government, and the market intertwine social, political, and economic interests to create the interplay of exchanges operating countries (Waddell, 2016).

Fig. 1.1. Adaptation of Sábato's Triangle. Note: This graphic was developed in 1968 by Jorge Sábato and Natalio Botana, and illustrates the relationship among government, US businesses (labeled Company), and the private sector, such as higher education, as labeled here. The team’s thinking was considered “advanced for the time” (Hatakeyama & Ruppel, 2004, p. 2).

Corporations and higher education rely upon each other in an interorganizational relationship for mutual benefit (Carroll & Buchholtz, 2014; Gould, 2003; Liebman, 1984; Norris, 1984; Pfeffer & Salancik, 2003; Tromble, 1998). For example, higher education institutions yield professionals needed for hire in corporations as well as develop methodologies and make scientific discoveries that are to be transferred to society (Boyd & Halfond, 1990; Elliott, 2006; Gould, 2003; Just & Hoffman, 2009; Etzkowitz, Webster, & Healey, 1998; Slaughter & Leslie, 1997; Slaughter & Rhoades, 2004; Withers, 2002). However, “in any relationship where one partner has resources and the other seeks access to the resources, a power dynamic is created” (The Center on Philanthropy, 2007, p. 1). Giroux and Giroux (2004) and Sommerville (2009) argued that the past century of higher education has been stripped of its voice and leadership in America because higher education is also corporatized. Siegel (2007) contended that too many academicians and administrators operate on fear instead of information, communication, and close relationships with corporate representatives to create win-win situations for higher education and corporate interests. “The interests and concerns of academic and commercial enterprise increasingly overlap” (Siegel, 2012, p. 30). Johnson (2006a) summarized:

It's somewhat ironic that while recent infrastructure developments have enabled us to collaborate and engage with each other more easily than at any other time in history, changes in our thinking, attitudes, beliefs, and motivations have simultaneously placed obstacles in our way that have to be overcome. (p. 212)

A combination of resource dependence, societal expectations, and accountability create pressures on these complex interactions between and among interorganizational functioning.

1.2.2 Fiscal Intersection

One highly visible aspect of interaction between higher education institutions and corporations is financial (Eddy, 2010; Fischer, 2000; Gould, 2003; Rhodes, 2001; Solórzano, 2017). Higher education is funded by tuition, government aid, and private support, which includes individuals, foundations, and corporations. As governments cut funding, more of a burden falls on the private sector to help fund higher education purposes and goals (Arulampalam & Stoneman, 1995; Carroll & Buchholtz, 2014; Ciconte & Jacob, 2009; Curti & Nash, 1965; DeAngelo & Cohen, 2000; Drezner, 2011; Gould, 2003; Johnson, 2006; Levy, 2001; Rhodes, 2001; Shannon, 1991). Several factors contribute to the rising costs of higher education; these have created financial challenges: technology expense and implementation; the processing of labor intensity to educate students holistically, which comes with a price tag of professionals' costs; new programs to meet current world demands; and opportunity costs of inclusivity for all people to have access (Rhodes, 2001). Corporations have a significant financial impact on higher education through charitable contributions, which constitute a 10-year aggregated average of 15.52% of all funding dollars contributed and nearly 10% of higher education budgets (Kaplan, 2018).

“We need to be concerned about letting corporations dictate our social values, but this is not likely to happen” (Saul, 2011, p. 184). Saul indicated that organizations such as higher education institutions should help to set social agendas and then to create value propositions for funding partners such as corporations. Additionally, Saul explained that corporations are defined as “impact buyers” (p. 184). Funding from corporations often comes with clearly defined expectations and limitations (Fischer, 2000; Giroux & Giroux, 2004; Molnar, 2002). Debate about whether higher education institutions should receive corporate funding continues with varying viewpoints. “Companies seldom give resources out of altruistic motivations. Support for higher education is a strategic investment” (Sanzone, 2000, p. 321). “When a corporation funds charitable activities, it may do so with money that would otherwise be paid as taxes on profits…it often chooses projects with an eye to the good name or long-term interests” (Rhodes, 2001, p. 144). Note, however, that motivations and ethical behaviors have also been a concern of higher education institutions because of some dishonest solicitation, donor manipulation, and institutional mission abandonment, among other factors cited in Caboni's (2010) quantitative book of 1,047 fundraisers' behavior in American colleges and universities.

Creating positive, productive relationships requires win-win solutions for both parties (Bruch & Walter, 2005; Carroll & Buchholtz, 2014; Eddy, 2010; Levy, 2001; Siegel, 2012). Bolman and Deal (2017) indicated that the responsibility of organizational leaders is not to answer every question or to get every decision right but, rather, to be role models and catalysts for values – including ethical behavior – in all activities. When corporate self-regulation fails, government and society push for stronger legal and regulatory measures. Solomon (1993) called for deeper Aristotelian ethics, which include “honesty, dependability, courage, loyalty, integrity” (p. 105). Bolman and Deal observed that successful corporations engrain virtue and ethics into their corporate character. On the higher education side of the relationship, the Association of Fundraising Professionals (AFP) and the Council for Advancement and Support of Education (CASE) have promoted self-regulation to ensure ethical behavior of fundraisers and of higher education leaders (AFP, 2018; CASE, 2018).

1.2.3 Late Twentieth-century Trends

The last quarter of the ...